Extended Interview with Andrew Timar

by Karen Ages

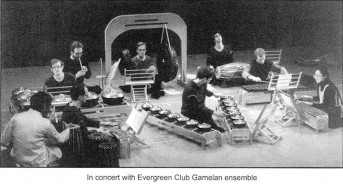

Anniversaries are a time to look back and reflect on time spent together, or on one's accomplishments over the years, and the Evergreen Club Contemporary Gamelan is doing just that. They celebrate their 25th anniversary season this month, with three different concerts: May 2 at the Open Ears Festival in Kitchener, and May 4 and 11 at the Music Gallery. I asked long-time member and suling player Andrew Timar to tell me a bit about the Ensemble and his role within it.

Andrew Timar: Jon Siddall founded the Evergreen Club, Canada's first gamelan, in 1983. We met while we were students at York University and became fast friends, performing extensively in various groups both in and out of school. Jon went on to do his graduate studies at Mills College, CA, studying composition with noted American composers Terry Riley, Lou Harrison and Robert Ashley. In addition, he studied gamelan degung at Mills with Lou Harrison (1917 - 2003), who was among the first Western composers to compose directly for entire gamelan (orchestra), as well as building several orchestras based on Indonesian gamelan from indigenous American materials. This Harrison connection established by Jon Siddall has proven significant for the future of ECCG for several reasons. The primary one is perhaps that Harrison assisted Siddall in acquiring his gamelan degung (or degung for short), which turned out to be Canada's first complete gamelan set. Jon now lives in Vancouver where he pursues his career as a composer, a CBC music producer, and teacher of degung music at the Vancouver Community College.

|

What is a “gamelan”, anyway? According to Andrew: The terminology can be confusing. The term 'gamelan' refers to several interlocking concepts: 1. A type of orchestra indigenous to certain regions of Indonesia; 2. the music made on a set of gamelan instruments; 3. also the group of musicians who play #2 on #1. |

As well as being an ensemble of 8 skilled young musicians, the original Evergreen Club was also a sort of composers' co-op too, dedicated to the creation of new works for degung. Many of the first generation of ECCG musicians were also composers who wrote music for our degung. In addition to Siddall, other composers who also performed with us in the early years included the American composer/musician Miguel Frasconi; percussionist/composer Mark Duggan; percussionist & now Ethnomusicologist Michael Bakan; pianist/musical sculptor/composer Gordon Monahan; and clarinetist/composer Robert W. Stevenson (currently Artistic Director of Array Music).

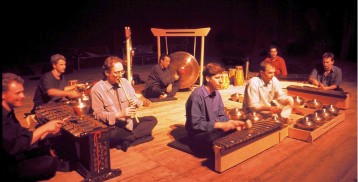

I would also add York University professor and mrdangam and kanjira maestro Trichy Sankaran, whom we commissioned on three separate occasions, and who performed with us as our guest. We can see him in the early ECCG photo (above) of our Dec. 1985 concert, which featured his invention, the mrdanga tarang, consisting of six tuned mrdanga (drums played primarily in the southern regions of India). The photo also shows several of the musicians I have just mentioned – and yes, that's a younger me playing the suling (bamboo ring flute) behind Bob Stevenson (on jengglong, the horizontal gong-chimes).

KA: How long have you been a member of the group?

AT: I was among the first composers commissioned to write for the group. My work North of Java (first draft, 1983) is also the title cut of our first disc, a vinyl LP - and also of our first CD. While ECCG's inaugural suling player was Ann McKeighan (now a CBC music producer), Jon Siddall invited me to take on suling duties from the second season (1984-5) onward. My learning curve was quite steep, since we had several difficult commissions to premiere, such as Trichy Sankaran's Svara Laya. Such demanding works came in quick succession. In addition, they had to be polished to a high performance level, since the national show Two New Hours on CBC radio was interested enough to pick up many of our concerts. From 1989 I served as the group’s Artistic Director for three seasons and have remained its sole suling player ever since. Blair Mackay, an in-demand percussionist, has been ECCG's able and longest-serving A.D. for over 18 years now.

