![]()

Of late, the topic of mentoring has been on my mind. Your Dictionary defines a mentor as “someone who guides another to greater success,” but one of my favourite quotes on this topic comes from flutist and composer, Robert Aitken: “You can only teach a person two things: how to listen, and how to teach themselves.” Particularly in this latter sense, I have experienced the joys and benefits of being mentored at various points of my life, as well as opportunities to “pay forward” what I have learned.

Of late, the topic of mentoring has been on my mind. Your Dictionary defines a mentor as “someone who guides another to greater success,” but one of my favourite quotes on this topic comes from flutist and composer, Robert Aitken: “You can only teach a person two things: how to listen, and how to teach themselves.” Particularly in this latter sense, I have experienced the joys and benefits of being mentored at various points of my life, as well as opportunities to “pay forward” what I have learned.

Particularly memorable, in the former category were my high school band teacher, my graduate school advisor, my trainer as a new recruit at CBC Radio in 1973, and Glenn Gould, whom I worked with often in the ensuing years.

Then, as my professional career developed, one detail of my personal history seems to have forecast how my own involvement in the role of mentor would evolve. In 1969, while still a university student, I had the good fortune to be named as a Fellow by what was then the Woodrow Wilson National Fellowship Foundation (now The Institute for Citizens & Scholars). The panel of examiners for the Foundation was charged with the task of finding scholars entering graduate schools, whom they felt possessed the potential to become outstanding future teachers. I suppose, in retrospect, those perceptive examiners were on to something, although teaching “on the job” has always come naturally for me rather than as a formal profession.

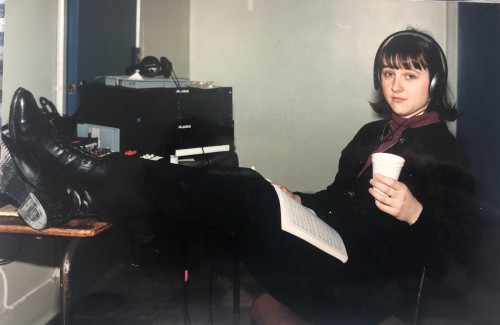

It was during my 40 years as a music producer for CBC, that, with the passage of time, I began to find myself in the role of mentor rather than mentee. There were innumerable opportunities to share my knowledge, skills and experience with colleagues, especially those in the early stages of their own careers, as I had been when I arrived. I found myself delighting in introducing eager young colleagues to programming concepts and methods, and in enabling them to make productive and prudent choices. One of my broadcasting protégés, Stephanie Conn, describes the process as “being given the feeling that we were legitimate producers-in-training and part of the music community, and thus being enabled to grow into just that.”

One of the things I learned early on was that the process of broadcast content production is inherently teamwork, so the key to success is putting the best teams together. The ability of teams to focus effectively on the project’s agreed standards largely determines success in making meaningful content. This seems like common sense, but in reality, actually finding gifted team players and motivating them to join in the effort to make exceptional outcomes, is no small task. Among others, I think of someone like a young recording engineer named Dennis Patterson who was one of the people I had the chance to bring into my production teams, beginning in the mid-1990s. Patterson has worked steadily at his craft, and several of the recordings he engineered have won a variety of prestigious awards, including several JUNOs.

One of the things I learned early on was that the process of broadcast content production is inherently teamwork, so the key to success is putting the best teams together. The ability of teams to focus effectively on the project’s agreed standards largely determines success in making meaningful content. This seems like common sense, but in reality, actually finding gifted team players and motivating them to join in the effort to make exceptional outcomes, is no small task. Among others, I think of someone like a young recording engineer named Dennis Patterson who was one of the people I had the chance to bring into my production teams, beginning in the mid-1990s. Patterson has worked steadily at his craft, and several of the recordings he engineered have won a variety of prestigious awards, including several JUNOs.

Fast forward, then, to 2020, when the plans of every single performing arts organization were brutally rendered void and radical adjustments to plans and well-established ways of thinking have become necessary just to survive. In this context the hierarchical relationship between mentor and mentee goes out of the window; mentorship becomes a team sport, with the ball being passed around as the situation demands.

