jazz, eh? - March 2014

Many musicians act as their own agents, produce and distribute their own recordings and promote their own concerts, but a few take on far greater roles, developing performance spaces and record labels, helping create vital scenes. Three such figures are Vancouver’s Cory Weeds, Toronto’s Ken Aldcroft and Rimouski’s Éric Normand.

Tenor Saxophonist Cory Weeds is an all-purpose advocate for mainstream modern jazz, running Cory Weeds’ Cellar Jazz Club and the very active Cellar Live label. Canada/U.S. musical exchanges figure in three recent releases. Let’s Go! (CL 013013 cellarlive.com) documents Weeds’ visit to New York’s Smoke Jazz Club with his regular associates, pianist Tilden Webb, bassist Ken Lister and drummer Jesse Cahill, and adds New York trombonist Steve Davis. Recorded at the end of a 19-performance tour, the experience shows. The music is a pure distillation of hard-bop, featuring tight-knit, spirited playing throughout, highlighted by the muscular lyricism of the tenor/trombone combination. A highlight is a reflective rendering of the late trombonist/pianist Ross Taggart’s ballad Thinking of You.

Tenor Saxophonist Cory Weeds is an all-purpose advocate for mainstream modern jazz, running Cory Weeds’ Cellar Jazz Club and the very active Cellar Live label. Canada/U.S. musical exchanges figure in three recent releases. Let’s Go! (CL 013013 cellarlive.com) documents Weeds’ visit to New York’s Smoke Jazz Club with his regular associates, pianist Tilden Webb, bassist Ken Lister and drummer Jesse Cahill, and adds New York trombonist Steve Davis. Recorded at the end of a 19-performance tour, the experience shows. The music is a pure distillation of hard-bop, featuring tight-knit, spirited playing throughout, highlighted by the muscular lyricism of the tenor/trombone combination. A highlight is a reflective rendering of the late trombonist/pianist Ross Taggart’s ballad Thinking of You.

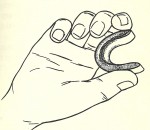

The recording venue switches to Weeds’ own club for American guitarist Peter Bernstein with the Tilden Webb Trio (CL 042613). Along with bassist Jodi Proznick, Webb and Cahill are once again models of support: Webb a worthy foil to Bernstein, turning out long lines that coil and twist, alive with melodic surprise, and Cahill providing animating drive and prodding rhythmic detail. With a distinctive singing tone, rare sustain and inspired virtuosity, Bernstein finds new dimensions in standards and jazz classics, from a heart-felt Darn that Dream to elegiac renderings of John Coltrane’s Wise One and John Lewis’ Django.

The recording venue switches to Weeds’ own club for American guitarist Peter Bernstein with the Tilden Webb Trio (CL 042613). Along with bassist Jodi Proznick, Webb and Cahill are once again models of support: Webb a worthy foil to Bernstein, turning out long lines that coil and twist, alive with melodic surprise, and Cahill providing animating drive and prodding rhythmic detail. With a distinctive singing tone, rare sustain and inspired virtuosity, Bernstein finds new dimensions in standards and jazz classics, from a heart-felt Darn that Dream to elegiac renderings of John Coltrane’s Wise One and John Lewis’ Django.

The cross-border emphasis continues with tenor saxophonist Pete Mills’ Sweet Shadow (CL 070813). Originally from Toronto (his CD includes a photo of Charlie Parker’s autograph, collected at the 1953 Massey Hall concert by his father, Ernie), Mills, who teaches at Denison University in Ohio, is a wildly inventive player with a light, airy sound and solid fundamentals. Sam Rivers and Joe Henderson likely number among his inspirations, while his themes include Roland Kirk’s Serenade to a Cuckoo and Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend. Aided by a first-rate New York band that includes guitarist Pete McCann and drummer Matt Wilson, Mills also plays two freely improvised duets with Wilson.

The cross-border emphasis continues with tenor saxophonist Pete Mills’ Sweet Shadow (CL 070813). Originally from Toronto (his CD includes a photo of Charlie Parker’s autograph, collected at the 1953 Massey Hall concert by his father, Ernie), Mills, who teaches at Denison University in Ohio, is a wildly inventive player with a light, airy sound and solid fundamentals. Sam Rivers and Joe Henderson likely number among his inspirations, while his themes include Roland Kirk’s Serenade to a Cuckoo and Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend. Aided by a first-rate New York band that includes guitarist Pete McCann and drummer Matt Wilson, Mills also plays two freely improvised duets with Wilson.

Since migrating from Vancouver more than a decade ago, guitarist Ken Aldcroft has become an essential figure in the Toronto improvised music scene, producing performance series and acting as one of the founders of AIMToronto, an association of improvisers. Documenting his own work on his Trio Records since 1997, Aldcroft has just released two contrasting sessions.

