As serious music has become both more ardent and more accommodating over the past few decades, so has the definition of what constitutes a musical group or which instrument is appropriate for a solo session. One of the instruments that benefitted the most from this liberal attitude is the double bass. Freed from its singular function as a timekeeper in jazz or to suggest rumbling menace in so-called classical music, it has become the object of new experiments.

Solo bass recitals are no longer the novelty they once were, but some four-string explorers go even further, creating situations where multi basses play together. Take for instance Rotations (Evil Rabbit Records ERR21 evilrabbitrecords.eu). Operating as Sequoia, four double bass players – two Germans, one Italian and a Canadian, all based in Berlin – come up with eight-tracks that irrefutably demonstrate the qualities of a program based entirely on what can be created with acoustic bass. Acoustic sometimes has to be emphasized, because when Germans Meinrad Kneer and Klaus Kürvers, Italian Antonio Borghini and Canadian Miles Perkin fuse swabbed impulses on a track such as Lifts and Escalators the results resemble those created by electronic instruments. A block of coursing low-pitched tones, this sonic chiaroscuro still reveals separate timbre strata. Shaking and bouncing the tune reaches a crescendo of spinning attachments then downturns. Overall, interspaced with concise instances of jazz-like thumping, the CD exhibits all sorts of bass desires: staccato and languid, stentorian and shrill. The almost 16-minute Rotations for example isolates an assortment of expositions. While one bass duo creates a droning ostinato, another two make the upper reaches of their strings chirp and whistle. Interacting with tremolo slices, the final sound-image is that of a lively chicken coop with each fowl contributing distinctive notes. A similar divide exists on the final Passing By. Except here individual aggressive thrusts are layered from altissimo to basso, exhibiting mesmerizing strength within a mid-section of shrieking spiccato; and climaxing with a display of stentorian power that makes the 1812 Overture seem like a mild exposition.

Solo bass recitals are no longer the novelty they once were, but some four-string explorers go even further, creating situations where multi basses play together. Take for instance Rotations (Evil Rabbit Records ERR21 evilrabbitrecords.eu). Operating as Sequoia, four double bass players – two Germans, one Italian and a Canadian, all based in Berlin – come up with eight-tracks that irrefutably demonstrate the qualities of a program based entirely on what can be created with acoustic bass. Acoustic sometimes has to be emphasized, because when Germans Meinrad Kneer and Klaus Kürvers, Italian Antonio Borghini and Canadian Miles Perkin fuse swabbed impulses on a track such as Lifts and Escalators the results resemble those created by electronic instruments. A block of coursing low-pitched tones, this sonic chiaroscuro still reveals separate timbre strata. Shaking and bouncing the tune reaches a crescendo of spinning attachments then downturns. Overall, interspaced with concise instances of jazz-like thumping, the CD exhibits all sorts of bass desires: staccato and languid, stentorian and shrill. The almost 16-minute Rotations for example isolates an assortment of expositions. While one bass duo creates a droning ostinato, another two make the upper reaches of their strings chirp and whistle. Interacting with tremolo slices, the final sound-image is that of a lively chicken coop with each fowl contributing distinctive notes. A similar divide exists on the final Passing By. Except here individual aggressive thrusts are layered from altissimo to basso, exhibiting mesmerizing strength within a mid-section of shrieking spiccato; and climaxing with a display of stentorian power that makes the 1812 Overture seem like a mild exposition.

Rather than halving the number and breadth of sounds they produce with only two bull fiddles, Swiss duo Peter K. Frey and Daniel Studer range through expanded narratives on Zwirn: Live in München (Creative Sources CS 239 CD creativesourcesrec.com). Less bellicose than Sequoia’s frequently all-out attack, the two employ scordatura, retuning and detuning to create timbres that often sound less string sourced than horn resembling. This is particularly apparent during the first measures of Eins Punkt Zwei. Until a clear string pluck resonates, it sounds as if a reed duet is in progress. Although not shying away from decorating their interface with mellow tones and sparkling peeps, toughness isn’t neglected either. The concluding Drei subsides after mandolin-pitched strums; upwards-moving string tweaks and almost visual sparks fly between the two on Zwei Punkt Zwei; and there are sections of the introductory Eins Punkt Eins where it appears as if the two are not only creating novel rhythms by twisting strings near their instruments’ scrolls, but sounding as if they’re ripping apart the bass wood as they play. Zwei Punkt Eins is the track most illustrative of the relationship. Climaxing with a series of spiccato runs that eventually relax into a peaceful conclusion, intense excitement is first built up by combining scrubbed lowing, aviary-like chirps and string recoils.

