It was my incredible fortune to be introduced to Howard Cable through a member of the Wychwood Clarinet Choir (that I conduct), who had been at a gathering with Howard and had asked him, as a lark, if he had ever written anything for clarinet choir.

It was my incredible fortune to be introduced to Howard Cable through a member of the Wychwood Clarinet Choir (that I conduct), who had been at a gathering with Howard and had asked him, as a lark, if he had ever written anything for clarinet choir.

Sure enough, he had, and for none other than the particularly talented clarinet section of the 184-piece North American Aerospace Defense Command (“NORAD”) Band, based in Colorado Springs. Howard guest-conducted, composed and arranged for the NORAD Band from 1960 to 1966. He wrote several selections for their clarinetists, most of which were never published. Luckily for us, two were. One, an arrangement of Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered from Pal Joey (Rodgers & Hart), Howard hadn’t heard played since 1962, and the other, Wind Song, an original composition, he had in fact never heard performed (though we’re not exactly sure why).

Howard quickly located the two published pieces and passed the music along to us. We invited him to conduct both pieces at our next concert and, to our delight, he accepted. I took the group through the songs for most of the rehearsal process and we arranged for Howard to be there the week of the show to take the reins.

There for the night! The night arrived. An intricate plan was in place for Howard to start out the rehearsal and to be driven home as soon as his pieces were done so that he didn’t have to sit there for two and a half hours on a hard church pew. I introduced myself and shook Howard’s hand. Of course, I had revered this legendary Canadian for years, but had not yet had the chance to meet him. I was a little nervous (slight understatement). Here I was, a strange new face, with 17 clarinetists in tow, about to play Howard Cable’s music for none other than the man himself. Even now, that night seems surreal. I took the group through our usual warm-up and invited Howard to the podium. Howard was on form (which I would later learn was how he always was). In no time, he had the notes weaving and whirling about with the group watching his every move, even from the low chair he sat in to conduct. He rehearsed for a while, but not too long, and then went back to the pew. “We’re ready to take you home now, Howard,” I said. “Oh no,” he replied. “I’m here for the night!”

After the colour returned to my face, I managed to muster up a faint smile and scurry off to put my own clarinet together. Next up on the rehearsal list was my solo feature for that concert, Clarinet on the Town, by Ralph Hermann, which would be led by our associate conductor, stellar arranger (and my former high school teacher) Roy Greaves. Luckily for me, I didn’t know about Howard’s new plan until that moment, so I didn’t really have time to get (any more) nervous. That particular solo had a lot of notes. “Well, here goes nothing,” I thought to myself.

After that, came another test. It was my turn to conduct, and I’d be up there for the remainder of rehearsal. It was hard to concentrate at times, when I could hear Howard’s cane tapping the beat behind me. Was the group not together, or was he just grooving along?

At the end of rehearsal, I told Howard (once again) that we were ready to take him home. Thinking he would most certainly decline, I also told him that a bunch of us would be immediately proceeding to our local post-rehearsal watering hole, and that he was welcome to join us. To our shock, he enthusiastically accepted. He came with us, drank (a lot of) black coffee and regaled us with all kinds of stories, from his time as the artistic director of the Royal York’s Imperial Room, to his summers in Charlottetown and his days at the CBC.

Choir musicians gradually started fading out, but not Howard. He and the few of us who remained were (politely) asked to leave by the server as chairs were going up on tables for closing time. That night was the only time we’ve ever shut down the bar after rehearsal. Usually it’s a half pint all-round with one side order of fries (we’re wild kids). We’re in and out in an hour. That night, I later discovered, was not an isolated incident of Howard closing down a bar. That night was also my introduction to a wonderful human being and a true kindred spirit.

One-trick pony: He didn’t say too much about the rehearsal that evening, and I was worried the entire time that he thought we were just a silly bunch of clarinet geeks. The next morning (a bit early, I might add, after our late night partying) the phone rang. It was Howard, calling with praises for the work I had done with the group the night before and also about my playing. “That piece is a one-trick pony,” he said. “You need another trick!” The following week at our Christie Gardens retirement home pre-show show, he arrived with a manila envelope. In six days, he had whipped up a brand new piece, dedicated to the Wychwood Clarinet Choir, with a solo part for me. We were all floored – and honoured. Figuring this was my “other trick,” we immediately programmed the piece for our next concert, but the music kept coming. A second number, which at first we assumed was a separate piece, was in fact a movement to follow the first one he had given us. We were overjoyed. We didn’t realize at the time that we were going to end up with a three-movement work titled the Wychwood Suite for solo clarinet and clarinet choir.

