Drilling Down into Operatic Bedrock

With the Canadian Opera Company sleeping off the effects of Turandot and Rusalka, its two wildly contrasting fall main stage blockbusters, top spot in the operatic food chain this month goes to Opera Atelier’s remount of their convention-bucking, commedia-based Don Giovanni, in their new digs at the Ed Mirvish Theatre (formerly the Pantages) on Yonge Street, a big block north of OA’s longtime regular venue at the Elgin Theatre (now hosting an indefinite, and presumably lucratively lengthy, run of Come From Away).

Don Giovanni opens October 31, one day before this issue hits the streets, but if you’re fast out of the blocks, you can still catch it November 2, 3, 8 and 9. And catch it you should, especially if you’re allergic to the heavy-handed Bergmanesque moralizing gloom that all too often accrues to this work. Mozart would have recognized the style of this production far more readily (and I dare say delightedly) than some of the other gloomily lit treatments it has received.

Don Giovanni opens October 31, one day before this issue hits the streets, but if you’re fast out of the blocks, you can still catch it November 2, 3, 8 and 9. And catch it you should, especially if you’re allergic to the heavy-handed Bergmanesque moralizing gloom that all too often accrues to this work. Mozart would have recognized the style of this production far more readily (and I dare say delightedly) than some of the other gloomily lit treatments it has received.

“Fast out of the blocks” will also need to be the operative phrase if you want to take advantage of the period covered in this issue to drill down into five other strata of activity that are the bedrock of opera as a lively art in our region: our universities and conservatories; our regional opera companies; a vibrant indie opera scene, constantly reinventing itself; a rich tradition of community-based performance – participation in opera for the sheer love of it; and a decades-long tradition of opera-in-concert presentation of works we might otherwise, for various reasons, never have the opportunity to see and hear.

Universities and conservatories: Nov 1 and 2, at Mazzoleni Concert Hall, the Royal Conservatory’s Glenn Gould School gets things rolling with its fall chamber opera: a production of English composer Jonathan Dove’s Siren Song (libretto by Nick Dear). It’s a 70-minute work for five singers, one actor, and an orchestra of ten players (here conducted by Peter Tiefenbach), based on “a bizarre, true story of a young sailor who exchanges letters with a beautiful and successful model. Over time, a romantic and passionate relationship develops, but a meeting proves increasingly difficult to arrange.”

Later in the month, a short stroll down Philosopher’s Walk from the Royal Conservatory, the University of Toronto Faculty of Music gets into the act, twice. Nov 21, 22, 23, and 24, in the MacMillan Theatre, Edward Johnson Building, the Opera School presents Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro, with two casts getting two shows each, and an “Opera Talk” lecture half an hour before each concert. And then, Dec 5, the U of T Symphony Orchestra gets into the act with a program titled Operatic Showpieces, featuring U of T Opera and the MacMillan Singers, conducted by COC chorus master Sandra Horst and Uri Meyer.

And if that’s not enough, or you live westwards, head down the 401 to the Don Wright Faculty of Music in London, where, on the same dates (Nov 21, 22, 23, and 24) Opera at Western presents Mozart’s The Secret Gardener (La Finta Giardiniera), penned at the ripe old age of 18! Stage direction by renowned baritone Theodore Baerg.

Regional and community opera: Nov 1 and 3 also offer an opportunity to observe Opera York in action, in Verdi’s La Traviata, at the Richmond Hill Centre for the Performing Arts, one of two fully staged operas they will present this season. (The other will be Lehar’s Merry Widow, Feb 28 and Mar 1.) This tenacious company’s mission is “to provide professional opera that is accessible financially, geographically and comprehensibly to the communities of York Region and surrounding communities, to encourage the development of the art form through educational and outreach activities and provide a platform for emerging and established Canadian artists” and they stick to it, as reflected in the quality of their casts. An example from this show: Natalya Gennadi (Violetta), whose Dora-nominated title role in Tapestry Opera’s Oksana G. in 2017 was widely praised. NOW Magazine called it “stunning... piercing in its openness and vulnerability.”

Regional and community opera: Nov 1 and 3 also offer an opportunity to observe Opera York in action, in Verdi’s La Traviata, at the Richmond Hill Centre for the Performing Arts, one of two fully staged operas they will present this season. (The other will be Lehar’s Merry Widow, Feb 28 and Mar 1.) This tenacious company’s mission is “to provide professional opera that is accessible financially, geographically and comprehensibly to the communities of York Region and surrounding communities, to encourage the development of the art form through educational and outreach activities and provide a platform for emerging and established Canadian artists” and they stick to it, as reflected in the quality of their casts. An example from this show: Natalya Gennadi (Violetta), whose Dora-nominated title role in Tapestry Opera’s Oksana G. in 2017 was widely praised. NOW Magazine called it “stunning... piercing in its openness and vulnerability.”