Rather than halving the number and breadth of sounds they produce with only two bull fiddles, Swiss duo Peter K. Frey and Daniel Studer range through expanded narratives on Zwirn: Live in München (Creative Sources CS 239 CD creativesourcesrec.com). Less bellicose than Sequoia’s frequently all-out attack, the two employ scordatura, retuning and detuning to create timbres that often sound less string sourced than horn resembling. This is particularly apparent during the first measures of Eins Punkt Zwei. Until a clear string pluck resonates, it sounds as if a reed duet is in progress. Although not shying away from decorating their interface with mellow tones and sparkling peeps, toughness isn’t neglected either. The concluding Drei subsides after mandolin-pitched strums; upwards-moving string tweaks and almost visual sparks fly between the two on Zwei Punkt Zwei; and there are sections of the introductory Eins Punkt Eins where it appears as if the two are not only creating novel rhythms by twisting strings near their instruments’ scrolls, but sounding as if they’re ripping apart the bass wood as they play. Zwei Punkt Eins is the track most illustrative of the relationship. Climaxing with a series of spiccato runs that eventually relax into a peaceful conclusion, intense excitement is first built up by combining scrubbed lowing, aviary-like chirps and string recoils.

More linear, but just as inventive, Denmark’s Nils Davidsen fashions11 multi-textural solos utilizing a single gong plus two or three basses on some tracks. Although the multiple-bass narratives on Noget at glæde sig til (ILK Music 217 CD ilkmusic.com) may be overdubbed there’s no hint of artificiality. Blending upper register timbres with a reed player’s facility, for instance, Davidsen turns the three-bass Extraterrestrial Breakfast into a piquant repast of sharp and sour resonations. Creating a rhythmic continuum by vibrating the gong-like cymbal, the two-bass M/S Kissavik smartly concludes as arco and pizzicato lines harmonize. As for the two brief tracks featuring a single bass and a gong the sonorous gamelan-like vibrations provide unique accompaniment to relaxed pulsing. It’s not that additional instruments are needed either. Just Turn Green for example demonstrates Davidsen’s arpeggio-rich, guitar-like facility, while Woody unsurprisingly highlights tones that remain charming while sourced from the bass’ mid-range and much lower. Finally the bassist’s skillful proficiency with four strings allows him to negotiate the interlocking sequences that make up Osiris in 4 Parts. Slipping from melancholy spiccato, rugged double-stopping and melodic sprightliness, his fervor leads to sul tasto bowing concluding the piece with a beefed-up sonic landscape. The CD title translates as “something to look forward to,” which is awkward grammatically but musically apt.

More linear, but just as inventive, Denmark’s Nils Davidsen fashions11 multi-textural solos utilizing a single gong plus two or three basses on some tracks. Although the multiple-bass narratives on Noget at glæde sig til (ILK Music 217 CD ilkmusic.com) may be overdubbed there’s no hint of artificiality. Blending upper register timbres with a reed player’s facility, for instance, Davidsen turns the three-bass Extraterrestrial Breakfast into a piquant repast of sharp and sour resonations. Creating a rhythmic continuum by vibrating the gong-like cymbal, the two-bass M/S Kissavik smartly concludes as arco and pizzicato lines harmonize. As for the two brief tracks featuring a single bass and a gong the sonorous gamelan-like vibrations provide unique accompaniment to relaxed pulsing. It’s not that additional instruments are needed either. Just Turn Green for example demonstrates Davidsen’s arpeggio-rich, guitar-like facility, while Woody unsurprisingly highlights tones that remain charming while sourced from the bass’ mid-range and much lower. Finally the bassist’s skillful proficiency with four strings allows him to negotiate the interlocking sequences that make up Osiris in 4 Parts. Slipping from melancholy spiccato, rugged double-stopping and melodic sprightliness, his fervor leads to sul tasto bowing concluding the piece with a beefed-up sonic landscape. The CD title translates as “something to look forward to,” which is awkward grammatically but musically apt.

