Two brilliant young European violinists make their local debuts in February. In winning the 2001 Queen Elizabeth Competition, Latvian violinist Baiba Skride joined such luminaries as Oistrakh, Kogan, Laredo and Repin in the fiddling firmament. The Guardian recently called Skride “a passionate heart-on-sleeve player.” Now 34, she will appear with the TSO in Brahms’ richly sonorous Violin Concerto, February 17 and 18.

Two brilliant young European violinists make their local debuts in February. In winning the 2001 Queen Elizabeth Competition, Latvian violinist Baiba Skride joined such luminaries as Oistrakh, Kogan, Laredo and Repin in the fiddling firmament. The Guardian recently called Skride “a passionate heart-on-sleeve player.” Now 34, she will appear with the TSO in Brahms’ richly sonorous Violin Concerto, February 17 and 18.

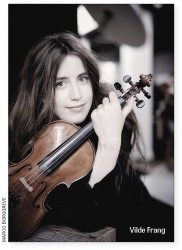

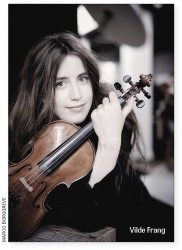

According to BBC Music Magazine, the 29-year-old Norwegian, Vilde Frang, “has the knack of breathing life into every note.” Frang will give a recital at Koerner Hall, March 2, with Michail Lifits on piano. Her program begins with Schubert’s Fantasy in C Major for Violin and Piano D934, another masterpiece from the last year of the composer’s life, and moves through Lutoslawski’s Partita, commissioned by Pinchas Zukerman in 1985, before concluding with Fauré’s ever-popular Violin Sonata No.1. Frang began her musical education at four, played Sarasate’s Carmen Fantasy with the Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by Mariss Jansons, when she was barely 13, and was thrust into the limelight when she was named Credit Suisse Young Artist of the Year in 2012. A recording contract and worldwide touring were the result.

It’s illuminating to hear both violinists talking about inspiration and interpretation in interviews readily available in cyberspace. Skride told Tobias Fischer (on Tokafi.com April 20, 2006) that interpretation “means giving my opinion to the audience, while at the same time respecting what the composer might have wanted. It’s a combination of my personal beliefs and the composer’s probable intent.” Her interpretive process, she continued, is “almost always emotional. Of course, there are certain things you have to know about and naturally you do get your facts straight while preparing. But 99 percent is intuition, absolutely.” Her approach to performing live is “simply giving everything you have in that very moment.”

In a YouTube video biography made shortly after her Credit Suisse honour, while soaring on her violin in rehearsal for Bruch’s Violin Concerto No.1 with Jakub Hrůša and the Philharmonia Orchestra, Frang spoke of the importance she places on trusting her instincts, how it’s crucial to take in things and let yourself be inspired. “Inspiration is really the most important thing,” she said. “I use my instrument as a tool [to transform inspiration]. Whether you hear Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, a wonderful horn solo or the sound of the sea, it’s something you can actually work with.”

Later that year, on August 1, 2012, Frang spoke with Laurie Niles of violinist.com about what brought her to the violin. “My father is a double bass player, and my sister is also a double bass player – my mother isn’t a musician, actually. But I watched my sister play in youth orchestras, when I was small, and obviously I thought I was the next one in line, in the double basses family! To me it was a natural thing, but then my father made this argument: our family had a Volkswagen, which was a very tiny car. He said, ‘Can you imagine, when we go on holiday, with three double basses? There is no chance the whole family will get space in the car!’

“So he made me a smaller instrument. It was made of cardboard – there were no strings on it. So I could put my Little Twin Star stickers on it, and Hello Kitty stickers – but the fact that it didn’t make any sound – I found this to be very frustrating! I had to ‘play’ on it for almost a year until I finally got a violin which was alive, which made sound.

“I remember the moment I got the violin that was real, that was really living and alive – I’ve never practised so inspired in all my life, as I did the first couple of days with that violin! I was in seventh heaven, I was so happy.”

Niles asked Frang, who began with the Suzuki method, how she connected with Anne-Sophie Mutter (See my November 2014 column in The WholeNote for more on Mutter and her foundation): “I first played for Anne-Sophie Mutter when I was 11-years-old,” she said. “After that, she asked me to keep her updated, and she followed my development. I kept sending her recordings and tapes of my playing, and letters about how I was doing. It was obviously a very inspirational thing for me, because I knew that she was always there watching, somewhere. When I was 15, she invited me to Munich to audition for her again, and then I was taken into her foundation, her Freundeskreis Stiftung, or Circle of Friends Foundation, and I was also given this Vuillaume instrument.

“Ms. Mutter has also been a great, great mentor to me over all these years. I did a tour with her in 2008, and we played in Carnegie Hall and the Kennedy Center in Washington. I played the Bach Double with her. Of course, I learned a lot from this experience, not only playing for her, but playing with her. I think the most important was that she encouraged me to always trust my own instincts and follow my own voice. That is her top priority, and that’s the message she wanted to give, which I think is a wonderful thing.

