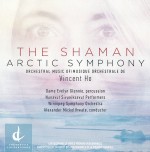

Several months ago in this column, in reference to Harry Freedman’s orchestral works, I noted that “I grew up understanding that what [identified] Canadian music as Canadian [were] aural landscapes reminiscent of the north, stark and angular, crisp and rugged, but at the same time lush and evocative.” I had that feeling again listening to The Shaman / Arctic Symphony – Orchestral Music of Vincent Ho (Centrediscs CMCCD 24317) featuring the Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra, of which Ho was the composer-in-residence between 2007 and 2014. The WSO performs both works under the direction of Alexander Mickelthwate. The Shaman is a percussion concerto written for Dame Evelyn Glennie who premiered it during the WSO’s New Music Festival in 2011, the performance recorded here. It is a stunning work, in the words of John Corigliano who wrote the Foreword to the booklet notes: “a work that set an atmosphere of magical stillness, with the soloist evoking unearthly sounds – wolf calls, shimmering colours, and the lightest of orchestral textures. [… In the second movement] Vincent has written a heavenly theme with almost no accompaniment by the orchestra. It goes to the heart, and is simple without ever being simple-minded. [… The final movement] grows into a primitive drum-led dance that is wild and relentless […] The Shaman should be played often!” Glowing praise indeed from one of the most significant mainstream American composers of our time.

Several months ago in this column, in reference to Harry Freedman’s orchestral works, I noted that “I grew up understanding that what [identified] Canadian music as Canadian [were] aural landscapes reminiscent of the north, stark and angular, crisp and rugged, but at the same time lush and evocative.” I had that feeling again listening to The Shaman / Arctic Symphony – Orchestral Music of Vincent Ho (Centrediscs CMCCD 24317) featuring the Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra, of which Ho was the composer-in-residence between 2007 and 2014. The WSO performs both works under the direction of Alexander Mickelthwate. The Shaman is a percussion concerto written for Dame Evelyn Glennie who premiered it during the WSO’s New Music Festival in 2011, the performance recorded here. It is a stunning work, in the words of John Corigliano who wrote the Foreword to the booklet notes: “a work that set an atmosphere of magical stillness, with the soloist evoking unearthly sounds – wolf calls, shimmering colours, and the lightest of orchestral textures. [… In the second movement] Vincent has written a heavenly theme with almost no accompaniment by the orchestra. It goes to the heart, and is simple without ever being simple-minded. [… The final movement] grows into a primitive drum-led dance that is wild and relentless […] The Shaman should be played often!” Glowing praise indeed from one of the most significant mainstream American composers of our time.

Although he is now an accomplished mid-career composer as his residencies (he is currently the artistic director of Calgary’s Land’s End Ensemble) and accolades testify, I can’t help thinking of Ho (b.1975) as a young composer. I first encountered his music in the summer of 1999 at the Strings of the Future workshop in Ottawa, where the iconic Arditti Quartet was reading through a number of fledgling works. Ho’s String Quartet No.1 made a lasting impression on me and went on to win a SOCAN Award. It was premiered during the November 2000 Massey Hall New Music Festival by the Composers Quartet. You can check it out on Soundcloud and judge for yourself.

At nearly 40 minutes, Ho’s Arctic Symphony is a mammoth, fully mature work. Written after a residency with the Circumpolar Flaw Lead System Study aboard the arctic research vessel CCGS Amundsen in 2008, the five-movement work is a dramatic depiction of Canada’s North and its Northern peoples. Ho writes of witnessing the interaction of scientists and Inuit elders as they shared valuable information about climate change and how it is affecting the culture and way of life in Indigenous communities. It opens with the haunting Prelude – Lamentations which starts with the eerie sounds of tundra winds and an Inuit welcome song performed by Nunavut Sivuniksavut Performers. As the song fades, the orchestra enters with a quiet shimmering cymbal and dark string textures reminiscent of that wind. Among the dramatic effects is an extended unison melody in the double basses juxtaposed with pointillist piano and interpolations from an extensive percussion battery. Three short, descriptively titled movements follow – Meditation, Aboard the Amundsen and Nightfall – during which Ho’s brilliant orchestration creates vivid pictures drawing on the full resources of the modern orchestra. Towards the end of the fourth movement however, all grows calm and a muted, vibrato-less solo strings chorale is heard, in the distance as it were, somewhat like the fleeting appearance of a theme from Death and the Maiden in George Crumb’s Black Angels for electric string quartet. The extended final movement O Glorious Arcticus – Postlude begins with quiet strings again but builds gradually to a rousing middle section, kind of a Northern take on Copland’s Rodeo or Weinzweig’s Barn Dance from The Red Ear of Corn. This too gradually passes as the work slows and diminishes, giving way to the sound of the wind again and the return of the Indigenous choir singing the joyous Inuit Sivuniksangat – The Future of Inuit by Sylvia Clouthier, the final lines of which are translated as “There is strength in who we are / We mustn’t forget that we are in this together.” A sentiment we would all do well to keep in mind.

