This is an article of mostly personal recollections, thoughts of some friends no longer with us. But it’s not a column of obituaries. You can read them elsewhere. It’s just that the events of the past month have stirred up memories.

For example, I remember nights with Vic Dickenson when we would end up in his room after the gig. His favourite tipple was a scotch called Cutty Sark – not mine, but it took on a certain quality when sharing it with Vic who was for me the finest, most subtle and humorous of all the trombone players.

I learned so much from this gentle man. On the bandstand it was a music lesson just to stand beside him and listen, and after hours I marvelled at his knowledge of songs. “Do you know this one?” he would say and sing the verse and chorus to some lesser-known tune. He knew the lyrics to all of them and taught me that to interpret a ballad you should at least know what the lyric was saying. Only then could you really interpret the melody and “tell your story.” (There’s a wonderful anecdote about the tenor sax player Ben Webster, one of the greatest ballad players in all of jazz, who was unhappy with a chorus. When asked what was wrong, he said, “I forgot the words.”)

In these after-hours intimate times with Vic, if we emptied a bottle it was his habit to take the freshly opened replacement and pour the first few drops on the floor, saying, “For departed friends.” Well, in the past month alone I could have poured a fair amount of the golden liquid on my floor for four more departed friends.

John Norris, whose death was an enormous loss to the jazz world, was not a musician but was responsible for a huge legacy of writings and the recordings he produced for Sackville Records of which he was a founder/owner, making that label one of the most respected in the business. He dedicated his life to jazz and earned the love and respect of all the musicians whose life he touched. We travelled often together – to Europe, Britain, Australia and the United States – and became good friends over the 40-plus years that we knew each other.

Saxophonist/composer John Dankworth was not a close friend in the way that John Norris was, but we did share some enjoyable times together. One of my early recollections as a young bandleader in Glasgow was sharing the bandstand with my own group and the Johnny Dankworth Orchestra. The venue was Green’s Playhouse, a huge ballroom on Renfield Street with a sprung dance floor. To give some idea of its size, the hall was directly above the biggest cinema in Europe with seating for 4,368 patrons!

Over the years we saw each other on his visits to Toronto. Most recently, last May at the Norwich Jazz Party, I enjoyed some time with Johnny – now Sir John – who regaled us with stories at the dinner table and was still filled with love and enthusiasm for life and playing. On February 6 John died at age 82, having been ill since October. His last performance was at the Royal Festival Hall in London last December when, a trouper to the end, he played his saxophone from a wheelchair.

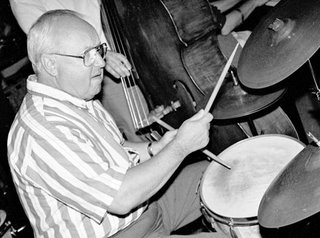

The passing of Jake Hanna at age 78 in Los Angeles on February 13 of complications from a blood disease was another tremendous loss. He was one of the great drummers, equally at home in small groups and big bands, and one of the unforgettable characters in jazz. If Jake was behind the drums, one thing was sure – the band would swing. He began his professional career in Boston and by the late 50s was playing with Marion McPartland and Toshiko Akiyoshi, as well as in the big bands of Maynard Ferguson and Woody Herman.

The passing of Jake Hanna at age 78 in Los Angeles on February 13 of complications from a blood disease was another tremendous loss. He was one of the great drummers, equally at home in small groups and big bands, and one of the unforgettable characters in jazz. If Jake was behind the drums, one thing was sure – the band would swing. He began his professional career in Boston and by the late 50s was playing with Marion McPartland and Toshiko Akiyoshi, as well as in the big bands of Maynard Ferguson and Woody Herman.

I bought my first car in Toronto in 1964, a beat-up old NSU Prinz, and drove it to Burlington because Woody’s band was playing at the Brant Inn. There, for the first time I heard Jake Hanna in person, making that great band swing mightily. At the time, of course, I had no idea that we were to become close friends and that he would one day make an album with my big band.

After the stint with Woody Herman, Hanna was a regular on the Merv Griffin television show, and when the show moved to the West Coast, Jake was one of a handful of players who made the move with Griffin. That job lasted until 1975, after which he played with a variety of groups including Supersax and Count Basie, and occasionally co-led a group with Carl Fontana. In addition, he was a fixture at festivals and jazz parties.

In a room full of musicians he was always a centre of attraction, telling stories from a seemingly endless collection of memories and cracking jokes with a dry humour that would have us all in stitches. He was the master of the one-liner on stage and off: “So many drummers, so little time.” Not all of them were original, but somehow Jake took ownership of them. If Jake liked you it was for life; if he didn’t it was also a pretty permanent arrangement. He was straight ahead in the way he played drums and straight as a die in the way he lived life. It just won’t be the same without him.

Earlier the same day I lost another good friend in cornet player Tom Saunders who died at age 71. Tom’s idol was Wild Bill Davison, a firebrand player and one of the great hot horn players. It was through Wild Bill that I met Tom and it began a friendship that lasted more than 40 years. Following in Bill’s footsteps he was recognized as one of the finest cornetists in traditional jazz. Although influenced by Wild Bill, Tom had his own sound, played great lead, but could also take a ballad and make it a thing of beauty. Like Jake Hanna he also had a dry wit, entertaining audiences between numbers with jokes and amusing reminiscences. In fact he could have had a career as a stand-up comedian.

Tommy lived life to the full and we enjoyed many hours together. He had his faults, but always played hard, partied a lot – sometimes too much – and enjoyed life until it eventually caught up to him. We all loved him and those of us who were close to him also knew that under a gruff exterior he was a sensitive and caring man.

And what did Jake and Tom have in common? They were not only great players, they were great entertainers, who were immensely proud of their music, but never took themselves too seriously. They genuinely loved the music and always gave it their best shot. The world of jazz is diminished by the passing of these four great talents and my personal world has become smaller.

Jim Galloway is a saxophonist, band leader and the former artistic director of Toronto Downtown Jazz. He can be contacted at: jazz@thewholenote.com.