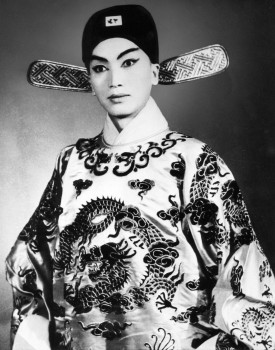

The Reshaping of Ryga’s Rita Joe

In this exciting month Toronto will see the world premieres of two new Canadian operas. The first, The Overcoat by James Rolfe, opens March 29 and is covered elsewhere in this issue. The other is The Ecstasy of Rita Joe by Victor Davies, which will be presented March 24 and 25 by VOICEBOX: Opera in Concert. Having interviewed Davies last month and pored through his background paper for the work, the opera looks to be one of his most important compositions.

The play has had many subsequent productions, most recently at the National Arts Centre in 2013 with an all-Indigenous cast. In 1971 the Royal Winnipeg Ballet produced a ballet based on it choreographed by Norbert Vesak to music by Ann Mortifee, revived most recently in 2011.

In answer to the question of how Davies came to create an opera based on the play, he writes in his background paper: “The genesis of the idea, that I should make an opera of the play, came from the insistence/encouragement of two dear friends: well-known Indigenous stage and screen actor August Schellenberg, the original Jaimie Paul in the premiere production of the play in 1967, and director/producer John Juliani who produced the CBC radio adaptation of the play for which I composed the music. Both were convinced the play contained an opera.

“Ultimately, my two friends were right. The play is wonderful material for an opera. It is richly textured and contains vibrant larger-than-life characters, a classic tragic love story, the theme of young ideas and ambitions thwarted, the clash between value systems, both societal and generational, pathos, moments of wonderful humour, the underlying inner drive which calls for music to emerge in song, and richly poetic dramatic prose to inspire heightened lyric melody.”

Nevertheless, Davies was still concerned whether today a self-described “old white guy” should write an opera about Indigenous people. To determine if he should undertake the project, he consulted Rebecca Chartrand, a singer and friend with whom Davies collaborated for the Indigenous music in the Opening Ceremonies of the 1999 Pan Am Games in Winnipeg and who is the Aboriginal Consultant for Seven Oaks School Division in Winnipeg.

As Davies explains, “Her immediate reaction was that I must write the opera. She said it spoke directly to the current and important discussion about the missing and murdered Indigenous women. This was a turning point for us both. Since this initial meeting until the present she has been a constant force in urging us to bring the opera to life.”

In addition to Chartrand, Davies consulted and was encouraged in the creation of the opera by such members of the Indigenous community as playwrights Thomson Highway and Kevin Loring, and the chiefs of various First Nations including Chief Len George (son of Chief Dan George, who appeared in the play’s premiere).

In answer to the question why the play should become an opera, Davies lists four goals: “to bring the story, characters and their issues to new life powered by music; to put the story into a new frame to engage new publics; to create an important and viable vehicle for Indigenous opera singers; and to be a catalyst in the discussion about issues between Indigenous peoples and Canadian society at large.”

A further question Davies addresses is why a play from 1967 should become an opera now. “This opera speaks to the important topic of the missing and murdered Indigenous women. Fifty years since the play’s creation, many serious issues are still unresolved in Indigenous life: tensions between the reserve and the city and the values they represent regarding stewardship of nature vs. modernity, conflicts between generations, the Indigenous world vs. the legal system, and prejudice against Indigenous people in general, all issues which underpin the problem of the missing and murdered women, and the residential school system.”

Davies says that Chartrand and Chief Isadore Day in Toronto and Chief Nepinak in Winnipeg “all spoke about how important they felt the opera would be in bringing Indigenous issues to mainline audiences in a new, more powerful way. They felt that bringing their story to the stage for audiences to whom the Indigenous story was nothing but a TV clip or a newspaper footnote would have an enormous impact. With characters with whom the audience could identify, who were alive, had aspirations, humour, and though their lives have a tragic end, the portrayal of these lives powered by music would bring home their story.”

Davies approached Opera in Concert three years ago about producing the work, and OiC organized a two-day workshop focusing on the libretto, which he also wrote. In transforming the play to an opera Davies made many changes. One was to eliminate the character of the Singer, a figure present in the play primarily to satirize the lack of understanding of liberal white people about what is happening to Indigenous people. While the action shifts back and forth in time, Davies’s libretto tells the story in chronological order. The five times Rita Joe is called before a magistrate become part of the libretto’s organizing structure.

In commenting on the score, Davies says: “This work will be unlike anything I have done, rooted in the ethos of the contemporary worlds of the reserve, the streets and the city. There will be no actual Indigenous music or language, but I will create music which reflects Indigenous music, the characters themselves and their place in both reserve and city with the necessary contemporary grit, energy and texture of the 60s. However melody, rhythm, accessibility and immediacy are hallmarks of my music and will be in this work too. The score will be eclectic in style as befits characters and action.” Davies says that the music will range from the tonal and melodic for arias for Rita Joe and Jaimie Paul to the atonal and dissonant for scenes of violence and conflict. The music is not organized through leitmotifs in the Wagnerian sense, but it is shaped through the use of recurring themes associated with certain characters and actions.

For the VOICEBOX: Opera in Concert production, all the principal roles will be sung by Indigenous Canadian artists. Mezzo Marion Newman will sing the title role. Baritone Evan Korbut, a recent Stuart Hamilton Memorial Award winner, will sing the role of Jaimie Paul. Mezzo Michelle Lafferty will be Sister Eileen, baritone Everett Levi Morrison will be Father David Joe and mezzo Rose-Ellen Nichols will be the Old Woman. The Opera in Concert Chorus will take on a wide array of roles: members of the court, street women, women on the reserve and in jail and more.

For the VOICEBOX: Opera in Concert production, all the principal roles will be sung by Indigenous Canadian artists. Mezzo Marion Newman will sing the title role. Baritone Evan Korbut, a recent Stuart Hamilton Memorial Award winner, will sing the role of Jaimie Paul. Mezzo Michelle Lafferty will be Sister Eileen, baritone Everett Levi Morrison will be Father David Joe and mezzo Rose-Ellen Nichols will be the Old Woman. The Opera in Concert Chorus will take on a wide array of roles: members of the court, street women, women on the reserve and in jail and more.

For the OiC production Guillermo Silva-Marin will serve as dramatic advisor. Robert Cooper will conduct the cast, the OiC Chorus and an ensemble of piano, cello, violin, clarinet and saxophone. The latter four instruments Davies says will add more “colour and weight” to the music than would piano alone. (While his last opera for Manitoba Opera, Transit of Venus (2007), employed an orchestra of 68, Davies says that for a full production of Rita Joe, he would be happy with an ensemble of 16.)

Attending the OiC performances will be representatives of Manitoba Opera and Vancouver Opera who may determine whether Davies’ opera moves on to future productions with their companies. For now, Davies is filled with gratitude. He writes that he gives “many thanks to dear friends both past and present who have given me... the passion and joy to search for the truth in the beautiful poetry of George Ryga. My hope is that those who see it as it emerges, will feel the same.”

Revised, 20/03/18: The third-to-last paragraph of this story has been revised to remove the statement that mezzo Marion Newman, who sings the title role of Rita Joe, also served as an advisor on the project. While she met twice, informally, with the composer during the development of the project, the nature of the input offered and the extent to which it was accepted were not sufficient to warrant describing the role as advisory. Permission was neither sought by the composer nor given by Ms. Newman to characterize her role as that of advisor.

Christopher Hoile is a Toronto-based writer on opera and theatre. He can be contacted at opera@thewholenote.com.