These are two important additions to Canada’s orchestral repertoire and to paraphrase Corigliano, they should be played often. Kudos to Ho, to the WSO for recognizing and fostering his potential and to Centrediscs for a fabulous recording.

One of the perks of working at (my day job) New Music Concerts – beyond the privilege of daily contact with one of this nation’s foremost artists, Robert Aitken – is getting to meet some of the most brilliant minds in the field of contemporary music from around the world. Among my most cherished memories is the time spent with the late Elliott Carter (1908-2012) during several of his visits to Toronto, the last of which took place on the occasion of his 97th birthday. Arrangements were in place to bring him back five years later for a concert celebrating his 102nd, but a major snow storm in New York City curtailed his travel plans and we had to present the historic concert in Carter’s absence. On that occasion Carter’s associate Virgil Blackwell gave the very first performance of Concertino for bass clarinet and ensemble and Aitken gave the Canadian premiere of his Flute Concerto. Carter died in November 2012, just a month before his 104th birthday, and since that time New Music Concerts has presented one of his late works each December in honour of the iconic composer who took part in our concerts on seven occasions over the years.

And this brings me to a new Ondine release, Elliott Carter – Late Works (ODE 1296-2), which features among its titles several pieces presented by New Music Concerts in the past decade. Dialogues (2003) for piano and ensemble is here performed by pianist Pierre-Laurent Aimard with the Birmingham Contemporary Music Group, along with Epigrams (2012) for piano trio, which features Aimard with Isabelle Faust and Jean-Guihen Queyras. Aimard, a frequent Carter collaborator, is also featured with the Birmingham group in Dialogues II (2010) and, with percussionist Colin Currie, on Two Controversies and a Conversation (2011) for piano, percussion and chamber ensemble, plus Interventions (2007) and Soundings (2005) with the BBC Symphony Orchestra under Oliver Knussen’s direction. The brief orchestral work Instances, from Carter’s final year, completes the disc.

And this brings me to a new Ondine release, Elliott Carter – Late Works (ODE 1296-2), which features among its titles several pieces presented by New Music Concerts in the past decade. Dialogues (2003) for piano and ensemble is here performed by pianist Pierre-Laurent Aimard with the Birmingham Contemporary Music Group, along with Epigrams (2012) for piano trio, which features Aimard with Isabelle Faust and Jean-Guihen Queyras. Aimard, a frequent Carter collaborator, is also featured with the Birmingham group in Dialogues II (2010) and, with percussionist Colin Currie, on Two Controversies and a Conversation (2011) for piano, percussion and chamber ensemble, plus Interventions (2007) and Soundings (2005) with the BBC Symphony Orchestra under Oliver Knussen’s direction. The brief orchestral work Instances, from Carter’s final year, completes the disc.

In his later years, Carter’s music became a bit less craggy and unapproachable, although he never joined the ranks of “friendly music” composers. As Robert Aitken likes to say, good music “must challenge someone – the composer, the performer, the listener; preferably all three” and Carter’s music certainly continued to do that to the end. Back in 1990, before I joined the New Music Concerts team, I had the privilege of attending two rehearsals and a performance of the Canadian premiere of the String Quartet No.4 (1986) by Accordes. I was amazed that at each listening the work sounded unfamiliar, as if I had never heard it before. There were simply no touchstones for my relatively unsophisticated ears to grasp onto in the complexity of the score where seemingly each of the four parts moved independently.

As I say, there is no compromise in the late works, but somehow they do not seem as daunting. Perhaps it is my own development over the past two and a half decades, but I do think that the music itself also changed, becoming more genial and perhaps warmer. A case in point is the Two Controversies and a Conversation, which began as a single-movement concerto for piano and percussion, to which the two brief introductory movements were added at the invitation of Knussen. There is both playfulness and tension, harmony and discord. As the comprehensive notes by John Link tell us, “… from the final movement’s opening chords, the soloists quickly separate to engage in rapid fire exchanges with the orchestra and each other. The pianist proposes slow music, but is diverted by auto-horn-like blasts in the orchestra, which lead to a pianistic scherzando. Undaunted the piano returns to its rhapsodic music, speeding up and slowing down in long phrases that enact a would-be reconciliation […] The final gesture leaves the two conversationalists both far apart and exactly together.” This also happens time and again in my favourite piece on this disc, Epigrams, in 12 brief movements lasting just 14 minutes. I wonder if my comfort level is a result of having heard Stephen Sitarski, David Hetherington and Gregory Oh play it on a New Music Concert back in December 2014. Is it possible that Carter’s music can sound familiar after all? This new disc is a wonderful way to find out for yourself.

One of the loveliest World/pop-inflected discs to cross my desk in recent memory is Golpes y Flores by singer-songwriter Eliana Cuevas, who has made her home in Toronto for the last two decades. Released by Alma Records (ACD98172 almarecords.com), the disc is dedicated to her two daughters and her native country, Venezuela. Afro-Venezuelan rhythms permeate the entire project, which comprises seven Cuevas original tunes and three she co-wrote with producer/keyboardist Jeremy Ledbetter who also did the arrangements. Central to the recording is Yonathan “Morocho” Gavidia and several percussionist colleagues who Cuevas met through Aquiles Báez, a Venezuelan guitar-and-quatroist who performed in Toronto last year and who is also featured here on several tracks.

