Music and the Movies:National Canadian Film Day 150

![]()

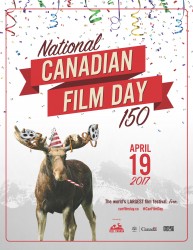

Oui The North. On April 19, 340 unique feature films will screen for free in more than 1700 locations in Canada, plus over 60 international sites like Canadian embassies and Canadian military bases, to celebrate our country’s movies in this sesquicentennial year. From 90 screenings in Toronto to two in far-flung Tuktoyaktuk NT (appropriately The Sun at Midnight and The Lesser Blessed), the country will be blanketed in movies from coast to coast to coast in what is billed as the world’s largest film festival. “Everything from high to low,” Reel Canada’s artistic director Sharon Corder told me mid-March.

Oui The North. On April 19, 340 unique feature films will screen for free in more than 1700 locations in Canada, plus over 60 international sites like Canadian embassies and Canadian military bases, to celebrate our country’s movies in this sesquicentennial year. From 90 screenings in Toronto to two in far-flung Tuktoyaktuk NT (appropriately The Sun at Midnight and The Lesser Blessed), the country will be blanketed in movies from coast to coast to coast in what is billed as the world’s largest film festival. “Everything from high to low,” Reel Canada’s artistic director Sharon Corder told me mid-March.

Reel Canada has been moving towards this unique celebration since they began showing Canadian films in schools in 2005. The inaugural Canadian Film Day, April 29, 2014, became an annual event that will culminate April 19 with this year’s National Canadian Film Day 150 (in partnership with the Toronto International Film Festival’s Canada On Screen project which is responsible for 150 of the screenings).

“In scale and intention,” Corder said. “We’ve been building to this. We’re going after everyone.” What an extravaganza it will be, a far cry from the not-too-distant past when Canadian movies (English-language in particular) were scorned by the general public. Now the richness of our film culture is evident from Oscar nominees to Cannes prizewinners. And, as Corder points out, because of the school webcast (with schools screening films before logging on to interact with guests), movies like Breakaway and The Trotsky are two of Reel Canada’s most popular. The same goes for the French school webcasts and Paul à Québec. And because of the “respectful inclusion of Indigenous people,” there will be more than 75 screenings of films by Indigenous filmmakers.

Some of the most popular films being screened April 19 are:

The Grand Seduction, Snowtime/La guerre des tuques, Passchendaele,

La légende de Sarila (The Legend of Sarila), The Whale, Corner Gas: The Movie, The Rocket, Anne of Green Gables, The Sweet Hereafter, Angry Inuk, Stories We Tell, Water and Sharkwater.

“Not necessarily what anyone could predict, eh?,” Corder said.

And then there the films that fit nicely into The WholeNote’s Music and the Movies niche. Most, if not all, can be seen somewhere in Canada on April 19.

What follows is a random sampling of films where music plays a significant role headed by the most recent.

Xavier Dolan’s emotionally riven chamber piece, It’s Only the End of the World (2016), won six Canadian Screen Awards, three French Césars and the Grand Prix at Cannes. Dolan’s camera lingers on his characters in close-up, accentuating pauses, building to the affective climax. Gabriel Yared’s warm, empathetic symphonic score and pop music outbursts like Camille’s Home Is Where It Hurts, Grimes’ Oblivion and the Moldovan pop group O-Zone’s Dragostea Din Tei are crucial ingredients.

Toy Piano Composers co-founder Chris Thornborrow wrote the evocative score to director Andrew Cividino’s Sleeping Giant (2015), which captures the energy of growing up near Lake Superior in a well-crafted character study over one summer of awkward adolescence. Kevin Turcotte’s uncanny trumpet on the soundtrack of Robert Budreau’s Born To Be Blue (2015), a reimagining of Chet Baker’s life, is essential to making Ethan Hawke’s portrayal of Baker believable. Pianist David Braid, who arranged the extensive music track (which is far more reality-based than the plot), leads the fine quartet of Turcotte, bassist Steve Wallace and drummer Terry Clarke.

Stéphane Lafleur’s understated little bijou, Tu Dors Nicole (2014) filmed in rich black and white, is a finely etched portrait of a 22-year-old young woman maturing over one aimless summer. Xavier Dolan’s Cannes prizewinner, Mommy (2014), which jumps off the screen with a life force that is contagious, is driven by a carefully chosen soundtrack of music performed by Sarah McLachlan, Dido, Counting Crows, Andrea Bocelli, Lana Del Rey and the ecstatic use of Oasis’ Wonderwall.

Gabrielle, the title character of Louise Archambault’s exceptional Gabrielle (2013), is a young woman with Williams syndrome (a genetic condition characterized by learning disabilities, among other medical problems). She has a contagious joie de vivre and perfect pitch (exceptional musical gifts are a positive blessing of Williams syndrome). Gabrielle and her boyfriend are members of a choir that is preparing for an important music festival. The film’s emotional impact is unforced and uplifting.

