Forty years ago, in late 1975, John Peter Lee Roberts, who had been in charge of CBC Radio Music since 1964, left that position, leaving behind an impressive legacy of programming leadership. In his 11 years as Radio Music head, Roberts had commissioned 160 new works by Canadian composers. Among these was R. Murray Schafer’s Apocalypsis, now well known from its revival in this year’s Luminato Festival. Originally commissioned as a 60-minute choral work for the Elmer Iseler Singers, the work that Schafer delivered was twice that length and much more complex and ambitious, incorporating 12 choirs, soloists, sound poets, orchestra, electronics and even mime artists.

Forty years ago, in late 1975, John Peter Lee Roberts, who had been in charge of CBC Radio Music since 1964, left that position, leaving behind an impressive legacy of programming leadership. In his 11 years as Radio Music head, Roberts had commissioned 160 new works by Canadian composers. Among these was R. Murray Schafer’s Apocalypsis, now well known from its revival in this year’s Luminato Festival. Originally commissioned as a 60-minute choral work for the Elmer Iseler Singers, the work that Schafer delivered was twice that length and much more complex and ambitious, incorporating 12 choirs, soloists, sound poets, orchestra, electronics and even mime artists.

This commission gave Schafer an opportunity to proclaim his artistic vision to the nation via network radio, and to the world, through international program exchanges with public broadcasters in other countries. It was perhaps the most grandiose of those numerous commissions, but it shared the same objective as those offered to a wide range of Canadian composers, from Violet Archer, Norma Beecroft and Jacques Hétu to Ann Southam, Harry Somers and John Weinzweig. This was a way for the CBC to fulfill the objective, as defined by the Broadcasting Act, to “encourage the development of Canadian expression by providing a wide range of programming that reflects Canadian attitudes, opinions, ideas and artistic creativity.”

Roberts, and those leaders of the Radio Music department who preceded him, held the authority and the responsibility to grant commissions to those Canadian composers they felt would best fill the needs of programming. The CBC Archives show that they commissioned hundreds of new works in a wide range of genres and styles between 1938 and 1975, many of them, such as Somers’ Gloria (1962), becoming popular enough to be designated “Canadian Classics.”

The impact of these commissions was significant, firstly on the lives and careers of the composers who received them – not only did they provide income and national broadcasts on the network – but furthermore as expressions of Canadian musical styles and new directions in composition in this country.

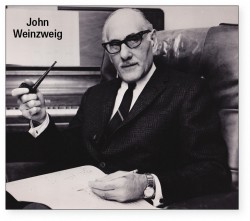

Ironically, by the time Schafer’s Apocalypsis was given its premiere in 1980, John Roberts had moved on in his career, becoming director general of the Canadian Music Centre. Following his departure, authority and responsibility for commissioning original music was passed to the program makers themselves. The argument was that if this content was intended to enhance programming, then the programmers themselves would know what would work best. This significant change allowed music producers to initiate programs based on newly created works tailored to their needs. I experienced this firsthand, when my former composition teacher at the University of Toronto, John Weinzweig, aka The Dean of Canadian Composers, sat down in my office in 1976 with a proposal to create a song cycle for the program I produced at the time, Music of Today. The result of this collaboration was Weinzweig’s Private Collection, written for the young, emerging soprano, Mary Lou Fallis. I remember John telling me that she was “pretty hot stuff” as a performer, besides being an excellent singer.

Private Collection, the first work I had commissioned as a program producer, was broadcast on March 12, 1978, a day after Weinzweig’s 65th birthday. It was, in fact, not heard on the show it was commissioned for, but on a new program, Two New Hours, which we had created with the support of Robert Sunter, who had succeeded John Roberts as the head of Radio Music.

Sunter saw his role differently than his predecessors; his style of leadership emphasized enabling his staff to make creative decisions. We were empowered to make our own programs with the artists we felt would make the greatest impact on listeners. In the exercising of this creative freedom we were able to partner with all the elements of the musical community – motivating and engaging with them. It was this process that I eventually found most satisfying in my work as a broadcaster.

The challenge of developing emerging Canadian composers was an equally important, if not greater mission, for our Two New Hours production team as the opportunity to make programs with established composers such as Schafer, Somers and Weinzweig,. Clearly any production that commissions new works declares its vision of the future. To do so with the younger generation of creative artists was to start a new chapter in our cultural life.

Here are three examples: In 1978, the 30-year-old composer Marjan Mozetich complained that he was fed up with musical modernism and declared his intention to do something about it. We offered him a commission for Two New Hours to prove his point. The work he created, a delightfully tonal and exuberant composition titled Dance of the Blind, did more than offer a new approach. It was, for Mozetich, a watershed composition that strikingly displayed a new romantic, accessible style that defined his artistic voice. Mozetich said that the opportunity to write this piece for the CBC gave him the chance to clearly define where he wanted to go with his music. “There was no turning back,” he said, after the work was broadcast on the national network. Mozetich added: “If an artist wished to highlight an aspect of their work, this was the moment to do it!”

A young Vancouver-born composer named Alexina Louie had spent the 1970s in Los Angeles, first studying composition and then teaching and trying to find work writing music. But she found few opportunities in Los Angeles for either commissions or performances, and in 1980 she returned to Canada, settling in Toronto. Within months of her return she was offered a CBC commission to compose a work for accordionist Joseph Macerollo, harpist Erica Goodman and percussionist Beverley Johnston. The successful premiere and broadcast of her composition Refuge gave her confidence that she could make a career as a professional composer. It also plugged her into three of the most active performers in the Canadian new music community. “I became a professional in L.A.,” she said. “But returning to Canada provided a whirlwind of opportunity to develop my creativity.”

Brian Cherney was entering mid-career as a composer when Two New Hours was created. He accepted a commission for his String Trio, a work that also set him on a new artistic direction. “I knew the piece had to be damn good and interesting but it sort of developed more sophistication and complexity as it went along in the creative process,” Brian said. “I think that one could say that the commission itself made me feel that I had to be as creative and imaginative as possible, so I tried to be just that. I should say that all of my CBC commissions inspired me to write what I consider to be my best pieces –the String Trio, the Third String Quartet, Illuminations, La Princesse lointaine.”

Forty years ago, when Sunter succeeded Roberts at CBC Radio Music, CBC Radio Music had positioned itself at the very centre of an astonishing creative storm. The musical legacy that remains from that period is a rich one. These examples should encourage current instigators of commissioning projects to see that their investment in new works shapes the future of music.

David Jaeger is a composer, producer and broadcaster based in Toronto.