Toast to the Danish

![]()

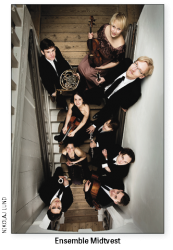

The youthful and adventurous Danish Ensemble Midtvest (EMV) makes its Canadian debut, March 13, as part of Mooredale Concerts’ current season. Mooredale’s artistic director, cellist Adrian Fung told me via email how he first met the group: “My Afiara Quartet tours Denmark every two years, each time playing over 20 cities. It was on one of these trips that I met the EMV, which is managed by the same energetic gentleman (Oliver Quast) who builds our successful Danish tours.”

The youthful and adventurous Danish Ensemble Midtvest (EMV) makes its Canadian debut, March 13, as part of Mooredale Concerts’ current season. Mooredale’s artistic director, cellist Adrian Fung told me via email how he first met the group: “My Afiara Quartet tours Denmark every two years, each time playing over 20 cities. It was on one of these trips that I met the EMV, which is managed by the same energetic gentleman (Oliver Quast) who builds our successful Danish tours.”

Based in Herning, which is in the centre of west Jutland (hence the “midwest” reference), in the Herning Museum of Contemporary Art (HEART), EMV consists of five string players, a pianist and a wind quintet. As Fung pointed out, “They bring an incredible flexibility to their playing, as the size of their ensemble shrinks and expands to the benefit of the repertoire and their programming. Think of a team of chefs that each have their specialty, but only called to the fore when the menu calls for it.”

Their Walter Hall concert will see six members of EMV joined by American clarinet virtuoso, Charles Neidich, “a celebrated luminary of the clarinet” as Fung dubbed him, in a program that focuses on the ensemble’s piano-wind nexus. Danish composer Carl Nielsen’s Fantasy: Pieces for Oboe and Piano Op.2 opens the recital and I was able to get a sense of it by sampling EMV’s cpo CD, Neilsen: Complete Chamber Works for Winds. I was struck by the richness of Peter Kristein’s singing tone on the oboe in the Romance and look forward to hearing him and pianist Martin Qvist Hansen live. Mozart’s Quintet for Piano and Winds in E-Flat Major K452 stands at the pinnacle of writing for piano, oboe, clarinet, bassoon and horn. I have been in love with it since childhood when my father introduced me to the Angel LP with pianist Walter Gieseking and the Philharmonia Wind Quartet that included the legendary hornist Dennis Brain.

Two months after Schubert finished writing Die schöne Müllerin, he took the 18th song in the cycle (Faded Flowers) and used it as the basis of a set of variations, Introduction and Variations on “Trockne Blumen” for Flute and Piano D802 Op posth.160. A solemn introduction leads into the gentle bucolic theme and as the variations progress the flutist is called on to convey beauty, tempestuousness, vulnerability and propriety. Flutist Charlotte Norholt, who will perform the work here in March, said before EMV’s first appearance at Carnegie Hall in 2012 (in a Danish video available on YouTube) that “the quest for musical excellence is the driving force of this ensemble.”

For Brahms’ Clarinet Trio in A Minor Op.114, cellist Jonathan Slaatto joins pianist Hansen to welcome back special guest Neidich for this enduring late-in-life masterpiece that was inspired by the same clarinetist (Richard Mühlfeld) who led Brahms to write his equally memorable clarinet quintet and sonatas. Slaatto, in that same YouTube video from 2012, expressed part of what makes EMV (and any good ensemble) tick when he said, referring to finding a suitable tempo, that your own view of any piece is subordinate to the view of the group as a whole.

Fung told me that he “was lucky to nab EMV on the same trip they are playing New York’s Carnegie Hall (their third appearance with them).” I suspect the Mooredale audience will agree after hearing their March 13 concert.

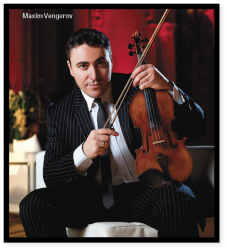

Maxim Vengerov. On March 11, the universally acclaimed violinist, the extraordinary Maxim Vengerov, makes his first recital appearance in Toronto since a right shoulder injury and recovery from surgery forced him to suspend playing for four years in 2007. His Roy Thomson Hall concert with pianist Patrice Laré, presented by the Montreal Chamber Music Society, will include Franck’s emotionally rich classic, Sonata for Violin and Piano in A Major, Ysaÿe’s devilishly difficult, unaccompanied Sonata for Violin No.6 as well as music by Brahms and Paganini.