KA: Where do the instruments come from, and how did they come to be here in Toronto?

AT: That's quite a story! Our first degung (set of instruments/type of gamelan) was made in West Java, the home of degung. It was given the name Si Pawit (In the Beginning) by the senior Bandung musician,

|

Many other notable musicians have performed with ECCG over the years. A very short list would include John Wyre of Nexus, Supernova string quartet, Nouvelle Ensemble Moderne, percussionist Beverley Johnston, mezzo-soprano Patricia O’Callaghan, Elmer Iseler Singers, the Sanctuary trio, Société de musique contemporaine du Québec, violin soloist Marc Fewer - and even the Aradia baroque ensemble.. |

choreographer and Sundanese cultural activist Enoch Atmadibrata, who organised their shipment to Toronto. Here again there’s a Lou Harrison connection. Lou had initially written to his friend Atmadibrata to introduce Siddall’s request for a degung. Our present degung was made in 1998-9 of the finest bronze by the noted gamelan maker Tentrem Sarwanto of Surakarta, Central Java. Several of us in ECCG made the memorable journey to his workshop to negotiate the instrumental range and tuning of our new degung. In the case of both degung, we took the unusual step of designing and crafting the "furniture" out of select Canadian hard maple lumber, on which the sounding parts of the instruments rest, right here in Southern Ontario. This combination of the best of Javanese gong forging resting on prime Canadian maple serves as an apt metaphor for the group’s multi-cultural aesthetic approach which respects the musical traditions of both cultures.

|

A note about the group's name: originally it was called Evergreen Club gamelan ensemble. Around ten years ago we changed it to Evergreen Club Contemporary Gamelan - or ECCG for short - in order to highlight our core repertoire of non-Indonesian contemporary compositions. In addition, the Indonesian word gamelan is a collective noun which includes the concept of collective music making, therefore it already incorporates the notion of 'ensemble' and 'orchestra', making the repetition of those terms redundant. |

KA: Was the original objective of ECCG to commission contemporary works, or did it start out as a traditional ensemble playing traditional works?

AT: Right from the beginning our focus was on the performance of contemporary Western compositions, many of which we wrote ourselves. In this respect we are quite different from most gamelan groups which now number in the hundreds and have spread to almost every continent. Most groups present music indigenous to the particular regional gamelan they play as their musical baseline and only later, if ever, look to their own culture for musical inspiration.

Why such a different approach for ECCG? For one thing, at that time there weren’t any other gamelans in the country, let alone gamelan teachers to study with. (We were real pioneers.) For another, the group’s leader and chief instructor Jon Siddall’s entry into the world of degung was via the American composer Lou Harrison, who himself had only relatively recently formally studied the Sundanese musical basis of degung. Siddall in turn did introduce a few lagu-laga degung klasik (traditional degung works) for ECCG to learn – but even these were in Harrison’s own ‘adapted’ versions using Western staff notation.

In 1993 we invited the Sundanese master suling soloist and multi-instrumentalist Burhan Sukarma to teach us degung repertoire and performance practice for six weeks. Several of us in ECCG have gone on to study the gamelan music performance of various sorts, as well as other Indonesian music genres.

KA: Can you tell me something about Evergreen's repertoire, both the contemporary compositions, and the traditional Sundanese pieces?

AT: The core corpus of Sundanese lagu-lagu degung klasik (musical canon of the gamelan degung) is about 50 – 60 works. This repertoire is not static, frozen into an unchanging “tradition”, however. While degung has its roots in the refined Sundanese court music heard by aristocrats and few other outsiders, over the past 50 years the genre has shown considerable vigour and has adapted to new social and political changes in its West Javanese homeland. This has been accomplished via new arrangements of pieces borrowed from other Sundanese music genres and through the infusion of new compositions which have trickled into this “degung canon”. In addition, older regional pieces have fallen out of favour and from living memory. Tagging this music with the single label ‘traditional’ therefore is problematic for me.