“But more than any other musician I know, she is extremely focused on exploring the musical score, in order to get as close as possible to the composer. Many people might consider her to be very free, but actually she has the most authentic and strictest approach that I know of. I think that is why she allows herself to have that amount of freedom. The more you know the piece and the better you know the score, the more freedom you actually have yourself.”

Hamelin past and future. Marc-André Hamelin’s Music Toronto recital on January 5 had a blissful component running through it from Liszt’s Bénédiction de Dieu dans la solitude to the Schubert Sonata in B-flat D960 and the well-chosen encore, Messiaen’s Prelude “The Dove.” For me, this emotional line reached its apex with the sublime second movement of the Schubert which had a profundity that reminded me of the last three Beethoven sonatas. There was a serenity to Hamelin’s playing that was more pronounced than when he played at Koerner Hall the previous March. At times he seemed to slow the music just enough that you could feel it palpably.

During the conversation I had with him in November (see my article in the December 2015-January 2016 issue of The WholeNote), Hamelin described his relationship with Mendelssohn’s Piano Concerto No.1, which he will perform with the TSO on February 25 and 27. “I learned it very early,” he told me. “I remember the first time I played it was with Skrowaczewski and the Montreal Symphony. I believe it was somewhere like 1990 or ’91. It’s certainly not the deepest piece ever written but it shows consummate craftsmanship. And it’s also very entertaining for audiences. And in some ways quite touching.” Louis Langrée, famous for his stewardship of the Mostly Mozart Festival, his career blossoming as music director of the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, will conduct.

Quick Picks

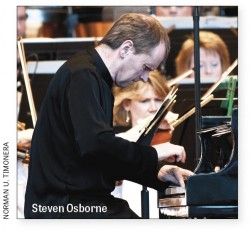

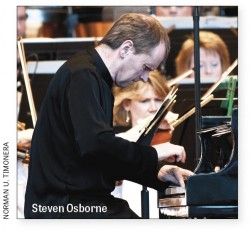

Feb 4 The last time I heard the Annex Quartet, they showed their sensitive musicianship supporting Jan Lisiecki in the chamber versions of Beethoven’s Piano Concertos Nos. 2 and 4. Their solid Music Toronto recital includes string quartets by Janáček, R. Murray Schafer and Mendelssohn. Feb 18 The irrepressible St. Lawrence String Quartet makes its annual visit to Music Toronto with works by Haydn, Samuel Adams and Schumann. Mar 1 The distinguished British pianist Steven Osborne performs two Schubert Impromptus D935 (fresh from his sparkling new Schubert CD) and a selection of Debussy and Rachmaninoff, in his Music Toronto return.

Feb 4 The last time I heard the Annex Quartet, they showed their sensitive musicianship supporting Jan Lisiecki in the chamber versions of Beethoven’s Piano Concertos Nos. 2 and 4. Their solid Music Toronto recital includes string quartets by Janáček, R. Murray Schafer and Mendelssohn. Feb 18 The irrepressible St. Lawrence String Quartet makes its annual visit to Music Toronto with works by Haydn, Samuel Adams and Schumann. Mar 1 The distinguished British pianist Steven Osborne performs two Schubert Impromptus D935 (fresh from his sparkling new Schubert CD) and a selection of Debussy and Rachmaninoff, in his Music Toronto return.

Feb 5 Conductor Eric Paetkau’s contagious energy and musicianship guide the eclectic group of 27 in Finzi’s bucolic A Severn Rhapsody and a trio of French works including Dubois’ Cavatine for Horn featuring the TSO’s Gabe Radford. The dynamic Nadina Mackie Jackson is the bassoon soloist in the world premiere of Paul Frehner’s Apollo X.

Feb 11 An ingenious piece of animation, The Triplets of Belleville is filled with cultural references that fly by with terrific panache, Sylvain Chomet’s 2003 film has rightly become a classic. Composer Benoît Charest leads Le Terrible Orchestre de Belleville and special guest Nellie McKay in the live performance of his infectious, original score for the film (rooted in 1930s vaudeville/jazz) accompanying this special screening at Roy Thomson Hall.

Feb 12 Cellist Rachel Mercer follows up her well-received CD of Bach’s unaccompanied cello suites with an exciting concert of music for solo cello at Gallery 345, beginning with one of those Bach suites. Mercer then moves from Cassadó’s early 20th century suite to contemporary pieces by Andrew Downing and the world premiere of Darren Sigesmund’s Solo Suite.

Feb 13 Celebrate the Year of the Monkey with the TSO as the great violinist Maxim Vengerov is the soloist in the Butterfly Lovers Concerto. Long Yu, artistic director of the China Philharmonic Orchestra and music director of the Shanghai Symphony Orchestra, conducts. Feb 22 The Associates of the TSO present works by Françaix, Janáček and Brahms for various combinations of flute, oboe, horn, bassoon and two clarinets. Mar 2 Seven soloists from the TSO’s ranks (including the ubiquitous Teng Li) showcase their talents when the TSO presents music by Paganini, Vivaldi and Haydn (his elegant and tuneful Sinfonia Concertante in B-flat Major for the unusual combination of soloists, violin, cello, oboe and bassoon).