The following season, even more music came. Howard wrote for and conducted at several subsequent concerts, one of the highlights being a show featuring Howard’s young discovery, crooner Michael Vanhevel. The concert was a huge success, and included the likes of Terry Clark and Kieran Overs as our rhythm section.

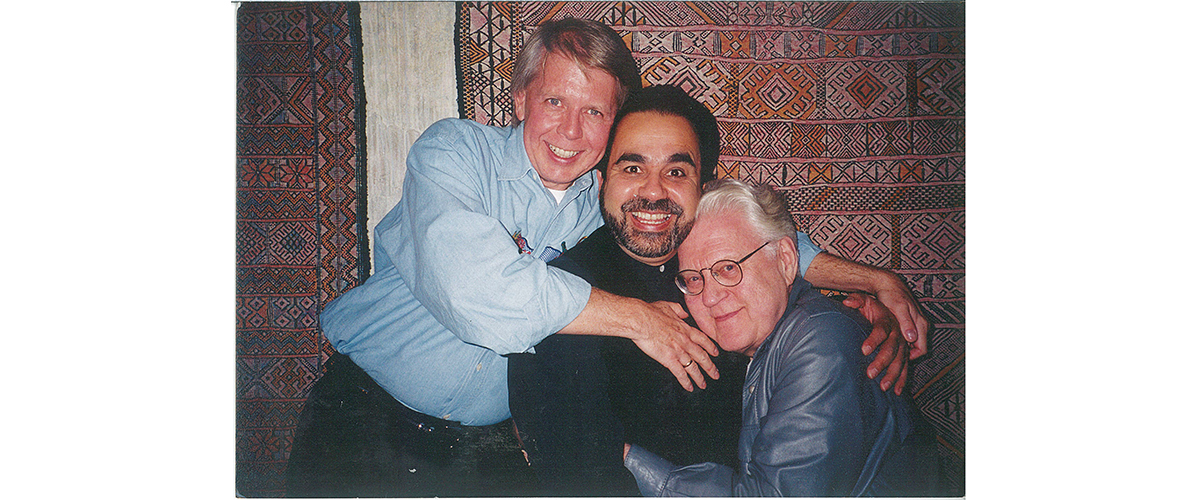

Since then, the WCC has been so fortunate to befriend not only Howard, but also Howard’s wonderful friends and family. Virtuoso trumpeter, conductor and arranger Bobby Herriot, and Fen Watkin, fantastic pianist and arranger, were colleagues and dear friends of Howard’s for decades. Due I’m sure to Howard’s initial convincing, the two have come to several of our concerts and have since been writing for our group. Bobby and Fen are now a special part of our WCC family. In fact, huge thanks to Bobby for helping with setting some facts straight for the historical accuracy of this article, and for regaling me with lots of funny, fascinating stories (some not suitable for print) of the antics, poignant moments and memories that Howard and Bobby shared.

On the road: Howard also helped behind the scenes to plan and imagine, with ideas for themed shows and other exciting projects both for the choir and for myself. He proudly became the WCC’s composer and conductor laureate, but mostly, he was our friend.

He would phone me after concerts to debrief. “It’s the maestro calling,” he would say. He would get frustrated if I didn’t answer right away and would call back incessantly until I did. One day, he told me how impressed he was with the work I was doing for the group and how far we had come in even the short time he had been with us. He explained that travelling and conducting were getting a bit more challenging for him, and that he wanted me to tag along … to learn from him, to get some orchestral conducting experience, and also to be there “in case”. “Sure!” I said (after pretending to think about it for a second or two), and thus began my new adventure as Howard’s associate conductor. He insisted on the word “associate” as opposed to the word “assistant,” with a long explanation having to do with the association (pardon the pun) it conjured up. He was a bit of a semantics guy and, when I knew him at least, quite firmly opinionated. He also saw through egos and was one of the most unpretentious people I have ever met. He couldn’t stand narcissists. I loved this about him, as we shared these strong sentiments. I asked him once why he didn’t use his “Doctor” title. “Too snobby,” he said, without missing a beat.

In February of 2015, 94-year-old Howard and I flew to Halifax to conduct his “Music of the Oscars” show with Symphony Nova Scotia. After a lovely visit on the plane where we discussed music, of course, and many other fascinating topics, we checked into the hotel. Later, we met up for dinner. Howard had his preferred Lord Nelson specialty, chicken pot pie. As we chatted over coffee and dessert (banoffee cake, another of Howard’s favourites), Jim Eager, the symphony’s music librarian and trombonist, dropped by to bring Howard his scores for the show. Since they were all his own arrangements, he apparently didn’t need them too far in advance!

