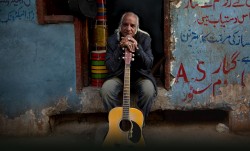

Najaf Ali and his father, Rafiq Ahmed, are drummers in Lahore, for a thousand years the centre of music in Pakistan. Like many musicians there, Najaf learned to play in childhood under the tutelage of his father. A coup by General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq in 1977 led to the installation of Sharia law and the banning of music throughout the country. A rich musical tradition was suddenly cut off from its audience. By the time the restrictions had eased, there was a serious disconnect with the general population and much of the younger generation knew nothing of the music at all.

In 2004, Izzat Majeed founded Sachal Studios to provide a place for traditional music in a nation that had rejected its musical roots. After convincing a number of master musicians to pick up their instruments again, some classical and folk recordings were released with little fanfare. But it was an experimental album fusing jazz and South Asian instruments brought them worldwide acclaim. Their version of Dave Brubeck’s classic, Take Five, rode the Internet all the way to Wynton Marsalis, artistic director of Jazz at Lincoln Center. And Brubeck himself said: “This is the most interesting recording of Take Five that I’ve ever heard.” (Majeed had fallen for jazz as a schoolboy when he heard Dizzy Gillespie, Duke Ellington and Dave Brubeck live in Lahore as part of the U.S. State Department’s Cultural Ambassadors program.)

Song of Lahore, the new documentary co-directed by Andy Schocken and Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy (who conceived it), begins smartly by focusing on the family connections among the members of the Sachal Jazz Ensemble (SJE), tracing their love of music and its roots while contextualizing their plight within the political and social history of Pakistan. Obaid-Chinoy, a double Oscar winner in the Short Documentary Film category -- including this year’s film about honour killings, A Girl in the River: The Price of Forgiveness -- is a socially conscious filmmaker with a journalistic background, who credits her time in Toronto from 2004 to 2015 with honing her craft.

Midway through this straightforward and informative documentary, Song of Lahore takes flight (literally and figuratively) when the SJE is invited by Marsalis to join him and the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra (JALCO) for a concert in New York City. The energy and freedom of Manhattan liberate the visitors but it’s during the rehearsals for the concert that the real charm of the film takes hold.

The implacable rhythmic foundation of the three drummers is a natural fit with Marsalis’ horn-heavy orchestra (“You start,” Marsalis says to them. “We need you to set the groove up.”). There is some drama: East and West must find avenues of communication; a misfiring sitar player is replaced by a local New Yorker. But the climactic footage of Take Five, Jelly Roll Morton’s New Orleans Blues and Ellington’s Limbo Jazz the next evening in the concert elevate the film to a higher plane. Baqar Abbas’ flute -- we saw him early in the film carving out a new instrument by hand and drilling it with perfectly placed holes -- can more than hold its own in a thrilling dialogue with JALCO’s flutist. Ballu Khan’s breathtaking tabla solos in New Orleans Blues are a standout. “When people are soulful and want to come together, then they do,” Marsalis says.

Rafiq Ahmed Bauji. Marsalis smiles as he repeats the name, delighting in its musicality. The musicality of Rafiq Ahmed’s dhol playing would later delight the Lincoln Center audience; as would Najat Ali’s naal.

Song of Lahore plays at the Bloor Hot Docs Cinema March 4 to 10.