I’ve written before about how difficult I’ve been finding it to listen to much music these anechoic coronavirus days. My recordings aren’t doing it for me; the livestream efforts I check out, however admirable, leave me cold; I sadly and inexplicably want to punch all the cheerful radio hosts I hear right in the nose. (sorry Tom, Julie, Paulo, Mark, Alexa, Kathleen, Mike and Jean and whoever else I’ve offended)

I’ve written before about how difficult I’ve been finding it to listen to much music these anechoic coronavirus days. My recordings aren’t doing it for me; the livestream efforts I check out, however admirable, leave me cold; I sadly and inexplicably want to punch all the cheerful radio hosts I hear right in the nose. (sorry Tom, Julie, Paulo, Mark, Alexa, Kathleen, Mike and Jean and whoever else I’ve offended)

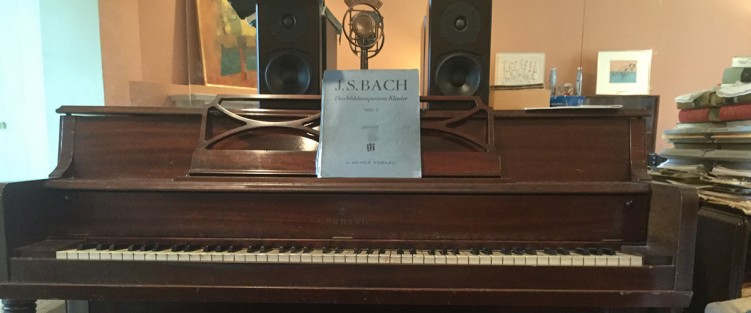

So I’m not listening much these days, but, lo and behold, much to my surprise I find that I’m playing more – a lot more, actually. I’m a pianist – well, OK, I play the piano, to be more accurate; there’s a difference, and I’m on the spectator side of the difference. I’m strictly an amateur player. I got my Grade 10 from the Royal Conservatory in my teens, and studied piano for my three years in the Music Department at the University of Ottawa, but never had the discipline, or nerves, or the temperament to be a professional player. Nonetheless, I make some music virtually every day one way or another and am still playing the Gerhard upright my parents bought me when I was nine. It’s been a daily part of my life for over 60 years now – the same instrument – maybe my closest companion. I can tell you where every scrape, scratch, discolouration from partying drinks inadvertently left on its surface, gouges and broken pedals came from (the move up and down the three flights of stairs in the house in which we had an apartment in Peterborough, with just my wife and I doing the hauling, was especially memorable). Next to my wife, daughter and dogs, my piano is the closest thing to me that I know. I really don’t know how I could live without it.

As I say, I probably have spent some time at that Gerhard virtually every day since I was a kid. However, in these silent pandemic days, when other music-making has been stilled, my playing for myself has taken on a new vitality. I’m not just noodling through and sight-reading the various pieces of music that have accumulated over the years in my personal playing library, I’m actually sitting down diligently and trying to learn them thoroughly and completely and play them with something approaching a real artistic polish. Or the best I can muster. Maybe for the first time in my life, I’m really seriously practising.

The range of pieces I play is hilarious to me, sort of an archeological dig through my musical life story. There’s the Grieg concerto, that an optimistic teacher had me try and learn when I was 13. There’s the Scriabin Étude Op.2. No.1, which I photocopied from the U of T library and pasted onto one of my Dad’s shirt cardboards after hearing it played as an encore on Horowitz’s Return to Carnegie Hall disc in 1965. A piano solo arrangement of Rhapsody in Blue that still has my name and old phone number written neatly in a childish hand on the inside front cover. These days I’m focusing on an eclectic range of repertoire: the Bach prelude and fugue from Book 1 of the WTC – No.5 in D Major, that I studied in university; the Gershwin piano concerto; Schubert’s E-flat Major impromptu; Schumann’s Des Abends and his astonishing Op.28 F-sharp Major Romance; the first Brahms concerto; Schoenberg’s Five Piano Pieces Op.19. And so on.

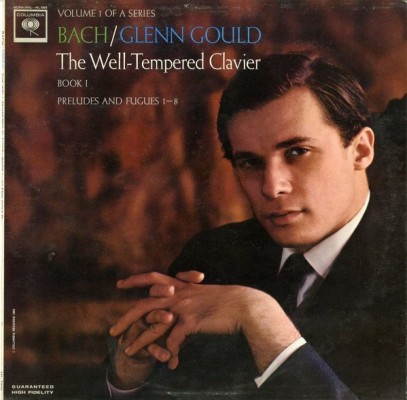

And, as I play, new insights about music and performance have been flooding over me. Especially when I compare my renewed efforts to the professionals beckoning to me from YouTube. I know you’re not supposed to do that, but how can you avoid it? But, as I do, I am struck, not quite for the first time, but close, by how important the physicality of music-making is. Not the phrasing, or tone, but the sheer physical presence of a performance. The way your fingers or hands actually touch the keys and connect to the sound they coax out of the instrument. Hardly a gloriously original revelation, but important for me. And telling. For instance, I’ve been playing, or trying to play, that D-Major prelude from Book 1 of the WTC for many years, decades actually – and I’ve always been alternately fascinated and alienated by Glenn Gould’s performance of it, at a ridiculously quick tempo.

