Happy St. Patrick’s Day from the Great Irish Jazz Pianists

St. Patrick’s Day came and went between this issue of WholeNote and the last, so I thought it would be fun to acknowledge my Irish descent – the key word being descent, as in “into madness” – by taking a look at the grand legacy of Irish jazz piano. There have been many more fine Irish jazz pianists than many people realize and here they are, in chronological order:

Ellis Larkins – Larkins hailed from Baltimore, County Cork. He was something of a child prodigy, performing with local orchestras by the age of ten. After graduating from the distinguished Peabody Conservatory in his hometown, Larkins became the first jazz pianist to attend the famed Jewel Yard School of Music in Dublin and began his long career after graduation. Larkins had a gossamer touch resulting in a translucent sound, a deft harmonic sense and a sensitivity which made him a great accompanist, especially of singers. He spent many years as a vocal coach and was the regular pianist for a number of fine vocalists including Mabel Mercer, Sylvia Syms and the First Lady of Irish Song, Ella Fitzgerald. Along with his own natural reticence, this supportive role meant Larkins was one of the more overlooked Irish pianists, although musicians like Ruby Braff, with whom he often recorded in a duo, knew his true worth.

Ellis Larkins – Larkins hailed from Baltimore, County Cork. He was something of a child prodigy, performing with local orchestras by the age of ten. After graduating from the distinguished Peabody Conservatory in his hometown, Larkins became the first jazz pianist to attend the famed Jewel Yard School of Music in Dublin and began his long career after graduation. Larkins had a gossamer touch resulting in a translucent sound, a deft harmonic sense and a sensitivity which made him a great accompanist, especially of singers. He spent many years as a vocal coach and was the regular pianist for a number of fine vocalists including Mabel Mercer, Sylvia Syms and the First Lady of Irish Song, Ella Fitzgerald. Along with his own natural reticence, this supportive role meant Larkins was one of the more overlooked Irish pianists, although musicians like Ruby Braff, with whom he often recorded in a duo, knew his true worth.

Harold McKinney – McKinney was born into a musical family in that hotbed of Irish jazz, Moughtown (pronounced “mow”), County Monaghan. One of his brothers, Bernard, played the euphonium and another, William, was a bassist. They bear no relation to the William McKinney who led the seminal Irish big band McKinney’s Flax Spinners. Harold McKinney might have achieved more notoriety had he left Moughtown for Dublin, as did many of the city’s younger pianists, but he preferred to remain there in the role of elder and mentor, for which he was much treasured.

Dave McKenna – McKennna was from the Aran Islands and eventually emigrated to Boston and later New York, where he was the favourite pianist of such American-Irish greats as Bobby Hackett and Zoot Sims. A huge, anvil-headed man with massive hands who looked like the captain of a whaling boat, he was the most two-fisted of Irish pianists, developing a driving and very full style often displayed in solo outings. His two-fistedness was often seen offstage as well, with a pint of Guinness in his left hand and a small one of Jameson’s in his right. He was also renowned for his almost limitless repertoire, often weaving seemingly disparate songs into long and ingeniously witty medleys.

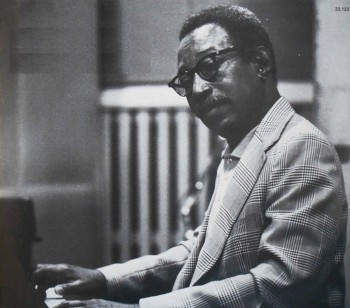

Tommy Flanagan – Easily my favourite Irish pianist, Flanagan was part of the large wave of young musicians, many of them pianists, to emerge from Moughtown in the mid-1950s. His very fluent playing showed both the delicacy of Teddy Wilson and the toughness of Bud Powell, his two main influences. He was very much of the lace-curtain school of Irish jazz piano; there never was one who played with more lilting grace or elegance. Like Ellis Larkins, he was naturally standoffish and served a long apprenticeship as a sideman, including several stints as Ella Fitzgerald’s accompanist in the 1960s and 70s. He appeared on hundreds of records, including a couple of seminal ones in Irish history: Giant’s Causeway Steps with the great Ulster tenor John Coleraine, and The Incredible Jazz Guitar of Wes Montgomery, with Eire’s most celebrated plectrist. Eventually in his forties, Flanagan lit out on his own as a leader with a long series of fine trio records. By the time he died in 2001 he was known as “The Poet of the Piano.”

Armagh J. O’Malley – Born Fritz Peterson, O’Malley eventually adopted a more Irish name taken from his home county in Ulster. He later emerged in the centrally located Shightown with a fine trio, which exerted considerable influence on both the repertoire and rhythmic approach of the mid-1950s’ Miles Davis quintet, bringing him lasting fame in spite of indifference from many critics. Despite virtuosic technique, he played with a very sparse, probing style, often concentrating on the piano’s upper register, and displayed a brilliant knack for arranging unlikely pieces for piano trio, using ingenious vamps and interludes to fully integrate the bass and drums. He was one of the first jazz pianists to become a Steinway Artist and is still going strong. He will turn 88 this July, a special age for a pianist given the number of keys on the instrument.