Fast forward, then, to 2020, when the plans of every single performing arts organization were brutally rendered void and radical adjustments to plans and well-established ways of thinking have become necessary just to survive. In this context the hierarchical relationship between mentor and mentee goes out of the window; mentorship becomes a team sport, with the ball being passed around as the situation demands.

I was given the exhilarating opportunity to work in one such team, when Michael Hidetoshi Mori, artistic director of Toronto’s Tapestry Opera (no stranger to mentoring himself) approached me to participate in one such radical readjustment to a well-set plan. Mori had already put a team in place for the remount of their successful production of the chamber opera, Rocking Horse Winner. Based on a story by D. H. Lawrence, libretto by Anna Chatterton with music by Gareth Williams, the opera was originally produced for the stage by Tapestry in May 2016. It had won five Dora Mavor Moore Awards and looked like an ideal remount candidate. Cast, chorus and instrumentalists had been booked for the spring and summer to rehearse and stage a fresh updated version of this proven work.

I was given the exhilarating opportunity to work in one such team, when Michael Hidetoshi Mori, artistic director of Toronto’s Tapestry Opera (no stranger to mentoring himself) approached me to participate in one such radical readjustment to a well-set plan. Mori had already put a team in place for the remount of their successful production of the chamber opera, Rocking Horse Winner. Based on a story by D. H. Lawrence, libretto by Anna Chatterton with music by Gareth Williams, the opera was originally produced for the stage by Tapestry in May 2016. It had won five Dora Mavor Moore Awards and looked like an ideal remount candidate. Cast, chorus and instrumentalists had been booked for the spring and summer to rehearse and stage a fresh updated version of this proven work.

With rigid pandemic restrictions suddenly introduced last March, Mori faced the prospect of cancelling the entire production. As he describes it: “A combination of valuing the work of artists and making every dollar count are key to Tapestry’s ethos. Like everyone, we had to make some hard decisions. Our first step was to ask artists if they were okay with us honouring the full amount of their contracts, but being open to new ways of spending it.”

With that buy-in achieved, they began with a workshop of the piece, focusing on how online collaboration could happen. Music director Kamna Gupta prepared video and audio conducting tracks. Stéphane Mayer created piano tracks on Tapestry’s Bösendorfer Imperial Grand and, later on, a coaching track for difficult passages that included cues like breathing – something that would normally be followed in person. Mori, as director, was able to go into much greater detail than usual with table work, the time spent with actors focusing solely on character development and plot arc. And they collaborated with their orchestra to record tracks to Gupta’s conducting video.

At this point, as Mori says, the project took a decisive turn. “In doing all of this and stretching our creativity for collaboration, we discovered that deep and musical rehearsals were happening, giving us the confidence to say that we could record an audio album, and that layering as part of the recording process would afford us some creative possibilities in storytelling.”

As a result, in May 2020, Dennis Patterson and I were asked to work with Tapestry to produce a commercial recording of the opera at Tapestry’s Ernest Balmer Studio in Toronto’s Distillery District. We met via Zoom with Mori’s team and determined that we would be able to build the recording from the ground up, multi-tracking four performers at a time over a two-week period, following COVID safety protocols. Each layer of the recording would be complete and edited in time for the next layer, starting with the instruments and ending with the cast principals. In addition to Gupta’s video conducting tracks, live conducting was added when needed, in order to provide ongoing interpretive feedback. Gupta, who was in New York City, was channelled in live to the sessions via Source Connect Now software. Patterson took care at every stage of the recording to create a “real life” monitor mix for the performers, enabling them to deliver a true, believable performance, rather than a simple execution of the notes.

As a result, in May 2020, Dennis Patterson and I were asked to work with Tapestry to produce a commercial recording of the opera at Tapestry’s Ernest Balmer Studio in Toronto’s Distillery District. We met via Zoom with Mori’s team and determined that we would be able to build the recording from the ground up, multi-tracking four performers at a time over a two-week period, following COVID safety protocols. Each layer of the recording would be complete and edited in time for the next layer, starting with the instruments and ending with the cast principals. In addition to Gupta’s video conducting tracks, live conducting was added when needed, in order to provide ongoing interpretive feedback. Gupta, who was in New York City, was channelled in live to the sessions via Source Connect Now software. Patterson took care at every stage of the recording to create a “real life” monitor mix for the performers, enabling them to deliver a true, believable performance, rather than a simple execution of the notes.