This summer, I decided to try to practise enough to finally match his speed – I’m still not quite there, the piece demands a strength in the fourth and fifth fingers of the right hand which I don’t yet have (and may never develop), but I’m getting close, much to my delight and surprise. However, what I’ve discovered, equally to my surprise, is that I find absolutely no satisfaction playing the piece at that tempo, even when I can. This I find fascinating, because I love listening to Gould play it at that tempo. I have come to realize that my interpretations of pieces of music are very much tied to my physicality; not just my technical strengths and weaknesses, not just my abilities and limitations, but beyond that, something innate about the way my mind and body are connected, something I can’t really understand or explain. But something really important. And I wonder if this is true of all players, even the most professional.

This summer, I decided to try to practise enough to finally match his speed – I’m still not quite there, the piece demands a strength in the fourth and fifth fingers of the right hand which I don’t yet have (and may never develop), but I’m getting close, much to my delight and surprise. However, what I’ve discovered, equally to my surprise, is that I find absolutely no satisfaction playing the piece at that tempo, even when I can. This I find fascinating, because I love listening to Gould play it at that tempo. I have come to realize that my interpretations of pieces of music are very much tied to my physicality; not just my technical strengths and weaknesses, not just my abilities and limitations, but beyond that, something innate about the way my mind and body are connected, something I can’t really understand or explain. But something really important. And I wonder if this is true of all players, even the most professional.

We have this ideal, or myth, that being a professional player means having worked hard enough to make technical barriers disappear in music-making, so that a musical interpretation can flow directly from mind and soul to sonic realization without any of those pesky physical bugaboos getting in the way. It’s almost as though we work as hard as we can in music to make the body, in effect, disappear, cease to be, so that only the pure mind and spirit can find realization in the music. I’m now beginning to wonder if that is true, or even should be an ideal.

I ask this question because I’ve been re-reading a famous article from about 15 years ago by musicologist Carolyn Abbate called “Music – Drastic or Gnostic” based on her studies of French philosopher Vladimir Jankélévitch’s theories of music. Jankélévitch and Abbate are convinced that we in the West have seriously underestimated the value of the physical and the immediate in music-making (the “drastic” or event-based) and consequently overvalued the intellectual (the “Gnostic” or knowledge-based). To them, music-making is only and can only be an immediate, this-moment, intensely physical experience, even when we appreciate it only as listeners. They are convinced we have robbed music of much of its power by failing to sufficiently understand or honour this brute, bodily, sensual physicality of the music-making experience.

And not only do I find a new appreciation of Abbate’s polemics (as I sit at my keyboard trying to get the damn contrary-motion section at the end of my Bach prelude to work properly, realizing that part of the beauty of the music lies in the sheer physical sensations allied with playing it), I’m beginning to wonder if she hasn’t put her finger on exactly what we have been missing in the absence of live music-making these days. It’s not the community aspect; it’s not the exuberant enjoyment of the sonic pleasures of a live hall, impossible to duplicate no matter how excellent a recording. It’s that physicality of music, witnessing that raw, immediate sensual human energy that is not incidental to music-making, or a barrier to be overcome in it, but the heart of what the communicative potential of music is all about.

That’s why our musical sensibility seems so starved today; we’re missing the touch of music (the “grain” Roland Barthes once famously called it), which we need as much as, if not even more than, the sound. If Abatte is right – and as I sit on my piano bench with my Bach prelude beckoning me, tantalizing me from the music stand, I think she might be – we may have learned something very important in these sequestered days, something we should remember when the air has cleared and we can breathe freely again.

That’s why our musical sensibility seems so starved today; we’re missing the touch of music (the “grain” Roland Barthes once famously called it), which we need as much as, if not even more than, the sound. If Abatte is right – and as I sit on my piano bench with my Bach prelude beckoning me, tantalizing me from the music stand, I think she might be – we may have learned something very important in these sequestered days, something we should remember when the air has cleared and we can breathe freely again.

If we can recall, when this is over, exactly what we were missing when we lost our music, we will find ourselves in touch with it all the more vividly when it is returned to us.

Robert Harris is a writer and broadcaster on music in all its forms. He is the former classical music critic of the Globe and Mail and the author of the Stratford Lectures and Song of a Nation: The Untold Story of O Canada.