Feb 17 The hip, Brooklyn-based orchestral collective, The Knights, make their Koerner Hall debut, joined by violinist Gil Shaham, whose warm playing should illuminate Prokofiev’s Violin Concerto No.2, in all its angularity and dark beauty. Feb 26 Koerner Hall gives us the rare gift of hearing violinist Christian Tetzlaff, his sister, cellist Tanja Tetzlaff and pianist Lars Vogt performing piano trios by Schumann, Dvořák and Brahms. Richard Haskell praised them in these pages last September for their “conducive music-making in the three Brahms piano trios.” Andras Schiff’s monumental Feb 28 recital in Koerner Hall is sold out. Those lucky enough to have tickets (myself included) can look forward to a program memorable for its inclusion of the final piano sonatas by Haydn, Beethoven, Mozart and Schubert. Mar 4 Much-in-demand (especially since she received the Avery Fisher Career Grant in 2008) Canadian violinist, Karen Gomyo, teams up with well-regarded cellist, Christian Poltéra, and talented young Finnish pianist, Juho Pohjonen, to perform trios and sonatas by Haydn, Janáček and Dvořák. All four of these events are presented by the Royal Conservatory.

Feb 19 The charming Trio Arkel (TSO members violist Teng Li and cellist Winona Zelenka, COC concertmaster Marie Bérard) move into their new venue, Jeanne Lamon Hall at Trinity-St. Paul’s Centre, with a program including Gubaidulina’s exhilarating String Trio, Kodály’s Serenade for Two Violins and Viola and Beethoven’s glorious Quintet for Strings, Op.29 “The Storm.” Joining them for this and a repeat concert in London, Feb 29, presented by the UWO Don Wright Faculty of Music, will be violinist Scott St. John and violist Sharon Wei.

Feb 20 Also in London, Jeffery Concerts presents the award-winning cellist Yegor Dyachkov and longtime chamber music partner, pianist Jean Saulnier, in works by Brahms, Schumann and Janáček.

Feb 23 Charles Richard-Hamelin, who finished second in last year’s prestigious Chopin competition in Warsaw, will give a COC free noon-hour concert of a selection of Chopin’s last piano works at the Richard Bradshaw Amphitheatre. Based on his thrilling performance of Chopin’s Sonata No.3 at Mazzoleni Hall on January 15, I urge you not to miss it.

Mar 3 The Women’s Musical Club of Toronto’s talent-laden season continues with the widely acclaimed Daedalus String Quartet performing Sibelius’ String Quartet in D Minor “Voces Intimae” Op.56. Montreal native, clarinetist Romie de Guise-Langlois, joins them in James MacMillan’s powerful lament, Tuireadh, and Brahms’ sublime Clarinet Quintet in B Minor Op.115.

Paul Ennis is the managing editor of The WholeNote.

Artie Roth once said to me – and I’m paraphrasing – that the drummer is the encyclopedia of the ensemble, the player who knows the repertoire most intimately, who can most immediately call up what happened on this chorus of that recording in Febtober of 19whenever. It’s a generalization, of course; all musicians should know these things. And of course, there’s a chance that Artie was saying that so that I’d go home and study the repertoire more. But when I think of drummers like Morgan Childs, or the guy who sits behind that giant bass drum at Grossman’s on Saturday evenings, it fits perfectly.

Artie Roth once said to me – and I’m paraphrasing – that the drummer is the encyclopedia of the ensemble, the player who knows the repertoire most intimately, who can most immediately call up what happened on this chorus of that recording in Febtober of 19whenever. It’s a generalization, of course; all musicians should know these things. And of course, there’s a chance that Artie was saying that so that I’d go home and study the repertoire more. But when I think of drummers like Morgan Childs, or the guy who sits behind that giant bass drum at Grossman’s on Saturday evenings, it fits perfectly. Harrison Vetro, the only other drummer-as-leader I’m aware of in the clubs this month, was a classmate of mine at York University. Walking around the halls in York’s music building, you can always hear people practising, because those doors, thick though they may be, are not soundproof by any stretch of the imagination. Drummers who used the rooms at York could be divided into two categories: those who play, and those who practise. Sometimes, you could walk by and hear someone blazing around the drums with (or, you know, without) remarkable speed and accuracy. That was a player. Someone who was in there to keep playing what they already do well. Or just to blow off steam.

Harrison Vetro, the only other drummer-as-leader I’m aware of in the clubs this month, was a classmate of mine at York University. Walking around the halls in York’s music building, you can always hear people practising, because those doors, thick though they may be, are not soundproof by any stretch of the imagination. Drummers who used the rooms at York could be divided into two categories: those who play, and those who practise. Sometimes, you could walk by and hear someone blazing around the drums with (or, you know, without) remarkable speed and accuracy. That was a player. Someone who was in there to keep playing what they already do well. Or just to blow off steam.