Toronto concertgoers will have a rare opportunity on Saturday, October 6 at 8pm at the Betty Oliphant Theatre on Jarvis Street. Quebec-born composer Linda Bouchard isn’t often found in Toronto and performances here of major works by this significant Canadian composer are rare. New Music Concerts’ artistic director Robert Aitken decided to address this by mounting a production of her 2011 multimedia work, Murderous Little World.

Toronto concertgoers will have a rare opportunity on Saturday, October 6 at 8pm at the Betty Oliphant Theatre on Jarvis Street. Quebec-born composer Linda Bouchard isn’t often found in Toronto and performances here of major works by this significant Canadian composer are rare. New Music Concerts’ artistic director Robert Aitken decided to address this by mounting a production of her 2011 multimedia work, Murderous Little World.

Bouchard, based in San Francisco for more than 20 years, has had an international career in her multiple roles as composer, conductor, artistic director and all-around artistic instigator and visionary. The list of her awards and prizes is a long one, with recognition coming from Canada, the USA and Europe. Given her impressive credentials, it’s a bit surprising that her work is not presented here more often.

Murderous Little World was commissioned in 2004, developed over many years and finally premiered in 2011 by Bellows and Brass, a Toronto-based trio comprised of Guy Few (trumpet and piano), Joseph Petric (accordion) and Eric Vaillancourt (trombone) at a concert in the NUMUS series in Kitchener-Waterloo. Organized around poetry by the internationally recognized Canadian poet, Anne Carson, the work, in the words of the composer, “brings together gifted artists from different experiences to create a new evening-length multimedia performance that fuses music, poetry, theatre, video art and lighting.”

In her program note, Bouchard says that the poems of Carson, “conjure up a textured universe of ‘little worlds’ that span continents and ages of human existence. Carson’s phrases seem to be made up of fragments or artifacts and point to individuals’ searching for truth against waves of corruption and cruelty.” And as often happens when two creative artists intersect, the meeting of poetry and music creates a synthesis. Bouchard says: “The musical and dramatic response to each poem is unique, with each selection having an individual voice expressed through specific vocals – i.e. whispered, slow recitation, fully voiced, in a range of emotional pitches and vocal styles. At the same time, the three musicians/actors play live and move around the stage creating different dramatic interplay with the visuals.”

New Music Concerts’ October 6 performance of Murderous Little World will be the tenth time the work has been staged. I have witnessed it in an earlier performance, and found it to be a truly remarkable experience, unique and unforgettable. I cannot emphasize enough what a great opportunity this is for people to hear and see such an incomparable work.

Bouchard’s return to Toronto for this presentation reminds me that she and I both made life- and career-shaping moves back in the year 1977. This is when Bouchard decided to attend Bennington College in Vermont, USA to study with another Canadian ex-pat, the highly original, one-of-a-kind composer, Henry Brant (1913–2008). He would shape her artistic approach so deeply, his influence continues to the present. Bouchard said of her work with Brant: “Henry’s influence on me was very profound. He was a true mentor. I cannot tell how much his aesthetic rubbed on mine, but his sense of ethics, his commitment to the craft of being a composer, his professionalism was very much part of his teaching. He had a strong opinion on absolutely everything. Sometimes it was very disconcerting, because it seemed to make the world black or white, and then one day, in the composition class, out of the blue, we’d spend the entire class discussing the difficulty of knowing what is right when you write music.

“I remember being acutely aware that I was in the presence of a very special, unique individual. He was powerful and at times very difficult; it was all worth the work though. For example, for a private lesson, you needed to show up with a score copied in ink. He wanted you to be very committed to what you showed him. Nothing just sketched out quickly and half conceived; he wanted none of this. I remember a few years after having studied with him realizing that I was just starting to understand his orchestration concept. I had kept my notes and kept reading them … It took a while for his true teaching to be absorbed I think... I had gone to Bennington College to study with him, I had heard about him and it was a complete random decision in a way. Amazing how these things happen.”

“I remember being acutely aware that I was in the presence of a very special, unique individual. He was powerful and at times very difficult; it was all worth the work though. For example, for a private lesson, you needed to show up with a score copied in ink. He wanted you to be very committed to what you showed him. Nothing just sketched out quickly and half conceived; he wanted none of this. I remember a few years after having studied with him realizing that I was just starting to understand his orchestration concept. I had kept my notes and kept reading them … It took a while for his true teaching to be absorbed I think... I had gone to Bennington College to study with him, I had heard about him and it was a complete random decision in a way. Amazing how these things happen.”

