Leon Fleisher (July 23, 1928 - August 2, 2020) – The Music is the Star

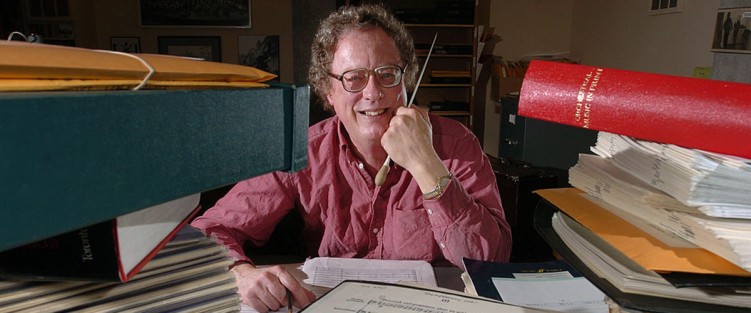

Leon Fleisher devoted his life to the piano, first as the foremost American pianist of his generation. The much-lauded collection of LPs he recorded in the 1950s and 60s was capped by a matchless collaboration with George Szell and the Cleveland Orchestra. Then, in 1965, he found it difficult to use the fingers of his right hand, a condition diagnosed as focal dystonia, restricting his repertoire to pieces written for the left hand. But his musical reach grew in other ways – conducting and teaching.

Leon Fleisher devoted his life to the piano, first as the foremost American pianist of his generation. The much-lauded collection of LPs he recorded in the 1950s and 60s was capped by a matchless collaboration with George Szell and the Cleveland Orchestra. Then, in 1965, he found it difficult to use the fingers of his right hand, a condition diagnosed as focal dystonia, restricting his repertoire to pieces written for the left hand. But his musical reach grew in other ways – conducting and teaching.

Based in Baltimore at the Peabody Institute from 1959 on, he also taught at the Curtis Institute in Philadelphia (1986-2011) and in Toronto, where he was one of the cornerstones of the Glenn Gould School, occupying the Ihnatowycz Chair in Piano. In his late 60s, Fleisher regained the use of his right hand with botox and rolfing treatments and resumed limited concertizing and recording (as detailed in the 2006 Oscar-nominated short film, Two Hands, available on YouTube).

One measure of the man can be gleaned by the memorable masterclasses he gave during his frequent visits to Toronto (of which I was fortunate to audit 27, between November 2014 and April 2019). They were inspirational and memorable, strewn with anecdotes and words of wisdom. All in the service of bringing the notes on the page, the composer’s intentions, to the fore. “In our celebrity-based culture we are not the stars. We are indispensable, [we’re] needed to bring the music to life,” he said. “[But] the music is the star.”

Fleisher always sat in the front row of Mazzoleni Hall, aisle seat on the left side, with the score on a music stand in front of him. When a student finished their presentation Fleisher stayed seated, silent for a long moment. He then asked the student if they had any concerns about what they had just played – anything that Fleisher might help with. I remember one student voicing concern about his nerves prompting Fleisher to illustrate a case of nerves by one of the greatest composer/pianists of the 20th century.

Fleisher was five years old at the time and had been taking piano lessons for six months. His mother took him to hear Rachmaninoff at the War Memorial Concert Hall in San Francisco. After the concert, his mother dragged him backstage to meet the great musician, who suffered from nervous tension whenever he was onstage. Fleisher’s memory was clear: “He was very tall, short haircut, face lined like the map of Russia.” In a heavy Russian accent, Rachmaninoff asked Fleisher, “You, pianist?” A pause. “Bad business …”

Fleisher’s conclusion: “There are bad nerves and good nerves. How much of what I want to do will I be able to communicate? That’s the good nerves.”

At one masterclass I attended, on November 29, 2014, Fleisher was into the second piece of the morning masterclass when Brahms’ Piano Quartet in C Minor Op.60 triggered a recollection: “I had the pleasure once – and it really was a pleasure – of playing this with three guys named Jascha [Heifetz], Grisha [Piatigorsky] and William [Primrose].” What did he remember? That there was no piano in the green room in the hall in San Francisco, which upset Fleisher, prompting Piatigorsky to calm his nerves: “Leonski, warming up before the concert is like doing breathing exercises before dying.”

