Listening habits blighted by COVID’s curse | No pleasure in solitary listening when it’s no longer a choice

As we enter into this extraordinary exercise in willed sensory deprivation that is our new reality (and how bizarre it is), I have found myself surprised by almost all of my reactions to the coronavirus. Not the least of which are my reactions to music. If I wanted to be rational about it, I would have to admit that while yes, I enjoy going to concerts, a good 90 per cent of the music I actually listen to – on the radio, online, from CDs, and files and even, heaven help me, on records – is still available to me. My listening habits really shouldn’t haven’t changed that much at all.

As we enter into this extraordinary exercise in willed sensory deprivation that is our new reality (and how bizarre it is), I have found myself surprised by almost all of my reactions to the coronavirus. Not the least of which are my reactions to music. If I wanted to be rational about it, I would have to admit that while yes, I enjoy going to concerts, a good 90 per cent of the music I actually listen to – on the radio, online, from CDs, and files and even, heaven help me, on records – is still available to me. My listening habits really shouldn’t haven’t changed that much at all.

And yet, they have. The musical impact on me of the coronavirus has been profound. Unexpectedly so.

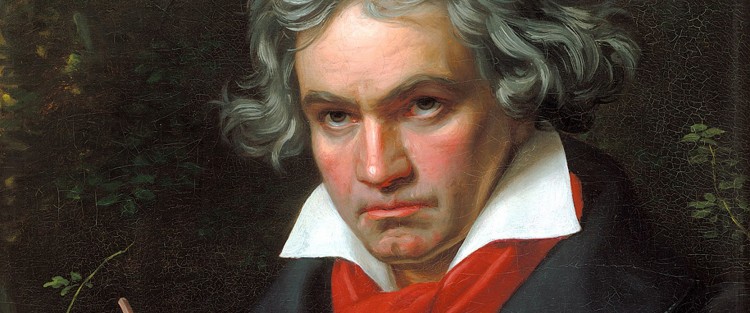

For one thing, I can hardly bear to listen to music at all these days. Not a note. I assume I’m in a tiny minority because COVID-19 playlists are popping up everywhere. I’ve tried listening to a few – I never get very far. I’m just not moved. Even some of my favourite composers are unbearable to me these days. Beethoven I find appalling. All that power and desperate projection of will strike me as completely wrong-headed these suffering days. Bach’s crystalline mathematical perfection likewise comes across, to me, as an utterly tone-deaf response to a world seemingly without ballast or divine balance. Who is left? Mozart, of course, to my mind the perfect coronavirus composer in his deeply ambiguous, but fundamentally loving relationship to the world. I just listened to the last act of Figaro the other day, which begins with that amazing G-minor Cavatina of Barbarina (my nominee for Mozart’s most underrated aria, right up there for the expression of pure grief with Pamina’s Ach, ich fühl’s, although Barbarina is lamenting the loss of a pin, not a lover) and ends with that extraordinary heaven-sent hymn to forgiveness (more religious than anything in the Requiem) that perfectly sums up Mozart’s fundamentally confused relationship to the world. That confusion, the combination of comedy and depth, farce and love, the unexpected breaking out of the purest feeling in the middle of nonsense is such a perfect reflection of our present state, except ours is one of horror, not farce, that I found myself, much to my surprise, awash in tears at opera’s end, weeping not just for the Countess – surely the most perfect, angelic creature in opera – but for us all.