In his mesmerizing documentary, The End of Time (2012), Toronto filmmaker Peter Mettler uses images and sound -- the tools he’s most comfortable with – to observe time and make our experience of it palpable. Music by Autechre, Robert Henke and Thomas Koner animates his images (of lava flowing on the big island of Hawaii, for example) while techno DJ Richie Hawtin (“Plastikman”) distills time down to its basic rhythm and Christos Hatzis’ and Bruno DeGazio’s Harmonia depicts harmonic overtones.

Nathan Morlando’s cinematic intelligence permeates every frame of his film debut, Edwin Boyd: Citizen Gangster (which won Best Canadian First Feature at TIFF 2011). His cinematic good sense led him to hire Max Richter to compose the music which supported the narrative without ever being overbearing.

The following classics of Canadian cinema are inseparable from their musical bearings:

I am one of many who believe Zacharias Kunuk’s Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner (2001) is the best Canadian film ever made. Music by Huun-Huur-Tu, Christopher Mad'dene, traditional Inuit ajaja songs and throat singing, plus Chris Crilly’s score back this Inuit tale handed down over the generations. A masterpiece of stunning landscapes, epic in scope.

Francis Mankiewicz’s haunting Les Bons Débarras (1979) uses Mozart’s Piano Concerto No.23 K488, Franck’s Symphonic Variations and Puccini’s O mio babbino caro to underline its Gothic passion. The music in Jean-Marc Vallée’s coming-of-age masterpiece, C.R.A.Z.Y. (2005), is inseparable from its narrative. Patsy Cline, Charles Aznavour, Grace Slick, Pink Floyd, David Bowie and the Rolling Stones (among others) form the soundtrack to a life. And Perez Prado’s Mambo Jambo makes it alright in the end.

Denys Arcand’s Le Déclin de l'empire américain (1986) captures a vibrant historic moment in Quebec’s intellectual and social history to a score by François Dompierre. Arcand’s next film, Jésus de Montréal (1989), uses Pergolesi’s Stabat Mater and the exotic The Mystery of Bulgarian Voices to buttress his engrossing, uncompromising look at contemporary religious values.

Bruce McDonald’s iconic road movie, Highway 61(1991) is propelled by The Archies, Bachman-Turner Overdrive, Tom Jones, The Ramones, Sonny Terry, Nash the Slash, The Razorbacks, Rita Chiarelli, Colin Linden and the infamous Bourbon Tabernacle Choir.

Alan Zweig will make a guest appearance April 19 at 9pm when his compulsive documentary, Vinyl (2000), shows (appropriately) at the Sonic Boom Cinema Club, 215 Spadina Ave.

One of the first Canadian films to make an international splash, Jean Beaudin’s J. A. Martin, photographe (1977), a beautiful cinematic portrait of a bygone age, is supported by Maurice Blackburn’s unobtrusive score.

Oscar winner Howard Shore has worked with David Cronenberg on almost all his films including the seminal Scanners (1981), Videodrome (1983), Dead Ringers (1988) and Crash (1996).

Mychael Danna, another Oscar winner, has scored almost all of Atom Egoyan’s films including the still-resonant The Sweet Hereafter (1997). He has an uncanny but totally unforced ability to combine Western and non-Western music seamlessly. For proof, watch (and listen to) Deepa Mehta’s best film, Water (2005).

Egoyan’s Calendar (1993), unusual in not being scored by Danna, is one of the director’s most revealing and personal films. The music by Eve Egoyan (piano), Jivan Gasparyan (duduk), Hovhanness Tarpinian (tar) and Garo Tchaliguian (singer) reinforces the enigma that drives the film’s deceptive narrative.

Two indelible Music and the Movies moments: Atom Egoyan’s Exotica resonant with Leonard Cohen’s Everybody Knows and Sheila McCarthy literally flying high accompanied by The Flower Duet from Delibes’ Lakmé in Patricia Rozema’s I’ve Heard the Mermaids Singing (1987).

One film I wish was available: Julian Roffman’s beatnik time capsule, The Bloody Brood (1959), was Peter Falk’s first starring role and the movie that preceded Roffman’s widely heralded 3-D horror film, The Mask (1961). I saw it at a special TIFF Cinematheque screening several years ago and was delighted to see that the jazz combo that provided the music in the coffee house where Falk and his cohorts hung out was led by none other than the eternal hipster Harry Freedman. On English horn. How cool is that!

Finally, there is François Girard’s Thirty Two Short Films About Glenn Gould (1993), its elegantly constructed vignettes a masterful distillation of the life of a (musical) genius. That is the film I would choose to watch on National Canadian Film Day 150. Luckily for me, it’s showing at TIFF Bell Lightbox on April 19. Writer-actor Don McKellar and star Colm Feore are special guests.