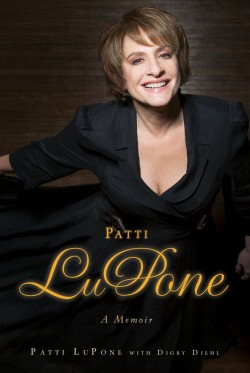

Patti Lupone: A Memoir By Patti Lupone with Digby Diehl

By Patti Lupone with Digby Diehl

Crown Archetype

336 pages, photos; $29.99

• During a show Patti Lupone gave in Toronto last year with Mandy Patinkin, she asked the audience to suggest a title for her upcoming memoirs. The title she ended up with, Patti Lupone: A Memoir, sounds decidedly low-key. That’s surprising, because there is nothing low-key about Lupone.

In her memoir Lupone is feisty, funny and daring – just as she is on stage. Notoriously combative, she is at the same time willing to expose vast layers of vulnerability. More than once while reading this, I wondered why she was sharing a particularly uncomfortable bit of information.

As she details her struggles for good parts, favourable contracts, and positive reviews, she writes, “I truly believe you learn more from failure than you do from success.” I found her descriptions of the never-ending struggles to get into a character especially interesting. But the one thing she has never had to struggle for is appreciation from audiences. In fact, her main battles seems to be with herself.

Lupone’s initial big-time success came with the premiere of Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Evita. But after premiering Webber’s Sunset Boulevard in London in 1992, she was dumped from the Broadway opening in favour of Glenn Close. Lupone was devastated – and evidently still is. It’s a messy story, with Webber as the duplicitous villain. But her career thrived with hit shows like Les Misérables, Sweeny Todd, and, most recently, Gypsy. Along the way there were small but special shows like her now-legendary Saturday midnight cabaret at a New York nightclub called Les Mouches while she was doing Evita on Broadway in 1980 (Ghostlight Records recently issued a live recording).

Webber gets top billing on her list of despised colleagues, but there’s also Bill Smitrovich, her co-star on a tv show she appeared in for four years, Life Goes On, and Chaim Topol, who was briefly – though none too briefly for her - her co-star in one of the many flops she was involved in, The Baker’s Wife. Her list of those she loves is much longer. It includes fellow Juilliard student and former boyfriend Kevin Kline, frequent co-star Patinkin, playwright David Mamet, teacher John Houseman, director Arthur Laurents, who wrote the book for Gypsy and directed her in it, and her husband Matt Johnston, who sounds like a remarkably balanced, supportive guy.

Lupone can sound either self-deprecating or self-serving – or both, even in the same sentence. But what always saves her here is her ability to find something wonderful in every experience, good or bad. That’s one of the many delights of this revealing and thoroughly enjoyable memoir. Conversational in style, it reads like an extended interview. In fact, Lupone has recorded it for an audio CD. I haven’t heard it, but I imagine it would be terrific to experience this memoir with Lupone’s spoken voice.

Evita is completing its run at the Stratford Festival with final performances on

November 1, 2, 4, and 5 at 2:00pm, and

November 6 at 8:00pm.