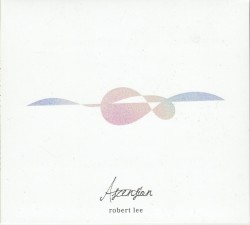

Ascension - Robert Lee

Ascension

Ascension

Robert Lee

Independent (robertleebass.com)

Up-and-coming Toronto acoustic bassist, composer and bandleader Robert Lee, has released this delightful debut album, an energizing and unique foray into the contemporary jazz world. The record maintains an interesting balance showcasing Lee’s talent as a composer and bassist while putting the spotlight on the other fantastic musicians featured throughout, such as JUNO Award-winning saxophonist Allison Au, well-known guitarist Trevor Giancola and vibraphonist Michael Davidson. The album takes inspiration from songwriters such as Bon Iver, Christian McBride, Brian Blade and Iron & Wine, making for a unique musical blend of “modern chamber music, jazz and contemporary folk.”

Whether the listener likes traditional or more modern jazz, each piece brings forth elements of both, making this a downright treat for the ear. The title track starts off the album and is a deeply personal and introspective story about “searching for the greater meaning in life” which is reflected in the wandering, yet positivity inducing saxophone melody and a general sense of discovery felt throughout the piece. Burton’s Bounce is a great, swing-style piece with nimble movement in Lee’s pizzicato bass line and the dancing saxophone, vibraphone and guitar solos. Closing out the album is Cardinal on the Cobblestone, a beautiful track in which Mingjia Chen’s captivating voice, Ginacola’s soft guitar riffs and Lee’s gracefully plucked notes meld together for an uplifting and wonderful end to this musical journey.