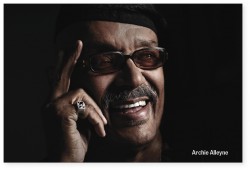

June of this year brought a rash of deaths which rocked the jazz community – locally, bassist Lenny Boyd and drummer Archie Alleyne – and internationally, jazz pioneer Ornette Coleman and third-stream-composer Gunther Schuller. I wrote memorial blogs about Coleman, Schuller and Boyd, who was my bass teacher. These can be read by accessing my site at wallacebass.com. I wasn’t going to write about Archie Alleyne’s yet: I just didn’t have another obituary piece about such a good friend in me. And then David Perlman – the editor of this publication – asked me to write about Archie in this issue of The WholeNote.

June of this year brought a rash of deaths which rocked the jazz community – locally, bassist Lenny Boyd and drummer Archie Alleyne – and internationally, jazz pioneer Ornette Coleman and third-stream-composer Gunther Schuller. I wrote memorial blogs about Coleman, Schuller and Boyd, who was my bass teacher. These can be read by accessing my site at wallacebass.com. I wasn’t going to write about Archie Alleyne’s yet: I just didn’t have another obituary piece about such a good friend in me. And then David Perlman – the editor of this publication – asked me to write about Archie in this issue of The WholeNote.

Oddly, it was while attending the early spring memorial celebration of Jim Galloway – who used to write in these very pages – that I first learned that Archie was seriously ill. I hadn’t seen Archie in some time and while looking about for him at Jim’s event I was told that he wasn’t expected to live through the summer, a body blow. He didn’t even make it that far, dying on June 8 of prostate cancer. Perhaps it’s just as well he went this quickly, as he was suffering, but the speed of it was still shocking. Archie was such a zestful man, so integral a part of Toronto’s musical scene in so many ways and for so long that it’s hard to believe he’s gone. The palpable gap of his absence from Galloway’s event was a strange kind of rehearsal for missing him, something we’ll all have to get used to.

Many readers will already know of Archie’s accomplishments both as a musician and a social activist promoting greater awareness of jazz, black culture and racial issues around these parts; he had tremendous energy and got a lot done. This is more of a personal look: Archie as I knew him and as I’d like to remember him.

I first came to know Archie around 1979, when he hadn’t yet begun his comeback as a drummer. He’d left music in 1967 after a near-fatal car accident left him in hospital for almost a year and slightly realigned his handsome face (though he was still a ladykiller). After recovering he went into business as a partner in The Underground Railroad, a soul food restaurant I enjoyed eating in and occasionally playing at. Even though he wasn’t playing in those days, I saw a lot of him at the various Toronto clubs I’d begun working at – George’s Spaghetti House, Bourbon St. and so on. He loved to go out to hear live music and hang out; he was a very gregarious, social guy. Always dressed sharply, laughing, telling stories in that rich Billy Eckstine voice, musicians generally gathered around; he was hard to miss. Being green and new to the scene, I wondered who this hip, dapper character with an elder’s presence might be. Eventually I was introduced to Archie, little knowing that this would be the beginning of a long and eventful friendship.

Not long after, he eased back into playing the drums, partly because the restaurant business was starting to flounder, but I suspect also because he missed music and had been itching to return. Either way, the restaurant world’s loss was the local jazz scene’s gain. It took him a short while to get back into playing shape, but if he’d lost anything during his long layoff, it didn’t show much. And besides, Archie was never a flashy technical player; he was mostly self-taught, a “feel” player, a swinger. All that he’d learned as the virtual house drummer at the Town Tavern from 1955 to 1966 came back to him pretty naturally. He and I started to play together here and there with some frequency. We formed a natural musical and rhythmic chemistry, mainly because he was easy to play with. He had a nice, relaxed ride-cymbal stroke and played good brushes. His playing could be summed up by something Lester Young suggested to him decades earlier: “Just a little tinkedy-boom for me, Arch, and we’ll go straight ahead, no fuss, no muss.”

In 1983, Archie hired me to play bass in the quartet he co-led with vibraphonist Frank Wright, with the redoubtable pianist Wray Downes aboard. Playing in this group was a large part of my musical education. Not only was I by far the youngest member – I was used to that – but in this case, I was also the only white member. There was never any friction, no overt or serious lecturing on racial issues from these veterans. However, their stories taught me that there were real racial barriers in Toronto of the kind I had previously (and naively) thought were restricted to the Jim Crow practices of the U.S.A. Archie had a sense of humour about this, as in the following story: He and I often backed up the great pianist Ray Bryant at the Montreal Bistro. Among my most prized photographs is one of me flanked by Ray and Archie. Just before Jim McBirnie pressed the button, Archie said “You’re the cream in the Oreo, Steve-o!” The resulting laughter is all over our faces in the photo.