We were, in effect, reimagining the opera in a purely sonic world, learning from each other as we went. Post-production editing, mixing and effects took another month, but finally, by early fall, we had our performance.

Tapestry Opera’s recording of Rocking Horse Winner was released in time for it’s premiere network broadcast, December 26, 2020 on CBC Music’s Saturday Afternoon at the Opera, and is now available to the public on bandcamp at tapestryopera.bandcamp.com/releases.

“We needed to be brave and find solutions that would keep us working, learning how to succeed amid restrictions, Mori says. “The silver lining is that this worthy production would have seen a couple thousand audience members live, but its broadcast reached over 300,000 across Canada and the world!”

Quite a different mentoring challenge came my way when a student of mine, Ruby Turok-Squire, who sings with the English vocal octet, Aeterna Voices, based in Leamington Spa in the English Midlands, got in touch. I had composed a setting of the famous W. B. Yeats poem, He Wishes for The Cloths of Heaven, for the group early in 2020; she now wanted to let me know the group had decided to make their debut recording, to be titled The Cloths of Heaven, and to ask if I would guide the process from a distance.

Quite a different mentoring challenge came my way when a student of mine, Ruby Turok-Squire, who sings with the English vocal octet, Aeterna Voices, based in Leamington Spa in the English Midlands, got in touch. I had composed a setting of the famous W. B. Yeats poem, He Wishes for The Cloths of Heaven, for the group early in 2020; she now wanted to let me know the group had decided to make their debut recording, to be titled The Cloths of Heaven, and to ask if I would guide the process from a distance.

Suddenly our conversations, previously largely centred on the topic of choral text-setting, shifted to recording techniques, microphone characteristics, and how to run a recording session. The recording was made last summer at the spectacular Gothic church, All Saints, in Leamington Spa, and will soon be released online.

My summer of 2020 was, in fact, filled with a seemingly endless series of projects, both large and small in scale, and covering a vast range of repertoire. All were by people pivoting to working in remote mode, most, if not all, performing their parts from home. All required coordination in innumerable different ways and for different reasons. All developed their own flow.

With the U.S.-Canada border closing, Canadian cellist Arlen Hlusko, a graduate of the Curtis Institute of Music, and a member of New York’s famed Bang on a Can All-Stars, returned to her home village of Lowville, Ontario. Hlusko’s creative solution to relative isolation was to act as a self mentor: producing and learning from regular webcasts of her own live solo cello performance.

With the U.S.-Canada border closing, Canadian cellist Arlen Hlusko, a graduate of the Curtis Institute of Music, and a member of New York’s famed Bang on a Can All-Stars, returned to her home village of Lowville, Ontario. Hlusko’s creative solution to relative isolation was to act as a self mentor: producing and learning from regular webcasts of her own live solo cello performance.

I connected with her, impressed by her mastery of the cello, and offered to send her music. She hatched the idea of inviting composers from around the world to collaborate with her to create miniature compositions for solo cello, written for Instagram (hence the minute-or-less limit.) The 20 composers who responded came from Australia, Brazil, Canada, Kosovo and the United States; in each case, Hlusko and the composer corresponded, discovering common interests upon which the works were based. All of them had online premieres on Hlusko’s @celloarlen Instagram, as well as live performances on her webcasts in her regular Saturday afternoon series, Live from Lowville with Love. I ended up creating three miniature pieces, solo cello compositions based on works by Scottish poet, David Cameron, now based in Belfast, with whom I had collaborated in another project. An album release will follow.

Looking back at the overall legacy of the content I have been involved in producing, I find it immensely reassuring that those involved have by and large been populated with people with open minds, eager, as Robert Aitken described it, to continue to learn. That kind of reflexive mentoring has never been more important than now.

David Jaeger is a composer, producer and broadcaster based in Toronto.