For my part, 1977 was the year that I decided to propose to CBC Radio that we should create a national network contemporary music program that would bring Canadian listeners a weekly overview of the world of contemporary music. The program that resulted from this pitch was called Two New Hours, and it ran from 1978 to 2007 on CBC Radio Two, producing original Canadian musical content, broadcasting world premieres from concerts from across Canada as well as important premieres by international composers from the major international contemporary music festivals.

By the time Bouchard completed her work at Bennington and had moved to New York, where she based her composing and conducting activities for 11 years, our Two New Hours broadcasts had gained a large listenership for such specialized programming, and a corresponding increase of support from CBC Radio. Broadcasts of concerts presented by the many new music groups around Canada formed a large part of our programming, and Toronto’s New Music Concerts was well represented. Other groups, such as Vancouver New Music, New Works Calgary, Groundswell in Winnipeg, Esprit Orchestra and Soundstreams in Toronto, the Newfoundland Sound Symposium and of course the Société de musique contemporaine du Québec (SMCQ) and the Ensemble contemporaine de Montréal (ECM) also appeared regularly, and many others, as more organizations were created. By the time I first met Bouchard, in the early 1990s, she was already a mature composer with a strong, individual artistic personality.

The music of both Henry Brant and Linda Bouchard was included in the mix of programming we presented. One notable example was in 1990, when we broadcast New Music Concerts’ performance of the Canadian premiere of Brant’s Inside Track, a so-called “spatial piano concerto,” in which the 16 players accompanying the onstage piano soloist (Ivar Mikhashoff) were positioned around the concert hall. Among those spatially deployed performers was a very young soprano, Barbara Hannigan, who was still in school at the time. Our broadcast would be her CBC network radio debut. Needless to say, Ms. Hannigan, now an international celebrity, has come a long way since then. Incidentally, in 2008 this recording was leased by an American label, Innova Recordings, and included in Volume 8 (Innova catalog # 415) of its nine-volume Henry Brant Collection.

Bouchard served as composer-in-residence with the National Arts Centre Orchestra (NACO) from 1992 to 1995. During this time, she arranged for the NACO to invite Brant to Ottawa for performances of several of his works. Among these was the world premiere of his Concord Symphony (1994), an orchestration of Charles Ives’ Concord Sonata. The performance was recorded by CBC Ottawa and broadcast on Two New Hours.

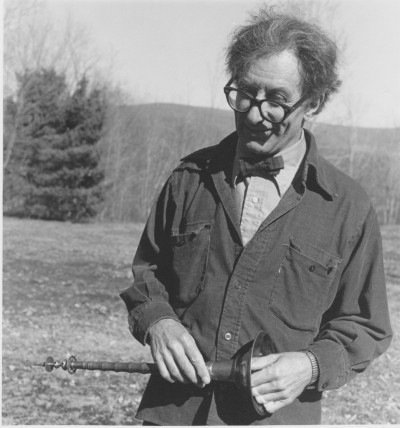

The last time Brant visited Toronto was in 2002, when New Music Concerts gave the world premiere of a work they commissioned, Ghosts and Gargoyles, for multiple, spatially disposed flutes and drum kit. In the interview for the Two New Hours broadcast, Brant emphasized two points: the first was to stress the importance of the music of Ives, not only to his own training and formation, but to the understanding of 20th-century music as a whole. The second point was that he had always considered himself a Canadian composer, even though he and his family left Canada to live in the USA when he was just

16 years of age.

I asked Bouchard to compare her own history to Brant’s. She said, “I am a Canadian composer. I never called myself an American composer, I believe people always perceive me as a Canadian composer, my resume always says that I am a Canadian composer. I actually left as a Quebec composer in my teens but as the years passed, I started to refer to myself as ‘Canadian.’ I did live most of my life in the US, it is true, but as a Canadian composer. It is different –despite the fact that Henry considered himself a Canadian composer – probably because he was proud of his origins – he was considered an American composer.”

David Jaeger is a composer, producer and broadcaster based in Toronto.