In fact, leading Indonesian degung groups have generally sought to expand the degung repertoire, performance styles, audience, and hopefully as a result, their own typically very modest musician incomes. They’ve done that by seeking ever new tunes, arrangements, and novel instrumental combinations. Furthermore, degung composers and arrangers have expanded the modal language of the music, introduced pre-composed tutti sections, and added hook-filled Sundanese lyrics set to catchy and sometimes complex vocal melodies. Recording companies have also exploited mass media such as radio, cassette, CD and VCD as an effective distribution vector for this music, enabling them to reach more listeners and consumers than at any other time in the music’s history.

|

Sundanese musicians do have a cipher notation (unrelated to staff notation) but since theirs is essentially an oral tradition, they never use it in practice or in performance. Using Western notation can introduce Western performance artifacts into the music of degung, and thus it is very rarely used in teaching or performing gamelan music, even in the West. |

The development of degung in its homeland, while particular in its individual profile and trajectory, is no different in aim from the music which is being made in other places in the world. In fact I feel ECCG is also following along a similar path, connecting in a meaningful way to our own local, regional and national audiences – but we do it with a decidedly Canadian accent. Regarding lagu-lagu degung klasik, ECCG has performed some dozen works over the years. Some of these have been released on our CDs: Solo, Artifact 027 (2002), and Sunda Song on Naxos 76061-2 CD (2004).

As for the other 90% of our repertoire, they are compositions which we have commissioned from Canadian, American, S. American and European composers. These include substantial works by two of the most important composers of 20th c. avant garde concert music: Lou Harrison and John Cage. Canadian composers such as Gilles Tremblay, Chan Ka Nin, James Tenney and Walter Boudreau, to name just a few, form the vast majority of our repertoire, however. We are particularly proud of our active commissioning policy, an essential part of our mandate, which has generated more than 150 compositions to date.

KA: When did you first become interested in the suling, and with whom did you study?

AT: Perhaps it was my woodwind playing background (I was a bassoonist and had also studied recorders and shawms at York University), which prepared me to be entranced by the sound of the suling. Most importantly, right from the start I could also imagine its ‘true voice’. I heard an elegant, eloquent, often melancholic mellismatic musical voice, despite the instrument’s simplicity (it’s made from a single internodal length of bamboo, without any mechanical keys to get in the way). Jon Siddall gave me my first suling pointers in 1983, though I must say that I learned essentially ‘on the job’, having to master the often challenging repertoire composers were writing for us, and performing in concerts, radio broadcasts and recordings. It was only in 1988 that I made my first trip to Indonesia, where I had two quite brief lessons on Sundanese suling.

My first series of intensive and extended suling lessons were with Burhan Sukarma, the foremost suling player of his generation. These took place in 1993 in Toronto, and then again several times later at his San Jose, CA home. I’ve found his playing to be among the most emotion- packed on any instrument I’ve ever heard, while his teaching style is extremely subtle and gentle if somewhat oblique, leaving much of the initiative up to the student. I also studied in Bandung, Indonesia with one of the leading suling player of the next generation, Endang Sukandar, who has recorded widely and is highly regarded.

Rounding off my Sundanese suling studies were two separate sessions in Toronto with the very talented multi-instrumentalist Yoyon Darsono, with whom I also studied tarompet (Sundanese oboe). My work with Yoyon had an unusual start. I received an invitation to report to a Toronto Beach area recording studio to meet the group that Yoyon was touring with. I hadn’t brought any of my sulings – I thought it was going to be a friendly ‘hang’. But no – it turned out that they wanted me to jam with them on suling with jazz guitarist Reg Schwager and pianist Ron Davis, no score, no rehearsal and with the mics on! The group was Krakatau and they later released an edited version of that live take on one of their CDs.

KA: Tell me something about the instrument itself. I know you've got quite a collection; what determines which suling you will use for any given concert or piece?