Maxim Vengerov. On March 11, the universally acclaimed violinist, the extraordinary Maxim Vengerov, makes his first recital appearance in Toronto since a right shoulder injury and recovery from surgery forced him to suspend playing for four years in 2007. His Roy Thomson Hall concert with pianist Patrice Laré, presented by the Montreal Chamber Music Society, will include Franck’s emotionally rich classic, Sonata for Violin and Piano in A Major, Ysaÿe’s devilishly difficult, unaccompanied Sonata for Violin No.6 as well as music by Brahms and Paganini.

I got a sense of Vengerov’s journey back, which involved an assiduous rehab and reinvention of his violin technique from much reportage on the Internet, particularly Laurie Niles’ revelatory violinist.com interview published on January 9, 2013. In that interview, Vengerov also spoke of his close relationship to cellist/conductor Mstislav Rostropovich and pianist/conductor Daniel Barenboim, both of whom he got to know as a teenager.

Of Rostropovich, Vengerov says he was “like a musical father, he was so close to my heart; I think it was his great musicianship and also understanding of the violin repertoire, of the stringed instruments, that helped us to build an incredible chemistry that I had with no one else.”

Barenboim, Vengerov says, would “view a piece of music as an instrumentalist, as a pianist, from the harmonic point of view, from the orchestration, colouring,” whereas Rostropovich had an “instant connection with the composer, with the soul of the composer,” imagining he was the composer himself performing the music.

Of course Vengerov himself has conducted successfully (as anyone in the audience in October of 2012 at Roy Thomson Hall was only too aware, for his historic double role as soloist/conductor with the TSO in an exceptional performance of Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherazade), but the violin remains his “first source of communication with the audience – no doubt my first love.”

Vengerov looked at the time when he couldn’t play as beneficial to deepening his musical knowledge. “I think I have more colours to my violin playing than before, for the fact that I hear it somehow differently.” He also discovered, after surgery, that he had to change his technique so that he moves much less; he had been putting too much physical effort into his playing. Working with quite a lot of pain forced him to relax his playing. “If I had pain, that meant I was doing something wrong,” he said.

All in the service of the music, of “the great heritage Beethoven, Brahms, Shostakovich, Tchaikovsky left for us. We have to deliver these great works in the best possible way that we can. We have to find a very personal approach to them. Every soloist nowadays has to try to say something unique, something personal. Otherwise, if you’re playing just another performance of Brahms’ concerto, why do we need to hear that? That is the great lesson that Barenboim taught me…Just study the score…I want to really hear your Sibelius, your discovery, based on your new, detailed knowledge of the musical score.”

Takemitsu in Kyoto. An unexpected delivery of a DVD recently rekindled memories of Toru Takemitsu, who won the Glenn Gould Prize six years before Pierre Boulez. The DVD, Kyoto, is a quasi-documentary, part travelogue, atmospheric portrait of a place and a lifestyle, made in 1968 by the Japanese master filmmaker Kon Ichikawa (The Makioka Sisters) with a soundtrack by Takemitsu, then in his late 30s. Its 37 minutes are densely packed with artfully composed images that treat a rock garden, a Buddhist temple and a royal villa with the same aesthetic respect as that given to the people who walk the city’s streets. Takemitsu’s music, mysterious and quietly surprising but always filled with a deep humanity, acts as the foundation that illuminates these images. With a modernist sensibility always conscious of a cultural past, his score is an essential component of this fascinating piece of cinematic art. The handsomely packaged DVD is available from martygrossfilms.com. Many years ago, I was fortunate to be invited to watch Takemitsu at work one afternoon supervising the marriage of music, sound design and image in Marty Gross’ exquisite Bunraku film, The Lovers’ Exile. Takemitsu’s attention to detail, personal warmth and humility made a lasting impression.

