The immovable reputation of Beethoven is the kind of continuity that either confirms the unchanging greatness of classical music, or makes us despair of the depth of its conventionality and inertness. I am old enough to remember the last time the world celebrated a major Beethoven anniversary, his 200th, in 1970. Fifty years later, just about everything in the world has changed, but Beethoven, it seems, has not.

The immovable reputation of Beethoven is the kind of continuity that either confirms the unchanging greatness of classical music, or makes us despair of the depth of its conventionality and inertness. I am old enough to remember the last time the world celebrated a major Beethoven anniversary, his 200th, in 1970. Fifty years later, just about everything in the world has changed, but Beethoven, it seems, has not.

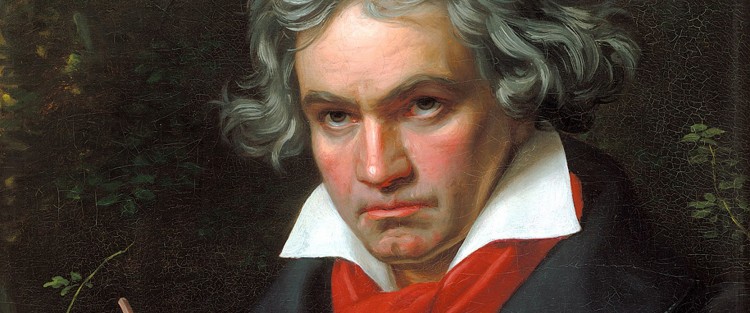

He still more or less bestrides our Western musical world like a colossus. People with no interest in or knowledge of classical music are still familiar with the da-da-da-dum of the Fifth Symphony or the transcendent Ode to Joy of the Ninth. They might even recognize the obsessive melancholy of Für Elise. For more serious music lovers, Beethoven remains the ne plus ultra.

How is it, though, that Beethoven can continue to perform the same ritualistic ceremonies for the Western mind as he has for a century, when the values Beethoven represents (of the Enlightenment and the French Revolution), are precisely the ones that have been reconsidered, put in play and found wanting in our contemporary world? Or so it seems. Just ask Stephen Miller, or Dominic Cummings, or Victor Orban, or even, if you can find him, Maxime Bernier. Not to mention, of course, He Who Shall Not Be Named. The decay of the Enlightenment values that Beethoven so completely represents is the central political reality of our times. Beethoven should be in disarray in this milieu. But he isn’t. Why not?

I think there are two reasons. The first is the most obvious – Beethoven speaks to us still because the world he rendered into sound continues to be, despite everything, the world we live in, or think we live in, or would like to think we live in. Beethoven was six when the Declaration of Independence was proclaimed, 17 when the Americans wrote the Constitution that is still dead-centre in their political discourse, 19 when the fall of the Bastille announced the French Revolution. The origins of the liberal democracy we still savour and try to defend were created during Beethoven’s youth, rendered into sound by him as an adult, and remained his guide throughout his life, long after they had been abandoned, tarnished and battered about by post-Napoleonic Europe. Today we know how complex and ambiguous those simplistic notions of liberty, equality and fraternity were, and are – but the fantasies they spin over us die a long and hard death. Beethoven has remained central to us because he allows us to revel in the glow of those myths, those truths and ideals that still inspire. Precisely these days, we need Beethoven to keep us together, to keep the fantasies spinning, to keep our better natures in play. Or so we think. Beethoven and the values he represents are the talismans we cling to as darkness creeps over the edges of our lives.

But there’s another, quite different, reason for Beethoven’s longevity, I think. A much more fundamental reason. And that has to do not with what Beethoven represents, but what he and his music are. Because one of the things about Beethoven’s music that is so obvious that it hardly bears saying (except that it is never said) is how simple, coarse and vulgar it is. Unparalleled really in Western music. Compared to virtually every other composer, Beethoven reeks of the street, of the tavern, of the visceral, of the elemental. Mozart is infinitely more sophisticated, Haydn more worldly and ironic, Chopin more cynical, Schumann more troubled, Wagner more manipulative – maybe only Mahler hints at Beethoven’s vulgarity, but Mahler toys with the vulgar so as to overcome it. Beethoven is different – he never strays far from the primal, obsessive ideas that make up so much of his music – the mindlessly simple triadic themes, the rhythmic compulsions, the brutal harmonic dissonances, the sheer towering ugliness of so much of his art. Beethoven struts his coarseness and vulgarity across the Western musical stage like a gang member, his banners and battle scars prominently on display. Cool enlightenment be damned – Beethoven is passion incarnate in music, not reason. But passion laced with intelligence – of the musically profound. Of the elemental. Of the basic. And that’s the key. That’s why he still speaks to us.

In his greatest moments, whipped into the Dionysian ecstasy of his Seventh Symphony, or the peace and serenity of the E-major variations of the 30th piano sonata, in the sardonic laughter of the metronomic Eighth Symphony, Beethoven takes us on a perilous journey that plays with his love of the precipice, of the precarious, of the primal. When Beethoven is inspired, the very bedrock simplicity of the music is the foundation for its astonishing success, fulfilling a promise of beauty in the world upon which we gambled when we made humankind the measure of everything (the true meaning of the Enlightenment). Beethoven is the artist of the challenge, the artist without a net, the artist lacking a stylistic tool kit with which he can spin out a few bars, or a few movements, or a few works. It’s always all or nothing with him. That’s why when Beethoven is at his best, there is nothing more thrilling in music. He takes on a challenge for us all, and prevails. On the other hand, when he is at his worst – in Wellington’s Victory or the King Stephen Overture or the listless, anemic “Emperor” Concerto, for example – nothing is more terrifying. It’s a glimpse into the abyss, a portrait of a man who stakes everything on himself, and fails. When Beethoven runs out of inspiration, there is nothing more empty in Western music.

It’s precisely because Beethoven offers the possibility of failure as well as success that makes his music so affecting and powerful. The simplicity of his language and his inability to hide behind any stylistic curtain raise the stakes of each composition. We’re always hanging in the balance with the composer as he tries to bust his way through each composition, setting impossible goals for himself and then trying to meet them (so that that obsessively repetitive rhythm of the Fifth Symphony doesn’t bore us, for example, or the sprawling architecture of the Third confuse). And that’s what makes Beethoven so modern. Because the modern world is Beethoven’s world – one where we have, in effect, made the same gamble on ourselves as he made in his music. A gamble on our ability to prevail, despite all, without ideological nets, without the safe harbours of convention, or race, nation, ethnicity or religion. A gamble on human reason and decency and strength.

Like the modern world, Beethoven is about precarity, about the perilous nature of being human when all the traditional sources of value have been pulled out from under us and there is nothing left but our own wits. He thrills us with his ability to set his own challenges, place himself in a stark, primal world of his own making, and successfully manage the fear and potential destruction that attend his every musical move. When he succeeds in navigating this landscape and delivers us safely home at a work’s conclusion, we celebrate ourselves in a manner unique in music, perhaps in all of art. Beethoven is the artist of the inner self, triumphant in the world. In that, he is supremely modern.

Robert Harris is a writer and broadcaster on music in all its forms. He is the former classical music critic of the Globe and Mail and the author of the Stratford Lectures and Song of a Nation: The Untold Story of O Canada.