AT: The suling is technically a “ring flute" made of bamboo. Its ring is made of a strip of split bamboo tied artfully to the cut node at one end of the length of special species of bamboo. The ring and cut node form a channel to blow through. This sort of bamboo which the Sundanese call temiang has the right diameter to internodal length ratio range appropriate for suling; it grows straight and has the desired blond colour. In addition, its long internodal length means its bore doesn’t have to be drilled or shaped.

The suling is held vertically and blown at one end. While I have also taken lessons on the Balinese and Javanese sulings and have those in my collection of roughly 200, it’s the Sundanese varieties which I play most often in concert. There are a number of Sundanese types of suling, which are defined by length in centimeters, as well as by finger hole number and configuration. Staying with the suling sunda, I’ve commissioned a large series of sulings for a research project. They were custom made by the noted suling specialist maker Pak Toto in Bandung, in increments of approx. 2.5 cm, ranging from 29 cm to 80 cm.

There are primarily two types of suling used in degung. One has 6 finger holes (suling panjang, or suling tembang) and has a lower tonal range; the other has 4 finger holes (suling degung) and is shorter with a higher tonal range. The choice of which suling to use is sometimes given by the composer, or can otherwise be determined by the player taking into consideration the range of the melody, the density of the other instrumental parts, the genre from which it is derived, and whether there is a vocalist or not.

|

There is a further issue in choosing the appropriate suling for a specific gig: weather conditions and its effect on tuning. The most important factors here are humidity and ambient air temperature. This is a rather involved subject, but suffice it to say that when it is warm outside the humidity is also generally higher than when it is colder. All this affects the size of the bamboo suling’s core diameter and therefore its volume and pitch. To counteract this effect, I have several instruments on hand at all times, particularly when the weather is changing or when I am on tour. This precaution usually ensures that I have at least one suling in tune with the bronze instruments, which are much less sensitive to pitch variation due to atmospheric changes. |

KA: What concerts or special commission does ECCG have coming up, in celebration of its 25th anniversary?

AT: On Saturday, May 2, 2009, at 7:30 pm we'll be giving a concert at the Open Ears Festival, in Kitchener. Entitled "The Enduring Legacy of Lou Harrison”, it will feature several gamelan degung works by American composers Lou Harrison (1917-2003) and John Cage (1912-1992), both of whom were key figures in ECCG’s first decades. Cage’s Haikai was composed for ECCG, and is his only gamelan work. A world première of a new work by Gordon Monahan for prepared piano and ECCG rounds out this exciting bill.

On Monday, May 4, 2009, 8 pm at The Music Gallery, our programme is entitled “Suites from the Past”. ECCG will be joined by the eminent South Asian percussion master Trichy Sankaran performing on mrdangam for the world premiere of his Repercussions (2009). This is a suite of sections of works he has composed for ECCG, arranged by Bill Parsons. Our founding Artistic Director Jon Siddall will be joining us for the world premiere of his suite The Greenhouse Revisited (2009).

Our final Music Gallery concert is called “Sunda Songs”, Monday, May 11, at 8 pm. This event features ECCG's song repertoire, inspired by the Sundanese music of West Java, with guest divas Jennifer Moore, Suba Sankaran, and Maryem Tollar. The concert draws upon the group's Sundanese roots songbook and adds songs by Mark Duggan, by the Senegalese world music star Youssou NDour, and a rousing Palestinian folk song, all arranged by ECCG musicians.

The evening concert is preceded by a Hands-on Workshop, a rare, fun, free pre-concert event at 6:30 pm. The audience is invited to join members of the ECCG and our new community group Sora Priyangan to play our gamelan.

KA: And what's in store for the future? Any tours on the horizon?

AT: ECCG is completing the editing of our next CD, which we recorded with the Halifax-based Sanctuary trio. Last year we had great fun bringing the eminent Indonesian composer and musician Nano S. to work with us. We would certainly like to repeat that successful project, next year inviting another leading Sundanese musician. We will also be pursuing several educational outreach initiatives and will continue our Sora Priyangan community group.