QUICK PICKS

Music Toronto: If you’re quick off the mark you may be fortunate enough to hear the eminent British pianist Steven Osborne Mar 1. On Mar 10 the exuberant Montreal string ensemble, collectif9, performs a diverse program including Geof Holbrook’s Volksmobiles, from collectif9’s CD of the same name which Strings Attached DISCoveries’ columnist Terry Robbins praises elsewhere in these pages. Mar 17 the ebullient Quatuor Ébène’s strong program begins with Mozart’s delightful Divertimento K136, moves to Debussy’s Quartet in G Minor (a piece they own) before concluding with Beethoven’s immortal String Quartet No.14 Op.131. Apr 5 Duo Turgeon, husband-and-wife duo pianists, perform a heavyweight program that includes a new arrangement of Ravel’s Second Suite from Daphnis and Chloe by Vyacheslav Gryaznov, Lutoslawski’s Variations on a Theme by Paganini and Brahms’ Variations on a Theme by Haydn as well as pieces by the Russian Valery Gavrilin and the Canadian Derek Charke.

Music Toronto: If you’re quick off the mark you may be fortunate enough to hear the eminent British pianist Steven Osborne Mar 1. On Mar 10 the exuberant Montreal string ensemble, collectif9, performs a diverse program including Geof Holbrook’s Volksmobiles, from collectif9’s CD of the same name which Strings Attached DISCoveries’ columnist Terry Robbins praises elsewhere in these pages. Mar 17 the ebullient Quatuor Ébène’s strong program begins with Mozart’s delightful Divertimento K136, moves to Debussy’s Quartet in G Minor (a piece they own) before concluding with Beethoven’s immortal String Quartet No.14 Op.131. Apr 5 Duo Turgeon, husband-and-wife duo pianists, perform a heavyweight program that includes a new arrangement of Ravel’s Second Suite from Daphnis and Chloe by Vyacheslav Gryaznov, Lutoslawski’s Variations on a Theme by Paganini and Brahms’ Variations on a Theme by Haydn as well as pieces by the Russian Valery Gavrilin and the Canadian Derek Charke.

Royal Conservatory: I wrote in my last column about the talented young Norwegian violinist Vilde Frang and her Koerner Hall debut Mar 2. She’s followed Mar 4 by Canadian violinist Karen Gomyo, Swiss cellist Christian Poltéra and Finnish pianist Juho Pohjonen in an appealing program of Mittel-European fare. On Mar 20 Paul Lewis performs his first solo recital in this city since his remarkable Toronto debut with the Women’s Musical Club in the fall of 2013. In this upcoming Koerner Hall concert, he focuses on Brahms (Four Ballades Op.10; Three Intermezzi Op.117), Liszt (the transformative Après une lecture du Dante, fantasia quasi una sonata, “‘Dante Sonata” from Années de pèlerinage, Italie) and Schubert (the enchanting Sonata D575). On Mar 29 the current crop of Rebanks fellows are on display in a recital in Mazzoleni Hall, which is also the venue Apr 7 for chamber music by Haydn, Berg (the uber-Romantic Lyric Suite) and Dvořák (the charming Piano Quintet No.2 Op.81) performed by the Musicians from Marlboro. In Koerner Hall on Mar 30 violinist Augustin Dumay and pianist Louis Lortie bring their powerful musical gifts to sonatas by Beethoven (“Spring”), Franck and Richard Strauss.

Perimeter: Best known as artistic directors of the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center, husband-and-wife cellist David Finckel and pianist Wu Han bring their considerable performing talents to the Perimeter Institute Mar 10, in a program of music by Richard Strauss, Chopin, Messiaen, Glazunov and Albéniz.

Nocturnes in the City: Pianist Adam Zukiewicz plays Beethoven and Liszt Mar 13. (One evening earlier, Mar 12, Zukiewicz plays a similar program at St. Basil’s Church.) The Czech-based Epoque Quartet plays Vivaldi, Jezek and others at the Praha restaurant Mar 27. Notable Czech pianist and Smetana specialist, Jan Novotný, makes a welcome visit to Toronto for a recital that includes music by Smetana, Schubert and Mozart.

