Johnny Cowell Ninety and Still Counting!

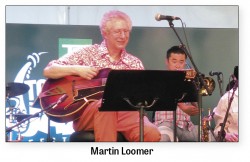

For most of us the arrival of January heralds the beginning of a new year or the departure from an old year. For some it marks the beginning of a new decade in their lives. A few days ago I had the pleasure of attending the birthday party for one such person. It was trumpeter Johnny Cowell’s 90th birthday party. Johnny and Joan, his wife of 60-plus years, were the very special guests.

For most of us the arrival of January heralds the beginning of a new year or the departure from an old year. For some it marks the beginning of a new decade in their lives. A few days ago I had the pleasure of attending the birthday party for one such person. It was trumpeter Johnny Cowell’s 90th birthday party. Johnny and Joan, his wife of 60-plus years, were the very special guests.

Johnny has been a prominent part of the Toronto music scene for 70 years. His trumpet playing in Toronto started at age 15 when he travelled from his home town of Tillsonburg, Ontario, and began playing in the Toronto Symphony Band. However, there was a war on, and as soon as he was old enough, he enlisted in the navy. Within weeks of his enlistment, Johnny was the trumpet soloist in the band of HMCS Naden, the principal Canadian Navy base in Esquimault, B.C.

As we chatted at his birthday party, I started to wonder if our paths might have crossed on more than one occasion over the years. After all, our birthdays are less than a month apart and we both started playing in bands at an early age. Actually Johnny started when, at age five, he was given a used trumpet by his uncle. I didn’t start until I was 13. I lived in a larger community than Tillsonburg and, in addition to adult bands, we had a boys’ band. His first band experience was with the Tillsonburg Citizens’ Band.

A few months ago I mentioned in this column how small-town summer-band tattoos were a significant part of a band member’s life. I had played in many such tattoos in Southwestern Ontario. As we chatted, it turned out Johnny had not only played in many of the same tattoos, he had played trumpet solos in these events. As for music festivals, such as those in Waterloo or the Stratford Music Festival with Professor Thiele, the answer was the same. We had both been at them.

As teenagers playing in community bands at the same tattoos and festivals, we never met. Even though we both joined the navy at the same age and at about the same time, our paths never crossed there. It was only years later that, in a musical situation reminiscent of our teenage years, we met, playing once again in a marching band. It may seem hard to believe today, but in the early 1960s the Toronto Argonauts had their own professional marching band which performed fancy routines on the field at all home games. Some may have thought that this was below one’s dignity or not in keeping with professional musical standards. However, why not get well paid to go to see the hometown team play football? So that is where we met.

While Johnny is best known for his trumpet virtuosity, he has won considerable acclaim as a writer and arranger. In fact, on more than one occasion he turned down attractive offers which might have brought him fame by writing for stage productions or getting involved in the Nashville scene. However, the trumpet, his all-abiding first musical love, second only to that for his wife Joan and their family, always won out. Offers which would inevitably have separated him from his trumpet were declined.

Even though he elected to stay home and play trumpet, Johnny certainly did not turn his back on writing. I couldn’t hope to count how many of his tunes could be heard on the radio in the 60s. His 1956 ballad Walk Hand in Hand could be heard on every radio station in those days. His writing wasn’t limited to that genre. He has been equally at home writing for trumpet and brass ensembles. Playing a few selections from the Johnny Cowell CDs in my collection, I am amazed at the broad gamut of his trumpet works. At one end of the spectrum there is his dazzling Roller Coaster, and on the other end, his Concerto in E Minor for Trumpet and Symphony Orchestra. While he is officially retired, he still practises on his trumpet regularly and is expecting to be a guest soon with the Hannaford Junior Band playing his composition Roller Coaster with members of that group.

As I sat down for a brief chat with Johnny and 94-year-old Eddie Graf, who is still playing and writing arrangements, I was humbled to say the least.