Made of horseshoes: After our meal, I took Howard back to his room and went to unpack my suitcase. He asked me to check in on him before he went to sleep, so at about 11pm I knocked on his door, as requested. “Come in,” was the very faint reply. To my utter horror, I opened the door to find Howard lying crumpled on the floor. He had fallen on his way out of the bathroom and had been there for over two hours, unable to get up, let alone get to a phone. I tried to lift him off the floor on my own, but no luck, so I called the front desk for help. After we propped him up in a chair, I asked him what was hurting, and thankfully in many ways, he said he thought that only his left hand had been affected. (I later told him he was made entirely of horseshoes!) The hand was pretty swollen, though, so we got him some ice. I asked if he wanted to go to the hospital and he quickly replied, very definitively, “Not a chance!” He sat for a few minutes in silence, visibly thinking things through. (It felt like forever!) Then, looking at me with an intense stare (and somehow a twinkle in his eye at the same time), he proclaimed, “I think you’d better conduct the whole show.”

For previous concerts, I had been given a full set of scores in advance, “just in case,” but for this particular occasion, the scores were in Halifax, so I only had the three numbers I was originally scheduled to conduct. After I picked my jaw up off the floor, he quickly sent me away with the rest of the pile (there were nine other pieces) and I stayed up all night trying to absorb as much as humanly possible before the 10am rehearsal downbeat. (I also silently checked on him again at 3:30am to make sure he was okay, and he was happily snoring in his chair). To add to the score crash-course fun, many of the numbers were piano reductions so I didn’t have a lot to go on, and some were hand-written in Howard’s infamous chicken scratch – even with empty bars! Only Howard knew what filled them, and I had to find out as we went along. In case you aren’t familiar with Howard’s writing style, he is the king of key changes and a huge fan of long (and expertly crafted, I might add) medleys, with ones for this particular show often containing six and seven tunes each. And for every tune, a transition, which are tricky moments for conductors to navigate even when there is actually time to prepare.

The next morning, at the insistence of the orchestra’s administrative staff, Howard was taken to the hospital, his hand X-rayed (he had broken some bones) and put into a cast. When I came back to the hotel after the two-service day, he slowly looked up from his newspaper, put down his coffee cup, asked what took me so long (as if he had casually been lounging around all day) and eagerly awaited my report. I filled him in and he told me how proud of me he was for agreeing to take on this challenge. He added that he had already heard positive reports about the day from several people. I was relieved … and exhausted.

Unstoppable! By the end of the dress rehearsal the next day, things were sounding pretty decent. It was a blessing, of course, that the musicians of Symphony Nova Scotia are absolutely incredible. Howard ended up emceeing the show from his wheelchair beside me, which meant that the audience was still able to hear his wonderful tales and anecdotes – a huge part of why many have flocked to Howard’s shows over the years. And good news for me, I got two cracks at it, with a second show two days later – so after the complete out-of-body experience of the first one, I was able to be a lot more relaxed and present the second time around. Luckily, both shows ended up going off without a hitch, and the memory of turning around to bow after the Over the Rainbow encore, seeing Howard with tears streaming down his face, is one that will be deeply etched in my mind for the rest of my days. Of course, I lost it too, at that point, and we hugged each other for a long time as we bowed. I have never had a more stressful or a more exhilarating musical experience. What a ride.

And what a thrilling trip it was to be able to know Howard in his last years. He had a youthful spirit and a sparkle in his eye that kept him young at heart until the day he died (I was so fortunate to be able to have dinner with him two days before he passed away). Howard Cable touched a lot of souls. His cheeky and contagious smile was usually enough to win you over, and when music was thrown into the equation, Howard Cable was absolutely unstoppable.

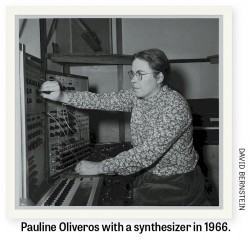

November 24 2017 will mark one year since the passing of Pauline Oliveros, a beautiful soul who brought to the world the practice of what she called Deep Listening.

November 24 2017 will mark one year since the passing of Pauline Oliveros, a beautiful soul who brought to the world the practice of what she called Deep Listening. I then asked Tina to relate these earlier experiences to her recent experiences in Toronto this past summer facilitating Deep Listening Workshops:

I then asked Tina to relate these earlier experiences to her recent experiences in Toronto this past summer facilitating Deep Listening Workshops: