The explosion of Canadian artistic creativity that led up to and accompanied the Canadian centennial celebrations in 1967 spawned ripples that continued for years, if not decades. In addition to the more than 2000 artistic infrastructure projects that the federal Centennial Commission created, there were also dozens of original musical works commissioned, by various bodies including CBC Radio, to celebrate the milestone. Some of these have remained in the canon of Canadian classical repertoire, such as Norma Beecroft’s The Living Flame of Love, Harry Freedman’s Rose Latulippe, Jacque Hétu’s Woodwind Quintet, Barbara Pentland’s Suite Borealis, Murray Schafer’s Requiems for the Party Girl, and Harry Somers’ Evocations. In December 1967 the Canadian Music Centre (CMC) published a comprehensive catalogue of nearly 200 of these new works. RCA Victor collaborated with the CBC’s international service, Radio Canada International (RCI), to create a centennial edition LP series, Music and Musicians of Canada, which ran to 17 volumes. Other labels, such as Columbia, also released Canadian classical works, although less numerous than the RCA/RCI collaboration.

The explosion of Canadian artistic creativity that led up to and accompanied the Canadian centennial celebrations in 1967 spawned ripples that continued for years, if not decades. In addition to the more than 2000 artistic infrastructure projects that the federal Centennial Commission created, there were also dozens of original musical works commissioned, by various bodies including CBC Radio, to celebrate the milestone. Some of these have remained in the canon of Canadian classical repertoire, such as Norma Beecroft’s The Living Flame of Love, Harry Freedman’s Rose Latulippe, Jacque Hétu’s Woodwind Quintet, Barbara Pentland’s Suite Borealis, Murray Schafer’s Requiems for the Party Girl, and Harry Somers’ Evocations. In December 1967 the Canadian Music Centre (CMC) published a comprehensive catalogue of nearly 200 of these new works. RCA Victor collaborated with the CBC’s international service, Radio Canada International (RCI), to create a centennial edition LP series, Music and Musicians of Canada, which ran to 17 volumes. Other labels, such as Columbia, also released Canadian classical works, although less numerous than the RCA/RCI collaboration.

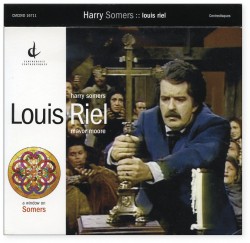

Harry Somers’ and Mavor Moore’s opera Louis Riel was arguably the crowning achievement among all this creative activity. The opera was produced by the Canadian Opera Company in 1967, with the support of the Floyd Chalmers Foundation, and remounted in 1968. In 1969 Riel was produced for national viewing by CBC Television and this version is now available on DVD through the CMC’s Centrediscs label. And of course, this year’s new production by the COC, premiering on April 20, stands tall among the many Canada 150 projects.

All that creative fury in 1967 was somewhat lost on me, as I was, at the time of the Canadian centennial, an undergraduate music student at the University of Wisconsin (UW) School of Music in Madison. But then, while prowling the UW music library, I discovered a shiny-new, complete collection of that very same Music and Musicians of Canada series, where I first heard the music of Somers, Freedman, Pentland, Schafer, John Weinzweig and other Canadian composers. When, in 1970, a Woodrow Wilson International Fellowship aided my choice of the University of Toronto Faculty of Music for graduate study, I realized I would almost certainly meet these, to me, already iconic composers.

The centennial euphoria had died down just a bit when I walked into the University of Toronto Electronic Music Studio (UTEMS) for the first time, in 1970. It wasn’t long before I met flutist/composer Robert Aitken, whose electronic composition, Noesis, was included in a famous Folkways LP, also released in 1967, showcasing UTEMS. This was also the studio in which Somers, together with engineer Lowell Cross, had created the electronic music episodes that appear at various dramatic climaxes in Louis Riel. Beecroft created her mixed media composition, Piece for Bob (commissioned by CBC Radio and composed for Bob Aitken,) at UTEMS as well. It was a facility that was literally dripping with history. Every major composer of the time who included electronic music in their musical language walked through those doors.

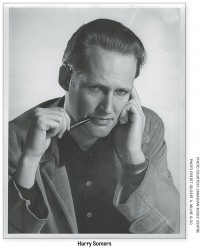

It was at this time in the early 1970s that Aitken and Beecroft were working to launch New Music Concerts, an organization that remains one of the leading contemporary music presenters in Canada. And it was through New Music Concerts that I first worked directly with Harry Somers. In 1975, the same year that Louis Riel was revived by the COC, New Music Concerts presented the premiere performance of a work they had commissioned, Somers’ Zen, Yeats and Emily Dickinson. This is a major work of theatrical music (as opposed to music theatre), in which musicians interact with stage actors who, in turn, deliver passages of text compiled from Zen writings, and poetry by William Butler Yeats and Emily Dickinson. In the course of making the recording of the work, and then preparing its presentation on the CBC network Radio program, Music of Today, Harry and I discovered we had affinities in our respective approaches to music and broadcasting. We agreed that we should meet again in the near future and discuss some innovative programming ideas.