I have very fond memories of playing in the Alleyne-Wright quartet and being accepted in it despite my young years. Because of Archie’s belief in classy presentation, we were surely the only group to play George’s in full tuxedos. I learned a great deal from Archie, not so much about the nuts and bolts of music, but more to do with comportment and the jazz history and traditions of Toronto, which he had absorbed so much of first-hand. He took joy not just in music-making, but in the personalities and stories of musicians, their eccentricities and individuality. He regaled me with tales about playing with such classic artists as Billie Holiday, Ben Webster and Lester Young: that they taught him not just about being professional, but about being a human being, about giving the music soul.

I well remember a special gig the quartet played for Ontario Lieutenant-Governor Lincoln Alexander at an event held to honour Prince Philip. It was very private, by invitation only, and both men got on famously. There was no press of any kind, which allowed the two public figures to relax. They enjoyed themselves immensely, playing darts, drinking pints and conversing freely with everyone; both really enjoyed the music. It was my first inkling of how Archie was equally at ease with ordinary people but also with those from the corridors of power and privilege, mostly because he treated everyone the same. I soon learned that virtually everybody knew and liked Archie, including some influential figures – Alexander, Roy McMurtry and many others. Archie used this connectedness to further the black Canadian musical community whenever and however he could. It was one of his greatest gifts.

For various reasons the Alleyne-Wright quartet petered out, but Archie and I continued working together, often forming the rhythm section for out-of-town artists. I remember the two of us backing trumpeter Tom Harrell, just when drummer Terry Clarke had returned to Toronto after years of living in New York. Hearing him for the first time, Clarke remarked that Archie’s splashing ride cymbal, taste and simplicity reminded him of Billy Higgins – high praise indeed.

Archie and I also did a very memorable tour of Ireland and Spain with Montreal-based pianist Oliver Jones in the fall of 1989, the beginning of which we barely survived. Archie and I flew together to Heathrow Airport, where we were to catch a connecting flight to Cork, home of the Guinness Jazz Festival. That very day the British Isles and the North Atlantic were ravaged by one of the worst storms to hit that area in the 20th century, with untold damage caused by ferocious high winds and lashing rain. Out of this chaos we eventually caught an Aer Lingus flight which attempted unsuccessfully to land at Cork and Shannon. I’ve never been as certain of my imminent death as during that flight. The plane was being tossed around like a soda cracker just above the roiling sea, which seemed sure to swallow us up whole. Finally the pilot managed a miraculous landing at Dublin Airport, to the most heartfelt and relieved ovation I’ve ever heard.

That was just the beginning of our adventures, however. We still had to get to Cork, and we had no idea where our instruments were. We found Oliver, and with the alto saxophonist Herb Geller in tow, they shared a rocky car ride to Cork with us. Fortunately we had a few days off to recover and eventually my bass and Archie’s drums showed up on the tarmac in Cork, but not his priceless K-Zildjian cymbals. They’d evidently been stolen and I felt terrible that such a huge and irreplaceable part of his sound had been taken so unjustly. Some local drummers lent Archie good cymbals for the rest of the tour and eventually he bought himself some new ones, never missing a beat. That was Archie all over, aware of the past but always looking ahead. I’ll long remember his ironic and good-humoured variation of the old Irish greeting – “Top of the mornin’, mothers!” Or something like that anyway.

In the years since, Archie and I played together less often and saw a little less of each other. Our relationship remained intact though; he was the type who kept his friends. He became more involved with his special projects, including the Evolution of Jazz Ensemble, which did a great deal to spread the awareness of jazz and Canadian black history in schools. He also formed Kollage, a band in which he gave many young musicians the opportunity to learn from his vast experience by playing under his direction. This passion for mentoring young musicians led to the establishment of the Archie Alleyne Scholarship Fund in 2003, to recognize and encourage excellent young black jazz students in Canada.

Archie Alleyne was an old-school musician who came up the hard way, self-taught and on the bandstand. He valued both classroom-oriented musical education as well as a more reality/experience-based approach – the AASF and Kollage allowed him to offer the best of both worlds. In late 2011, his vast contributions to this country’s society and culture were recognized with Canada’s highest civilian honour when he was named a Member of the Order of Canada. This was greeted with great satisfaction and pride by Archie and his many friends and colleagues.

I regret that I didn’t see more of Archie in the last few years or in the days and weeks before he passed. But I’m happy to have known him so well, very grateful to have shared so many musical experiences with him and to have learned so much from them. I know I speak for many Toronto musicians when I say that I’ll miss Archie a lot and also in saying a big thank you to him for leaving the city’s jazz scene a much better place for his presence in it.

Toronto bassist Steve Wallace writes a blog called “Steve Wallace – jazz, baseball, life and other ephemera” which can be accessed at wallacebass.com. Aside from the topics mentioned, he sometimes writes about movies and food.