A weekend of special programs: The weekend of February 27 and 28 stands out as a special one for aficionados of the music of wind ensembles. First, on Saturday we have the Silverthorn Symphonic Winds continuing their 2015/2016 season with a program called “Musician’s Choice,” where those planning the program have consulted band members to determine what music they would like to perform. They have chosen a broad spectrum from Howard Cable’s The Banks of Newfoundland to Shostakovich’s Festive Overture. Within that spectrum they take their audience all the way from Percy Grainger’s Irish Tune from County Derry to Norman Dello Joio’s Satiric Dances and Steven Reineke’s The Witch and the Saint. This latter number is a tone poem depicting the lives of twin sisters Helena and Sibylla, born in Germany in 1588 at a time when twin children were considered a very evil omen. As the story unfolds, instruments in the band which seldom get solos have an opportunity to employ their special sounds to tell the story of the twins during their lives. If that isn’t enough, the band might just be able to squeeze in some excerpts from Leonard Bernstein’s Candide. It all takes place Saturday, February 27, at 7:30pm at Wilmar Heights Event Centre.

The following evening the Wychwood Clarinet Choir will present their “Midwinter Sweets.” Exploiting the unique sounds of a clarinet ensemble to the full, they will feature Red Rosey Bush by composer and conductor laureate Howard Cable. The composing and arranging talents of choir member Roy Greaves come to the fore in his composition Trois Chansons Québécoises and his arrangement of Gustav Holst’s St. Paul’s Suite. That’s Sunday, February 28, at the Church of St. Michael and All Angels.

Elsewhere in the band world

February 4 and March 3. The Encore Symphonic Concert Band presents their monthly noon-hour concert of “Classics and Jazz,” with John Edward Liddle conducting at Wilmar Heights Centre.

February 5 at 7:30, as part of the U of T Faculty of Music New Music Festival, you can hear Rosauro’s Concerto for Marimba performed by Danielle Sum.

February 7 at 3pm at Knox Presbyterian Church in Waterloo (and repeated on February 21 at 3pm at Grandview Baptist Church in Kitchener) the Wellington Wind Symphony offers “Remembering” with works by Brahms, Erwazen, Woolfenden and Alford. Also on the program will be Morawetz’s In Memoriam for Martin Luther King, Jr.

February 21 at 3pm The Hannaford Street Silver Band will present “German Brass” with Fergus McWilliam, French horn, and James Gourlay, conductor.

February 23 at 7:30 The Metropolitan Silver Band will present “Jubilee Order of Good Cheer,” a blend of classics, marches, sacred, popular and contemporary works at Jubilee United Church.

For details on all these consult The WholeNote concert listings.

Calling all brass: For a number of years, the Canadian Band Association, Ontario has held Community Band Weekends sponsored by a number of community bands in various communities across the province. This year there is a new twist. For the first time, CBA-Ontario will host a Community Brass Band Weekend from Friday evening February 19 to Sunday, February 21. Hosted by the Oshawa Civic Band, the event should not only offer a meeting ground for dedicated brass band devotees but introduce brass players from concert bands to the style and repertoire of the All Brass culture. All musical events will take place at Trulls Road Free Methodist Church, 2301 Trulls Road S., Courtice. Details on registration were spotty at time of writing: consult cba-ontario.ca/cbw-registration for updates.

We have another new all-brass band to report on. The York Region Brass began rehearsals in Newmarket a few months ago and are inviting brass players to join them. They rehearse on Wednesday evenings and would particularly welcome cornet, trombone and tuba players. If you play a brass instrument and are interested in exploring that genre contact Peter Hussey by email at pnhussey@rogers.com.

Another special musical event: Although it has nothing whatsoever to do with band music, I can’t end without reporting on a recent outstanding musical event in Toronto. The Amadeus Choir, the Elmer Iseler Singers and the Toronto Symphony Orchestra, under the direction of Bernard Labadie, performed a special “semi-staged” version of Mozart’s Requiem K626. The combined choirs, soloists and conductor, all performing the entire work from memory, gave this monumental work new meaning. Through movements and gestures, conceived by stage director Joel Ivany, choir members and soloists conveyed the concept of loss and redemption that is the heart of the requiem mass. To set the mood for the choral work, as a prelude, the TSO Chamber Soloists performed the Largetto movement from Mozart’s Clarinet Quintet in A Major, K581.

Jack MacQuarrie plays several brass instruments and has performed in many community ensembles. He can be contacted at bandstand@thewholenote.com.