Music and the Movies: Hot Docs 2018 Preview

![]() There are at least a dozen new films with a significant musical component in this year’s Hot Docs International Documentary Festival, which runs at various Toronto venues from April 26 to May 6 (hotdocs.ca). Many promising titles are tucked away among the 246 in the 2018 lineup, which celebrates the festival’s 25th anniversary. Among the ones I’ve seen, some are essential viewing and others are of more than passing interest.

There are at least a dozen new films with a significant musical component in this year’s Hot Docs International Documentary Festival, which runs at various Toronto venues from April 26 to May 6 (hotdocs.ca). Many promising titles are tucked away among the 246 in the 2018 lineup, which celebrates the festival’s 25th anniversary. Among the ones I’ve seen, some are essential viewing and others are of more than passing interest.

Gurrumul: April 28, 29, May 5. Paul Damien Williams’ definitive portrait of Geoffrey Gurrumul Yunupingu, the blind-from-birth Indigenous singer from Echo Island in Arnhem Land, Australian Northern Territory, manages the difficult task of fusing the artistic and personal life of one of the most significant musicians Australia has ever produced. “I am my ancestors,” Gurrumul says of his songs, most of which are in the language of his Guratj community whose musical traditions go back thousands of years. With hours of performance and rehearsal footage to choose from, Williams chronicles Gurrumul’s musical ascendancy from when he was discovered by Mark Grose (who became his manager) and Michael Hohnen (who became his producer and “brother”). Hohnen accompanied him on the double bass on tour and recordings; their two-decades-long relationship ended with Gurrumul’s death in 2017 at the age of 46. Gurrumul’s soulful tenor voice was a powerful musical instrument; once you’ve heard it, it’s not easily forgotten. Neither is Williams’ film.

Gurrumul: April 28, 29, May 5. Paul Damien Williams’ definitive portrait of Geoffrey Gurrumul Yunupingu, the blind-from-birth Indigenous singer from Echo Island in Arnhem Land, Australian Northern Territory, manages the difficult task of fusing the artistic and personal life of one of the most significant musicians Australia has ever produced. “I am my ancestors,” Gurrumul says of his songs, most of which are in the language of his Guratj community whose musical traditions go back thousands of years. With hours of performance and rehearsal footage to choose from, Williams chronicles Gurrumul’s musical ascendancy from when he was discovered by Mark Grose (who became his manager) and Michael Hohnen (who became his producer and “brother”). Hohnen accompanied him on the double bass on tour and recordings; their two-decades-long relationship ended with Gurrumul’s death in 2017 at the age of 46. Gurrumul’s soulful tenor voice was a powerful musical instrument; once you’ve heard it, it’s not easily forgotten. Neither is Williams’ film.

The Artist & the Pervert (April 27, 29, May 4) is a no-holds-barred look at the personal and professional life of Georg Friedrich Haas, one of the major European composers of his generation. His best-known work, In Vain (2000), was written in response to the rise of the Austrian far-right Freedom Party. Simon Rattle, one of the film’s talking heads, calls it “a really astonishing work of art … that audiences can’t get enough of.” As a child in Austria Haas was beaten by his Nazi parents. At 20 he resolved to rid himself of their “venomous ideas.” At 50 he had his first BDSM relationship, finally giving in to his urge to dominate. Three years ago the 60-ish Haas, by then a New Yorker, married his soulmate and muse, Mollena Williams-Haas, an African-American kink educator and bawdy storyteller with whom he has a loving 24/7 master/slave relationship. “I can now work much more intensively and more focused than before,” he says. An intimate examination of the process of making music itself, The Artist & the Pervert is an idiosyncratic introduction to Haas’ floating constellations of overtones and microtonal experimentation.

The Artist & the Pervert (April 27, 29, May 4) is a no-holds-barred look at the personal and professional life of Georg Friedrich Haas, one of the major European composers of his generation. His best-known work, In Vain (2000), was written in response to the rise of the Austrian far-right Freedom Party. Simon Rattle, one of the film’s talking heads, calls it “a really astonishing work of art … that audiences can’t get enough of.” As a child in Austria Haas was beaten by his Nazi parents. At 20 he resolved to rid himself of their “venomous ideas.” At 50 he had his first BDSM relationship, finally giving in to his urge to dominate. Three years ago the 60-ish Haas, by then a New Yorker, married his soulmate and muse, Mollena Williams-Haas, an African-American kink educator and bawdy storyteller with whom he has a loving 24/7 master/slave relationship. “I can now work much more intensively and more focused than before,” he says. An intimate examination of the process of making music itself, The Artist & the Pervert is an idiosyncratic introduction to Haas’ floating constellations of overtones and microtonal experimentation.

