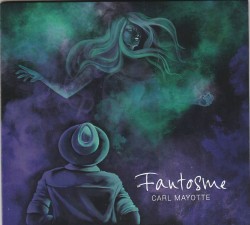

Fantosme - Carl Mayotte

Fantosme

Fantosme

Carl Mayotte

Independent (carlmayotte.com)

Montreal bassist Carl Mayotte has just released his debut CD, which was co-conceived by Mayotte and the iconic Michel Cusson (UZEB). This evocative project features ten original compositions (mainly penned by Mayotte), which embrace the indelible burst of artistry and creativity from influential 1970s artists such as Weather Report, Frank Zappa, Hermeto Pascoal, Chick Corea and Pat Metheny.

Mayotte, who performs masterfully here on electric and fretless bass, has also assembled a hungry pack of young jazz lions, who perform this challenging material with boundless energy as well as technical thrills and chills. The cast includes Gabriel Cyr on electric guitar; Francis Grégoire on keyboards and synthesizers; Stéphane Chamberland on drums; Damien-Jade Cyr on tenor, alto and soprano; Jean-Pierre Zanella on alto and flute; Patrice Luneau on baritone; Remi Cormier on trumpet; Emmanuel Richard-Bordon on trombone; Luke Boivin on percussion and Raymond Gagnier on voice.

First up is the two-part suite, Le Fantosme. Part 1, Le Poltergeist, is spooky and otherworldly, with synth-infused structures and a theatrical use of voice and breathing. Part 2, Le Polisson segues into a face-melting drum solo from Chamberland, followed by a funky big band explosion, replete with a fine bass solo and a caustic, Jan Hammer-ish synth solo. Sumptuous flute work by Zanella kicks off the fast-paced O Commodoro, and the spirit of Jaco Pastorious can be felt by Mayotte’s bass work throughout this invigorating composition. Cormier’s volcanic trumpet adds incredibly, while the band morphs into a second-line influenced passage, and then back to the lilting head… sheer beauty. A stand-out is Marise – an ego-less portrait of Mayotte’s incredible skill and melodic sensibility.