Another Danish, but Berlin-based, bull fiddler, Adam Pultz Melbye uses Gullet’s nine tracks (Barefoot Records BFREC032CD barefoot-records.com) to showcase his skills with only one double bass, one bow plus a stick placed horizontally among the strings. More a deft colourist than someone swabbing gouts of paint onto a musical canvas, with angled string-darting and mid-range rubs he creates gamelan-like peals and flute peeps. At the same time, comparing tracks such as Attempts at Relevance and Zossener credibly demonstrate how power can be present as much when microscopic bow pulls lead to splintered tones as with off-centre yet tough col legno pushes. Taken as a whole, Melbye’s arco and pizzicato facility on these tracks is reminiscent of that of a writer who has mastered the short story. Perhaps however his next exercise should involve extended tale-telling.

Another Danish, but Berlin-based, bull fiddler, Adam Pultz Melbye uses Gullet’s nine tracks (Barefoot Records BFREC032CD barefoot-records.com) to showcase his skills with only one double bass, one bow plus a stick placed horizontally among the strings. More a deft colourist than someone swabbing gouts of paint onto a musical canvas, with angled string-darting and mid-range rubs he creates gamelan-like peals and flute peeps. At the same time, comparing tracks such as Attempts at Relevance and Zossener credibly demonstrate how power can be present as much when microscopic bow pulls lead to splintered tones as with off-centre yet tough col legno pushes. Taken as a whole, Melbye’s arco and pizzicato facility on these tracks is reminiscent of that of a writer who has mastered the short story. Perhaps however his next exercise should involve extended tale-telling.

One double bassist unfazed by lengthy improvisations is Paris’ Benjamin Duboc. His St. James Infirmary CD (Improvising Beings ib22 improvising-beings.com), consists of only two tracks, both more than 20 minutes apiece: the title tune and Saint-Martin. Each delineates one side of his mercurial talent. St. James Infirmary Blues is a deconstruction and reassembling of the folk-blues classic. Sonorous and diffident, his unhurried bumps, crunches and resonations, shake out unique variations on the theme until corrosive string stops break through the coconut shell of variations to expose the flesh of the familiar melody. The resulting sequence matches poignancy and power. Saint-Martin is even more challenging. Separating motifs through interludes of staccato whistles and strident buzzes, perhaps the result of unique tuning, his multiphonic exposition can be as thick as that expressed by all four bassists in Sequoia. His elaboration of assorted pitches from widely separated parts of his string set make it appear as if more than one bassist is at work. Exhibiting a mastery of col legno smacks, his stentorian pacing showcases unique string textures which are subsequently pierced with dagger-sharp thrusts. Buzzing drones finally make common cause with sul ponticello shrills for a finale of satisfaction and relief.

One double bassist unfazed by lengthy improvisations is Paris’ Benjamin Duboc. His St. James Infirmary CD (Improvising Beings ib22 improvising-beings.com), consists of only two tracks, both more than 20 minutes apiece: the title tune and Saint-Martin. Each delineates one side of his mercurial talent. St. James Infirmary Blues is a deconstruction and reassembling of the folk-blues classic. Sonorous and diffident, his unhurried bumps, crunches and resonations, shake out unique variations on the theme until corrosive string stops break through the coconut shell of variations to expose the flesh of the familiar melody. The resulting sequence matches poignancy and power. Saint-Martin is even more challenging. Separating motifs through interludes of staccato whistles and strident buzzes, perhaps the result of unique tuning, his multiphonic exposition can be as thick as that expressed by all four bassists in Sequoia. His elaboration of assorted pitches from widely separated parts of his string set make it appear as if more than one bassist is at work. Exhibiting a mastery of col legno smacks, his stentorian pacing showcases unique string textures which are subsequently pierced with dagger-sharp thrusts. Buzzing drones finally make common cause with sul ponticello shrills for a finale of satisfaction and relief.

On their own or in multiples, the double bassists here confirm that any expression of bass desires is only limited by a player`s imagination.

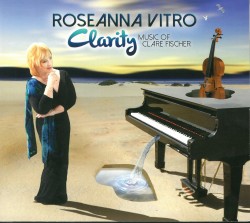

Clarity – Music of Clare Fischer

Clarity – Music of Clare Fischer