Kitchener-Waterloo Chamber Music Society: The final weekend of the Attacca Quartet’s Haydn 68 series takes place Mar 18, 19 and 20; since their last appearance in the KWCMS Music Room, the quartet has a new violist, Nathan Schram. (My Q & A with the KWCMS’ Jean and Jan Narveson and interview with former Attaca violist Andrew Fleming appeared in The WholeNote’s November 2013 issue as the complete Haydn string quartet cycle began.) Mar 24 cellist Rachel Mercer and pianist Angela Park perform the complete Mendelssohn works for cello; on Apr 3 they join violinist Elissa Lee and violist Sharon Wei, their partners in Ensemble Made in Canada, for a Syrinx concert of music by Beethoven, Schumann and Omar Daniel.

Academy Concert Series presents Mozart’s masterful Sinfonia Concertante K364 for violin, viola and orchestra, and Beethoven’s first sonata for cello and piano, Op.5 No.1, transcribed by nineteenth-century arrangers for string sextet and cello quintet, respectively, Mar 19. Also Mar 19, Jeffery Concerts presents the TSO Chamber Soloists – Nora Shulman, flute, Teng Li, viola, Jonathan Crow, violin, Heidi Van Hoesen Gorton, harp, and Joseph Johson, cello, in a program of music by Françaix, Saint-Saëns, Debussy, Ravel and Jongen.

The TSO: Stéphane Denève, principal conductor of the Philadelphia Symphony Orchestra, leads the TSO in a crowd-pleasing program Mar 23 and 24 that features the charismatic Jean-Yves Thibaudet as soloist in Saint-Saëns’ exotic Piano Concerto No.5 “Egyptian.” On Mar 31 the TSO presents the Victoria Symphony conducted by Tania Miller with Stewart Goodyear as soloist in Grieg’s lyrical Piano Concerto. Soprano Carla Huhtanen, poet Dennis Lee and narrator Kevin Frank join conductor Earl Lee in two afternoon Young People’s Concert performances Apr 2 of Abigail Richardson-Schulte’s musical treatment of Lee’s iconic children’s classic, Alligator Pie. It would be a surprise if Gabriela Montero didn’t improvise her own cadenza in Mozart’s sublime Piano Concerto No.20 K466 when she appears as soloist with the National Arts Centre Orchestra under its new conductor Alexander Shelley Apr 2; two of Richard Strauss’ most exciting tone poems, Don Juan and Death and Transfiguration open and close the concert.

Massey Hall/Roy Thomson Hall presents Chopin champion Yundi in his first Toronto recital in a decade Mar 19; the famously conductorless Orpheus Chamber Orchestra features Pinchas Zukerman as soloist in Mozart’s Violin Concerto No.3 K216, a masterpiece of gallantry and lightness, and in Beethoven’s tender First Romance, Mar 20.

Canzona presents the XIA Quartet – Edmonton Symphony Orchestra concertmaster Robert Uchida and Toronto Symphony Orchestra members, violinist Shane Kim, assistant principal violist, Theresa Rudolph, and principal cellist, Joseph Johnson, playing music by Bartók, Debussy and Schubert, Mar 20 at St. Andrew by-the-Lake, on Toronto Island, repeated Mar 21 on the mainland.

Three years ago, Rashaan Allwood was the very rare recipient of a perfect 100 in his ARCT Royal Conservatory exam. Now he’s a U of T student with an upcoming free recital Mar 26 at Walter Hall of piano music inspired by birdsong and nature – Messiaen, Ravel, Liszt, Granados and others.

Last month I wrote about Andrew Burashko, Art of Time Ensemble’s founder and artistic director; the group’s unmissable next concert, “Erwin Schulhoff: Dada, Jazz and the String Sextet: Portrait of a Forgotten Master,” takes place Apr 1 and 2 at Harbourfront Centre Theatre.

Following their playing of Mendelssohn’s engaging String Quartet No.2, U of T Faculty of Music ensemble-in-residence, the Cecilia String Quartet is joined by James Campbell for a performance of Brahms’ Clarinet Quintet, a cornerstone of the clarinet repertoire, Apr 4.

The COC orchestra’s top two violinists, Marie Bérard and Aaron Schwebel, give a free noontime concert featuring music by Ysaÿe and Leclair, in the Richard Bradshaw Amphitheatre, Apr 5.

Paul Ennis the managing editor of The WholeNote.