Aldcroft’s Convergence Ensemble is his principal group, a long-standing quintet that has been a laboratory for his developing compositional approach. Saskatoon (TRP-017 kenaldcroft.com/triorecords.asp) was recorded at the Bassment in 2007, so it’s clearly an old performance with enduring significance. Alto saxophonist Evan Shaw, trombonist Scott Thomson, bassist Wes Neal and drummer Joe Sorbara share Aldcroft’s commitment to the group, and it’s apparent in every instant of this music, a consistent collective creation on Aldcroft’s themes. Our Hospitality cleverly integrates free jazz, swing and instrumental click languages.

Aldcroft’s Convergence Ensemble is his principal group, a long-standing quintet that has been a laboratory for his developing compositional approach. Saskatoon (TRP-017 kenaldcroft.com/triorecords.asp) was recorded at the Bassment in 2007, so it’s clearly an old performance with enduring significance. Alto saxophonist Evan Shaw, trombonist Scott Thomson, bassist Wes Neal and drummer Joe Sorbara share Aldcroft’s commitment to the group, and it’s apparent in every instant of this music, a consistent collective creation on Aldcroft’s themes. Our Hospitality cleverly integrates free jazz, swing and instrumental click languages.

For sheer playfulness, there’s Aldcroft’s duo with drummer Dave Clark, Hat and Beard: The Music of Thelonious Monk. Their second all-Monk program, Reflections (TRP-018), extends Monk’s own assertive rhythms, clashing phrases and unlikely chord changes. The approach, with Clark’s explosive, weirdly precise cacophony and Aldcroft’s acid-toned minimalism, may owe as much to the members of Captain Beefheart’s Magic Band as to Monk himself. It’s all a delight, but Pannonica and Monk’s Dream are stand-outs.

For sheer playfulness, there’s Aldcroft’s duo with drummer Dave Clark, Hat and Beard: The Music of Thelonious Monk. Their second all-Monk program, Reflections (TRP-018), extends Monk’s own assertive rhythms, clashing phrases and unlikely chord changes. The approach, with Clark’s explosive, weirdly precise cacophony and Aldcroft’s acid-toned minimalism, may owe as much to the members of Captain Beefheart’s Magic Band as to Monk himself. It’s all a delight, but Pannonica and Monk’s Dream are stand-outs.

While Weeds and Aldcroft work in major population centres, bassist Éric Normand, through sheer creativity, commitment and energy, has somehow made Rimouski, Quebec a hotbed for free improvisation, producing concerts, drawing in international guests and releasing music in a welter of media on his Tour de Bras label.

While Weeds and Aldcroft work in major population centres, bassist Éric Normand, through sheer creativity, commitment and energy, has somehow made Rimouski, Quebec a hotbed for free improvisation, producing concerts, drawing in international guests and releasing music in a welter of media on his Tour de Bras label.

The acronym GGRIL may identify the large ensemble Grand Groupe Régional d’Improvisation Libérée, but it also suggests “guerrilla,” emblematic of Normand’s adaptive and spontaneous rebellion. GGRIL has released one of the year’s most beautiful records, Combines a red-vinyl LP in a clear plastic sleeve, (TDB 990001LP tourdebras.com). There’s a delightful sense of community get-together in the music, whether it’s using chance methodologies or two conductors simultaneously leading a collective improvisation, and it extends to the unlikely combination of instrumentalists: multiple percussionists, bassists, and guitarists with an accordionist among the featured voices.

At the opposite pole of media, there’s the insubstantial Rrrrrrrrrroyal Canadian Free Form Folk Experience (tourdebras.com) by the trio ofNormand, Halifax-based guitarist Arthur Bull, and Toronto percussionist Bob Vespaziani, also known as the Surruralisms. Available as a paid download or free streaming audio, the work consists of a single half-hour improvisation called Batoche’s Battle, a brilliant realization of Normand’s aesthetic, melding folk materials and instruments with the most radically concentrated, minimalist, electroacoustic improvisation. It’s an invitation to sample one of Canada’s most creative musical visions.

At the opposite pole of media, there’s the insubstantial Rrrrrrrrrroyal Canadian Free Form Folk Experience (tourdebras.com) by the trio ofNormand, Halifax-based guitarist Arthur Bull, and Toronto percussionist Bob Vespaziani, also known as the Surruralisms. Available as a paid download or free streaming audio, the work consists of a single half-hour improvisation called Batoche’s Battle, a brilliant realization of Normand’s aesthetic, melding folk materials and instruments with the most radically concentrated, minimalist, electroacoustic improvisation. It’s an invitation to sample one of Canada’s most creative musical visions.

Normand has also released the latest music by the Montreal-based trio Pink Saliva, with trumpeter Ellwood Epps, bassist Alexandre St-Onge and drummer Michel F. Côté also exploring electronics. Available as a download or a micro-edition CD, Il parait que... (TDBW0003) is a tangled forest of vital distorted sound, Epps’ amplified trumpet sounding like a raw nervein the undergrowth.

Normand has also released the latest music by the Montreal-based trio Pink Saliva, with trumpeter Ellwood Epps, bassist Alexandre St-Onge and drummer Michel F. Côté also exploring electronics. Available as a download or a micro-edition CD, Il parait que... (TDBW0003) is a tangled forest of vital distorted sound, Epps’ amplified trumpet sounding like a raw nervein the undergrowth.