I Used To Be Normal: A Boyband Fangirl Story: world premiere April 26, 27, May 4, 6. Three generations of women (two Australian and two American), 18 to 64, share their obsessions with The Beatles, Take That, the Backstreet Boys and One Direction. If you’ve ever wondered why teenage girls scream at concerts (“It was so cathartic”), you’ve come to the right place. Taking us inside the mindset of these obsessed boyband fangirls (“They’re just like Barbie Dolls; they’re so perfect; they’re all my boyfriends”), the film is seeded with retro footage and pop candy songs. Spoiler alert: there is no music by The Beatles in this film.

Bathtubs Over Broadway: May 1, 3, 5. Steve Young, a comedy writer for the Late Show with David Letterman, stumbled onto a few vintage record albums – bizarre cast recordings marked “internal use only” – that were full-throated Broadway-style musicals whose subjects were the products of corporate America: General Electric, McDonald’s, Ford, DuPont, Xerox – Everything’s Coming up Citgo, for example. Bathtubs over Broadway follows Young deeper down the rabbit hole of this most unusual musical genre. With David Letterman, Chita Rivera, Martin Short, Florence Henderson, Susan Stroman, Jello Biafra and more. Co-presented by the Musical Stage Company.

Barbara Rubin and the Exploding NY Underground: May 2, 4, 5. Barbara Rubin was a teenage experimental filmmaker, whose transgressive film Christmas on Earth caused a sensation when it screened in NYC in 1964. She hung out with Bob Dylan and Allen Ginsberg and (with Factory habitué Gerard Malanga) introduced Andy Warhol to the Velvet Underground. Rubin was a spoke in the avant-garde wheel for more than 15 minutes; Warhol shot her screen test in 1965. Yet within a few years she had become a Hasidic Jew and moved to a religious community in France, dying there at 35. Her lifelong friend, legendary experimental filmmaker and curator Jonas Mekas, saved all her correspondence. That and contemporaneous film footage were the fodder for Chuck Smith’s fascinating cultural touchstone; music by Sonic Youth’s Lee Renaldo.

Barbara Rubin and the Exploding NY Underground: May 2, 4, 5. Barbara Rubin was a teenage experimental filmmaker, whose transgressive film Christmas on Earth caused a sensation when it screened in NYC in 1964. She hung out with Bob Dylan and Allen Ginsberg and (with Factory habitué Gerard Malanga) introduced Andy Warhol to the Velvet Underground. Rubin was a spoke in the avant-garde wheel for more than 15 minutes; Warhol shot her screen test in 1965. Yet within a few years she had become a Hasidic Jew and moved to a religious community in France, dying there at 35. Her lifelong friend, legendary experimental filmmaker and curator Jonas Mekas, saved all her correspondence. That and contemporaneous film footage were the fodder for Chuck Smith’s fascinating cultural touchstone; music by Sonic Youth’s Lee Renaldo.

Bachman: world premiere May 2, 3, 4. Randy Bachman’s American Woman was a chartbuster for the Guess Who and You Ain’t Seen Nothin’ Yet also hit number one for Bachman-Turner Overdrive, but the Winnipeg native is at least as well known for Randy Bachman’s Vinyl Tap on CBC Radio One. Each week Bachman fills two hours of thematically unified airtime with music and anecdotes delivered matter-of-factly, intimately and authoritatively. John Barnard profiles the man and his craft.

Matangi/Maya/M.I.A (May 3, 5, 6) follows Sri Lankan genre-bending music star M.I.A. Mathangi Arulpragasam. “This is not a normal pop documentary, because M.I.A. was not a normal pop star,” writes Spencer Kornhaber in The Atlantic. The Strange Sound of Happiness (April 30, May 2) tells the director’s own story of how his obsession with the marranzano (jaw harp) led him from Sicily to Yakutia in Siberia to study under the legendary master of the instrument. Could it have been Sergio Leone’s memorable use of the instrument in For a Few Dollars More that triggered director Diego Pascal Panarello’s dream?

My Father Is My Mother’s Brother: May 2, 3. Tolik, an artist in the Ukrainian underground music scene, is raising his niece while her mother is in and out of a psychiatric hospital. “The film seems to float, like the melody of one of Tolik’s songs,” according to Céline Guénot of the Nyon, Switzerland documentary film festival. To Want, To Need, To Love: May 2, 4. Two actor/musicians and the director’s brother are part of a troupe of artists, travelling from Zurich to Belgrade to Pristina, who create musical performance pieces around the question “What do you believe in?” Music by Kosovo native Arbër Salihu, who also plays one of the principal roles.