In fact, it took more than a year for the meeting to take place, and rather than a meeting, it turned out to be a production. Harry called and asked if I could book a studio and engineer for the “meeting.” He arrived with a large binder filled with sheets containing what appeared to be some sort of graphic notation. Without much conversation, we made our way to the studio. Harry went in to the microphone, as if he meant to record a statement. But instead of speaking, he began with long, drawn-out breaths, repeating several times with contrasting shape and inflection. He gradually transformed these to more voiced sounds, with occasional bursts of pops, shouts, growls and a wide range of vocal effects. Nearly 20 minutes later he returned to the breathing sounds and eventually fell silent. Harry possessed a marvellous, sonorous voice, and he made very effective use of it.

Harry had just given a performance of a work that he had composed for the American vocalist, Cathy Berberian (1925-1983), titled Voiceplay. It had been commissioned by John Peter Lee Roberts, the head of CBC Radio Music for the CBC Toronto Festival in 1971. Harry felt that Berberian had not taken the work seriously and had not delivered the full contents of the score. By the time our “meeting” was finished, we found we were in possession of an ideal performance of Voiceplay, delivered in the composer’s voice and his own authentic interpretation. When, on January 1, 1978, the new music network series I created, Two New Hours, began its nearly 30-year run on CBC Radio Two, the featured work of our first broadcast was this very production of Voiceplay by Harry Somers.

Harry had just given a performance of a work that he had composed for the American vocalist, Cathy Berberian (1925-1983), titled Voiceplay. It had been commissioned by John Peter Lee Roberts, the head of CBC Radio Music for the CBC Toronto Festival in 1971. Harry felt that Berberian had not taken the work seriously and had not delivered the full contents of the score. By the time our “meeting” was finished, we found we were in possession of an ideal performance of Voiceplay, delivered in the composer’s voice and his own authentic interpretation. When, on January 1, 1978, the new music network series I created, Two New Hours, began its nearly 30-year run on CBC Radio Two, the featured work of our first broadcast was this very production of Voiceplay by Harry Somers.

In fact, notwithstanding his symphonies, concertos, string quartets, sonatas and other instrumental works, Somers’ feeling for the voice was one of his greatest gifts, and it’s only natural that he would grow to be a superb and prolific composer of art song, choral music and opera. While in France in 1960, he had taken time to stay at the Abbey of Solesmes where he studied the practice of Gregorian chant. When he and I undertook to prepare the recording that CBC producer Digby Peers and engineer Brian Wood had made of the 1975 revival of Louis Riel at the Kennedy Center in Washington DC for release on a 3-LP Centrediscs release, Harry handed me an extra tape, right at the beginning of the first editing session. It was the opening song of Act 1, in which an unseen “Folksinger” (as the libretto has it) intones the lines, “Riel sits in his chamber o’ state/Wi’ his stolen silver forks and his stolen silver plate...,” and so on, in a simple, unadorned style. It was beautifully sung and it was clearly Harry’s own voice. He asked me to replace the version from the performance with this preferred interpretation, which he had re-recorded in some unidentified studio. The song was edited into the assembly, and after several months of further editing and sonic enhancement the recording was mastered and released on Centrediscs. The launch of the recording took place at the University of Guelph during an academic conference, “The Image of Riel in Canadian Culture,” in 1985, the centennial of the death of Louis Riel.

In 1988, Somers was commissioned by the COC to write another opera, together with librettist Rod Anderson, Mario and the Magician. It became a a larger work than Riel, and it took four years to complete. In the midst of the writing, Somers told me that being an opera composer was a surefire way to bankruptcy, since the work would be so completely all-consuming, there would be no possibility to accept other commissions. To the best of my knowledge, financial disaster was avoided and soon, after the opera was completed, Somers was once again accepting commissions. One of the first works he completed in 1992 was commissioned by CBC Radio, Of Memory and Desire, for Ottawa’s Thirteen Strings. The work was subsequently performed by Esprit Orchestra and recorded for broadcast on Two New Hours. In his introduction to the broadcast of the work, Somers revealed that the source of the title was from the first stanza of T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land: “April is the cruellest month, breeding/ Lilacs out of dead land, mixing/ Memory and desire, stirring/ Dull roots with spring rain.”

Harry Somers died in 1999 at the age of 73. Shortly after his death, a group of us, under the leadership of Barbara Chilcott Somers and Robert Cram, began recording his music for Centrediscs. This 13-CD/DVD series is called A Window on Somers. Needless to say, most of these recordings were broadcast first on CBC Radio’s Two New Hours. And as it turned out, in a moment of intended symmetry, the very last work heard on the final broadcast of Two New Hours, ten years ago, in March 2007, was a rebroadcast of Somers’ Voiceplay.

David Jaeger is a composer, producer and broadcaster based in Toronto.