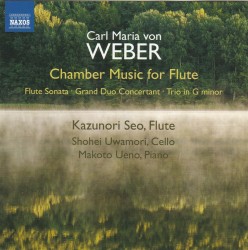

Carl Maria von Weber: Chamber Music for Flute - Kazunori Seo; Shohei Uwamori; Makoto Ueno

Carl Maria von Weber – Chamber Music for Flute

Carl Maria von Weber – Chamber Music for Flute

Kazunori Seo; Shohei Uwamori; Makoto Ueno

Naxos 8.573766 (naxos.com)

Carl Maria von Weber, best known for his operas, Der Freischütz and Oberon, also composed chamber music, some of which is to be found on this disc. I will pay the performers, fronted by flutist Kazunori Seo, the ultimate compliment: that I felt listening to this recording that I could hear Weber’s voice throughout. Yes, you can at times hear the influence of Beethoven and of his contemporary, Friedrich Kuhlau; but the music presented here is not mere imitation but an original take on, and within the stylistic parameters of, the time.

There is much to admire in the A-flat Major Sonata, the first work on this recording: the elegant phrasing in the opening movement, the dramatic dynamics and judicious use of vibrato in the slow second movement. In the second work, the Grand Duo Concertant, in which I hear the influence of Kuhlau, there is boundless but carefully managed excitement, drama and virtuosic flute playing matched at every moment by the effortless fluidity of pianist, Makoto Ueno.

To me, however, the high point in the disc is the third and last composition, the Trio in G Minor, in which flutist and pianist are joined by cellist Shohei Uwamori. Weber’s artistry reveals itself like an early morning sunrise: the first movement begins with the melancholic opening theme played first on the flute and then on the piano, which adds a new and unexpected layer of understanding of the music. But when the cello follows with a second theme, the effect is breathtaking!