My Father Is My Mother’s Brother: May 2, 3. Tolik, an artist in the Ukrainian underground music scene, is raising his niece while her mother is in and out of a psychiatric hospital. “The film seems to float, like the melody of one of Tolik’s songs,” according to Céline Guénot of the Nyon, Switzerland documentary film festival. To Want, To Need, To Love: May 2, 4. Two actor/musicians and the director’s brother are part of a troupe of artists, travelling from Zurich to Belgrade to Pristina, who create musical performance pieces around the question “What do you believe in?” Music by Kosovo native Arbër Salihu, who also plays one of the principal roles.

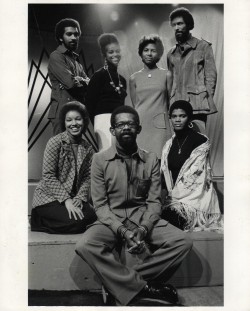

Mr. SOUL!: April 27, 28, May 5. A who’s who of black musical legends of the 1960s appeared on the PBS variety show SOUL from 1968 to 1973. Rare archival footage of the era dovetails with an intimate portrait of Ellis Haizlip, the openly gay producer-turned-host who is the film’s eponymous subject. Sidney Poitier, James Baldwin, Toni Morrison and Muhammad Ali, among others, also lend their voices to this moment of American cultural history. United Skates: April 28, 30, May 4. The roller rink scene and the Black community go under the microscope through the eyes of three skaters from LA, Chicago and North Carolina, as what was once a little-known cultural phenomenon and incubator of such hip-hop stars as N.W.A. and Queen Latifah fights to survive racism and a new economic reality. Jongnic (JB) Bontemps’ score was recorded by the Macedonian Symphonic Orchestra just last month.

Mr. SOUL!: April 27, 28, May 5. A who’s who of black musical legends of the 1960s appeared on the PBS variety show SOUL from 1968 to 1973. Rare archival footage of the era dovetails with an intimate portrait of Ellis Haizlip, the openly gay producer-turned-host who is the film’s eponymous subject. Sidney Poitier, James Baldwin, Toni Morrison and Muhammad Ali, among others, also lend their voices to this moment of American cultural history. United Skates: April 28, 30, May 4. The roller rink scene and the Black community go under the microscope through the eyes of three skaters from LA, Chicago and North Carolina, as what was once a little-known cultural phenomenon and incubator of such hip-hop stars as N.W.A. and Queen Latifah fights to survive racism and a new economic reality. Jongnic (JB) Bontemps’ score was recorded by the Macedonian Symphonic Orchestra just last month.

Believer (May 1, 3, 4) follows Imagine Dragons’ frontman Dan Reynolds and openly gay former Mormon Tyler Glenn, lead singer of Neon Trees, as they create LoveLoud, a music and spoken-word festival designed to spark dialogue between the Mormon church and members of the LGBTQ community. Love, Scott (April 28, 29, May 3) follows Scott Jones, a gay musician oparalyzed from the waist down by a homophobic stabbing attack, as he rebuilds his life, in part through working with choirs. Score by Sigur Rós!

Among the films by Hot Docs’ 2018 Outstanding Achievement Award recipient Barbara Kopple are The Dixie Chicks: Shut Up and Sing (May 1), a fly-on-the-wall chronicle of how the popular alt-country band dealt with the fallout from lead singer Natalie Maines’ criticism of President George W. Bush and his Iraq war policy; and Miss Sharon Jones! (May 2), Kopple’s inspirational portrait of the legendary soul singer that celebrates her music-making, joyful spirit and determination to carry on despite the cancer diagnosis that would take her life. May 3, Kopple will introduce a surprise screening of My Generation (2000), which takes a star-studded musical trip across three Woodstock Festivals (1969, 1992 and 1999) to see just how things have changed (or not).

Included in the Redux program, ”a retrospective showcase of documentaries that deserve another outing on the big screen,” is A Drummer’s Dream (2010) on May 2, featuring Nasyr Abdul Al-Khabyyr, Dennis Chambers, Kenwood Dennard, Horacio "El Negro" Hernandez, Giovanni Hidalgo, Mike Mangini and Raul Rekow. Finally, Focus On John Walker – a retrospective of the Canadian filmmaker’s work – includes Men of the Deeps (2003) on May 5, about a world-renowned choir of working and retired coal miners who sing passionately about lives spent deep underground as the last coal mine in Cape Breton prepares to close.

Hot Docs International Documentary Film Festival plays April 26 to May 6 in various locations throughout Toronto. See hotdocs.ca for further information.

Paul Ennis is the managing editor of The WholeNote.