One of the loveliest World/pop-inflected discs to cross my desk in recent memory is Golpes y Flores by singer-songwriter Eliana Cuevas, who has made her home in Toronto for the last two decades. Released by Alma Records (ACD98172 almarecords.com), the disc is dedicated to her two daughters and her native country, Venezuela. Afro-Venezuelan rhythms permeate the entire project, which comprises seven Cuevas original tunes and three she co-wrote with producer/keyboardist Jeremy Ledbetter who also did the arrangements. Central to the recording is Yonathan “Morocho” Gavidia and several percussionist colleagues who Cuevas met through Aquiles Báez, a Venezuelan guitar-and-quatroist who performed in Toronto last year and who is also featured here on several tracks.

I confess I am at a disadvantage in that, although lyrics are included in the booklet, there are no translations and I don’t have much of a Spanish vocabulary. Fortunately the press release that accompanied my copy of the disc includes an explanation of the title. Cuevas says “‘Golpes’ means hit, often referring to rhythms, while ‘flores’ means flowers. To me, the title suggests a combination of the sophistication, beauty and gentleness of flowers and the strength and force of the Afro-Venezuelan rhythms.” There is one song in English, A Tear on the Ground, inspired by a visit to India, where Cuevas “spent a few days doing yoga at an ashram that was right by a lake that had a sign warning people to be careful of the crocodiles.” The song includes the lyric “crocodiles will swim in our tears / and our hearts will pound together without fear,” giving a new take on the phrase “crocodile tears.”

In addition to a number of Venezuelan musicians there are several familiar names from the local jazz scene including Mark Kelso, Rich Brown, George Koller and Daniel Stone. As mentioned, infectious rhythms abound and it’s hard to sit still while listening. One exception is the lush and lovely Mi Linda Maita inspired by Cuevas’ grandmother. With rich string sonorities and Cuevas’ pure voice it is breathtaking, but even here we end up swaying to the beat that builds as the song develops. Golpes y Flores, her fifth release, will further cement Cuevas’ place in Toronto’s World Music firmament and, I expect, will go a long way in bolstering her international career. It is a dandy!

Concert Note: The Eliana Cuevas Ensemble performs at the Rex, 198 Queen St. W. on January 4 and 5 at 9:30pm and at the Richard Bradshaw Amphitheatre at the Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts on January 10 (one set only at 5:30pm; free).

I will briefly mention one more pop-inspired disc that I’ve been enjoying this month, Let’s Groove: The Music of Earth, Wind & Fire, Cory Weeds’ latest venture on his Cellar Live label (CL041017 cellarlive.com). First off, I love the cover. I don’t know if it will come through in the miniature version shown here, but it’s worth a trip to the website just to check it out. I’m not sure it would be safe to “groove” in those oversized shoes, but it’s a great picture! The project was the brainchild of pianist and organist Mike LeDonne who did the arrangements of the iconic R&B band’s tunes and plays soulful and funky Hammond organ throughout. I was always a sucker for EWF vocal gymnastics, missed here, but the saxophones of Weeds (alto) and colleague Steve Kaldestad (tenor) are a satisfying substitute, especially their tight harmonies in unison passages and the flights of fancy in their solos. The excellent rhythm section includes LeDonne’s longtime associate drummer Jason Tiemann, percussionist Liam MacDonald and guitarist Dave Sikula. My favourites are the title track, Getaway and Shining Star. If you’re in the mood to Groove, you can’t top this.

I will briefly mention one more pop-inspired disc that I’ve been enjoying this month, Let’s Groove: The Music of Earth, Wind & Fire, Cory Weeds’ latest venture on his Cellar Live label (CL041017 cellarlive.com). First off, I love the cover. I don’t know if it will come through in the miniature version shown here, but it’s worth a trip to the website just to check it out. I’m not sure it would be safe to “groove” in those oversized shoes, but it’s a great picture! The project was the brainchild of pianist and organist Mike LeDonne who did the arrangements of the iconic R&B band’s tunes and plays soulful and funky Hammond organ throughout. I was always a sucker for EWF vocal gymnastics, missed here, but the saxophones of Weeds (alto) and colleague Steve Kaldestad (tenor) are a satisfying substitute, especially their tight harmonies in unison passages and the flights of fancy in their solos. The excellent rhythm section includes LeDonne’s longtime associate drummer Jason Tiemann, percussionist Liam MacDonald and guitarist Dave Sikula. My favourites are the title track, Getaway and Shining Star. If you’re in the mood to Groove, you can’t top this.

We welcome your feedback and invite submissions. CDs and comments should be sent to: DISCoveries, WholeNote Media Inc., The Centre for Social Innovation, 503 – 720 Bathurst St. Toronto ON M5S 2R4. We also encourage you to visit our website thewholenote.com where you can find enhanced reviews in the Listening Room with audio samples, upcoming performance details and direct links to performers, composers and record labels.

David Olds, DISCoveries Editor

discoveries@thewholenote.com

The Book of Transfigurations

The Book of Transfigurations