The next day after listening to Rebanks Fellow Jean-Sélim Abdelmoula play Beethoven’s penultimate piano sonata, Op.110, Fleisher mused: “It suddenly occurred to me that Beethoven has innumerable ways of expressing his final journey into heaven. I’m getting to that point myself,” he said. “How does one face the end of this life and the beginning of the next?”

When Fleisher was nine, the legendary pianist Artur Schnabel invited him to be his pupil, first in Lake Como, Italy, then in New York. “For ten years I studied with one of the great teachers of the 20th century – for two years after, I was absolutely lost until I discovered that everything he taught me was lodged in my cerebellum and it was just a matter of uncovering it,” he said. “One of the ways to do this is by singing the notes and the rhythm (and deciding whether the consonant is soft or hard). Singing gives you a much clearer idea of what you’re facing.”

For 60 years Fleisher continued a musical legacy traceable directly back to Beethoven through Schnabel and Schnabel’s teacher Theodor Leschetizky who studied with Carl Czerny, Beethoven’s pupil.

Schnabel references were plentiful in Fleisher’s masterclasses, especially when discussing music by Beethoven and Schubert. Looking back over my records, I see that on April 21, 2017, a student playing Brahms’ Intermezzos Nos. 4-6, Op.116 triggered Fleisher’s analytical instincts before he settled into a surprising Schnabel anecdote. “We work in two dimensions simultaneously: sound – loud and soft and everything in between – and time, which can be strict or with a degree of flexibility. I think time is the more difficult dimension to work in because the pulse can easily become mechanical sounding. A curious thing – Brahms’ music flows at a specific personal rate – it flows more like lava than water. And there’s a richness and a warmth to it.”

And then the anecdote: “My teacher, Schnabel, let it drop very casually one day in a lesson, that he had known Brahms. Brahms had a habit in Vienna on Sunday of going into the Vienna woods with a basket for a picnic. The little Schnabel went along one day. Brahms asked, ‘Are you hungry?’ before [commencing eating]. And after he asked, ‘Have you had enough?’ – and that was his conversation with Brahms.”

At that point, Fleisher got up and moved to the piano, accompanying the student in the upper octaves of Brahms’ fourth intermezzo, but with his left hand. It was truly inspirational. And with his singing, he coached a much better performance. “Good. That was a good sound. And now the memory of something so fragile – when a phrase is repeating it’s not necessarily an echo but a chance to do it more beautifully. It’s a memory, very fragile. If you do too much it will disappear – be very still.”

Another tack he took with a student was to ask “To what extent were you successful in doing what you tried to do?” – an opening gambit designed to encourage scrutinizing the score and elevating the student’s performance. He never missed a chance to make one of his favourite points: “Music is a horizontal activity that goes through all sorts of adventures – everything has to be part of the entire arc – it is filled with vertical events like beats in a bar – the danger is that it is filled with coffin nails.”

Fleisher’s pedagogy was filled with aphorisms. “Playing beautifully is not necessarily beautiful music.” Or “A metronome is a machine; it has nothing to do with music.” And “Romantic means playing long notes short and short notes long.” He always deferred to the score: “You are the actor; the music is the director.” And paradoxically (discussing Schubert’s Sonata D958): “In time you can build the structure with slight rhythmic distortions. Great art in a sense always involves healthy distortion.”

Other comments reflected Fleisher’s playful mind: he once described Beethoven’s markings in the fourth movement of his Sonata No.13 “Quasi una fantasia” as not just accents – “Beethoven has a habit of poking his elbow into your ribs.”

And his analytical prowess: “Of music’s three elements, rhythm is the most important. Harmony – because you can make thousands of harmonies with melody – is next. Melody is the least important.” And: “You’re made up of three people: Person A imagines how the piece should be before they play – their ideal, their goal; Person B actually performs it; Person C listens to Person B and if it’s not what A intended, C tells B who makes adjustments. This is a constant aspect of performance.”

And above all his delight in it all: To a student on February 11, 2018 after the first movement of Beethoven’s Sonata No.11, Op.22: “You leave me speechless … I don’t come here to be blown away but when I am, it’s a great pleasure.” A few minutes later, the student smiled as she played the second movement accompanied by Fleisher’s left hand at the top end of the piano.

To experience Fleisher’s inimitable approach, watch his March 31, 2004 masterclass on YouTube from Weill Recital Hall, Carnegie Hall, with the 17-year-old Yuja Wang playing Schubert’s Sonata No.19 D958 when she was a student at the Curtis Institute.

Paul Ennis is the managing editor of The WholeNote.