Later in the month, and proudly rooted at the community opera end of things for 73 years, on Nov 21 and 23, Toronto City Opera, formerly known as Toronto Opera Repertoire, presents Offenbach’s Les contes d’Hoffmann, at the Al Green Theatre, 750 Spadina. Founded in 1946, by an optimistic James Rosselino, as an “Opera Workshop” at Central Technical School, in collaboration with the Toronto School Board, and now under the artistic direction of the multi-talented Jennifer Tung (singer, vocal coach, collaborative pianist, conductor), they present at least two fully staged operas each year with early-career paid-professional soloists selected after open auditions, and an amateur non-auditioned community chorus that remains open to all. The result is a wonderful sense of community engagement that extends through the chorus to the audience, many of whom are often having their first opera experience. Their mission statement – passionately committed to opera for everyone – says it all.

Later in the month, and proudly rooted at the community opera end of things for 73 years, on Nov 21 and 23, Toronto City Opera, formerly known as Toronto Opera Repertoire, presents Offenbach’s Les contes d’Hoffmann, at the Al Green Theatre, 750 Spadina. Founded in 1946, by an optimistic James Rosselino, as an “Opera Workshop” at Central Technical School, in collaboration with the Toronto School Board, and now under the artistic direction of the multi-talented Jennifer Tung (singer, vocal coach, collaborative pianist, conductor), they present at least two fully staged operas each year with early-career paid-professional soloists selected after open auditions, and an amateur non-auditioned community chorus that remains open to all. The result is a wonderful sense of community engagement that extends through the chorus to the audience, many of whom are often having their first opera experience. Their mission statement – passionately committed to opera for everyone – says it all.

Indie opera: With the recent buzz around Tapestry Opera’s 40th anniversary and the tenth anniversary tour of Against the Grain’s pub-based La Bohème, it’s easy to lose sight of the fact that independent opera in this town is fertile soil for much more. Just one example: Nov 2, 3 and 4, at Heliconian Hall, Loose Tea Music Theatre, under the always searching and provocative direction of Alaina Viau presents Singing Only Softly/The Diary of Anne Frank - Operas from the Secret Annex which pairs two separate works: Singing Only Softly, (composed by Cecilia Livingston with libretto by Monica Pearce); and The Diary of Anne Frank composed by Grigory Frid. Singing Only Softly Is based on the original, unredacted texts of the diary, “voicing Anne Frank as a fully formed young woman describing her experiences while discovering herself. Freshly interpreted in a current female context, it explores Anne’s complex self-awareness and self-representation.” Anne Frank is variously portrayed by sopranos Sara Schabas and Gillian Grossman, with music direction by Cheryl Duvall.

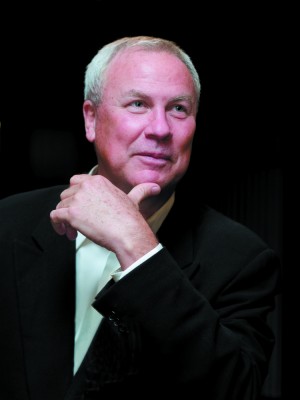

Opera in Concert: From the scope and scale of the Toronto Symphony Orchestra’s “Grand Opera in Concert” performances of Jules Massenet and Louis Gallet’s Thaïs, on Nov 7 and 9 at Roy Thomson Hall, to the intimate informality of Opera by Request’s Rossini’s Barber of Seville, Nov 15 at College St. United Church, opera in concert is alive and well as an art form in these parts. So it’s a fitting close to this exercise to give a special nod to a production by the company, now in its fifth decade, that pretty much single-handedly made the genre a natural and necessary part of the fabric of all things operatic around here: VOICEBOX: Opera in Concert’s presentation on Dec 1 of Leoš Janáček’s 1921 opera, Katya Kabanová.

Sung in English, the performance, in the company’s customary Jane Mallet Theatre surrounds, will feature Lynn Isnar, soprano; Emilia Boteva, mezzo; and tenors Michael Barrett and Cian Horrobin; with Jo Greenaway, music director/piano, and, as always, Robert Cooper, as chorus director. It’s not the opera that the brilliant 20th-century composer of Jenufa, The Cunning Little Vixen, and The Makropulos Affair is best known for. But that is the whole point. Opera in concert allows presenters, as play readings sometimes do, to bring to the eyes, and more importantly ears, of audiences, works that, for a range of reasons that have nothing to do with artistic quality, might otherwise be consigned to archival oblivion. And we would all be the poorer for it.

David Perlman can be reached at publisher@thewholenote.com.