Music and the Movies: I Am the Blues

Daniel Cross, the writer and director of the lively new documentary, I Am the Blues, believes that the blues is the root of all music. “It’s about the first-person lived experience,” he said after the film had its Canadian premiere at the recent Hot Docs film festival. At 18, he had his own experience with bluesmen when he went on a vodka run at a blues festival on the West Coast and returned with his bounty and was welcomed with open arms by a number of legendary musicians.

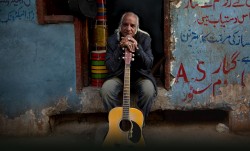

Now, more than three decades later, his mission to record the last of the original blues devils still working the Chitlin’ Circuit has born fruit with this joyful testament. The film is a musical journey through the swamps of the Louisiana Bayou, the juke joints of the Mississippi Delta and the moonshine-soaked BBQs in the North Mississippi Hill Country. Several octogenarians act as guides on the journey, telling the stories behind the songs and jamming on a front porch. Bobby Rush, 80ish, gets his inspiration these days while driving his car on the back roads; at seven, while he was picking cotton, he passed the time imagining himself on stage with Muddy Waters or Cab Calloway. In Chicago in the 1950s, he played behind a curtain -- white customers didn’t want to see the faces of black musicians.

Lil’ Buck Sinegal, the “Master of the Stratocaster,” plays an electric blues riff as a crawfish boil is cooking. “The blues made me and I’m making blues now,” he says before talking shop with Blues Hall of Fame member and master of the harmonica, Lazy Lester, while picking crawfish out of the bowl. Barbara Lynn, a youngster in her mid-70s joins Bobby Rush and Lester in an impromptu Stagger Lee that jumps with life. There’s a memorable moment with L.C. Ulmer just months before his death. Soul blues diva Carol Fran shows her stuff. Making music nourishes their spirit.

Jimmy “Duck” Holmes, the proud owner and operator of the legendary Blue Front Cafe, the centre of musical life in Bentonia, Mississippi, has carried on the business his parents opened the year after he was born in 1948. Bud Spires, another mouth harp virtuoso learned from his father from the age of five. That is how the blues survived. I Am the Blues wonders if the tradition can regenerate, even as the film presents a great case for those who carry it on and Skip James, Bentonia’s most famous son, belts out Crow Jane as the credits roll.

I Am the Blues plays a limited engagement at the Bloor Hot Docs Cinema, June 3 to 9. Held over at the Bloor, it expands to Cineplex Canada Square and the Kingsway Theatre beginning June 10.