Wynton Kelly – In contrast to Tommy Flanagan, Kelly developed a hard-swinging, funky, blues-infused style of great craic and spirit much more in keeping with the thatched-roof school of Irish jazz piano. He hailed from the large Dublin borough of Brooke Lynn and went on to form important associations with Miles Davis and Wes Montgomery, often in the company of his long standing trio of bassist Paul Chambers and drummer Jimmy Cobh, who hailed from the small port just south of Cork. He died far too young, but Kelly was the most joyous of Irish pianists.

(For those not familiar with the designations lace-curtain and thatched-roof Irish, the former tend to be more urban and genteel, more prosperous and “of the quality” as the Irish would put it. Thatched-roof Irish are more lively, down to earth and working class, often dwelling in modest rural cottages. The following old joke may help drive the distinction home: What’s the difference between lace-curtain Irish and thatched-roof Irish? The lace-curtain Irish take the dishes out of the sink before they pee in it.)

Roland Hanna – Hanna is another of the fine pianists to emerge from the hyperactive Moughtown jazz scene. He had an eclectic modern approach and was one of the few players influenced both by bebop pianists and Erroll Garner. A great favourite of that noted jazz fan Queen Elizabeth II, he was knighted by her and thereafter known as Sir Roland Hanna, causing no small dismay among his more republican fans, some of whom referred to him as “that poxy royalist bastard.” He survived a couple of knee-capping attempts but eventually won over his doubters by remaining true to his Irish musical roots of lyricism wed with inventiveness.

McCoy Tyner – Tyner came to prominence as a young man when he joined the classic 1960s quartet of renowned Ulster tenor John Coleraine. Tyner developed a rhythmically powerful attack using the 6/8 rhythms and triplets common to Irish jigs and reels, while exploring the modern applications of traditional Irish modality using Uilleann pipe modes and the quartal harmonies of the puntatonic scale. Apart from the Coleraine quartet he made many fine trio recordings as a leader.

Chick O’Rea – O’Rea began in his teens as a percussionist, playing the bodhran in traditional Irish groups. His inherent brilliance as a pianist soon took over, as did his more modern tendencies. He was one of the key Irish pianists in the fusion movement as leader and sideman and has shown a restless spirit in switching back and forth between both electric and acoustic bands and instruments. Indeed, #Corea (as he hashtags himself these days) has at times had difficulty deciding whether he wants to be a popular musician or an uncompromisingly creative one and this dichotomy shows in his music. His 1978 release The Leprechaun was an unabashed exploration of his Irish musical heritage.

Joanne Brackeen – Against all odds, Brackeen (nee Joanne Grogan) managed to break through the more hidebound strictures of traditional Irish society, demonstrating the deeply matriarchal roots of the small island, all those priests notwithstanding. Early in her career she accompanied the noted Irish tenors Stan Getts and Joe Henderson before establishing herself as a leader. Her style can be a little on the challenging and explosive side, but her inventiveness could also be very lyrical and melodic. She often performed with the Irish rhythm team of bassist Cecil McBee and drummer Aloysius Foster.

Todd O’Hammer – O’Hammer is a stalwart of modern Irish bebop, both as an active sideman and as a leader of his own trios. He has performed with such veterans as Charlie Rouse, Johnny Griffin, Art Farmer, and George Coleman, and regularly accompanied the singer Annie Ross. His playing is steeped in the jazz tradition but he continues to look forward, always sounding fresh.

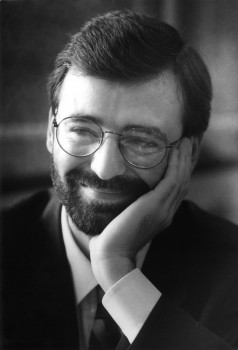

Rossan O’Sportiello – At just 43, O’Sportiello is the most recent arrival on this list, and yet he is something of a stylistic throwback, often performing in a mainstream/swing style of catholic breadth. He is a dynamic virtuoso in the tradition of Art Tatum and Teddy Wilson, also showing a fondness for such pianists as Ralph Sutton, Barry Harris and the aforementioned Dave McKenna. He has built a solid international reputation working with many fine jazz artists as well as through his own recordings. Toronto fans may know him from his sparkling performances at the last few Ken Page Memorial Trust All-Star fundraiser concerts at the Old Mill.

Rossan O’Sportiello – At just 43, O’Sportiello is the most recent arrival on this list, and yet he is something of a stylistic throwback, often performing in a mainstream/swing style of catholic breadth. He is a dynamic virtuoso in the tradition of Art Tatum and Teddy Wilson, also showing a fondness for such pianists as Ralph Sutton, Barry Harris and the aforementioned Dave McKenna. He has built a solid international reputation working with many fine jazz artists as well as through his own recordings. Toronto fans may know him from his sparkling performances at the last few Ken Page Memorial Trust All-Star fundraiser concerts at the Old Mill.

So there you have them, the great Irish jazz pianists. To all music fans, sláinte, and a belated Happy St. Patrick’s Day.

Toronto bassist Steve Wallace writes a blog called “Steve Wallace – jazz, baseball, life and other ephemera” which can be accessed at wallacebass.com. Aside from the topics mentioned, he sometimes writes about movies and food.