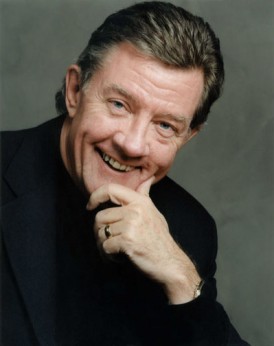

After 37 years as conductor of Kitchener-Waterloo’s Grand Philharmonic Choir, Howard Dyck is stepping down at the end of this season. And as he prepares for a January performance of Elgar’s The Dream of Gerontius, lovers of choral music can celebrate three specific aspects of this down-to-earth, Manitoba-born maestro: his voice, and his two arms.

Dyck’s smooth and affable baritone voice helped make him an ubiquitous sonic presence on CBC radio for over 30 years, hosting Mostly Music from 1976 to 1979, Saturday Afternoon at the Opera from 1987 to 2007, and the programme that he’s perhaps most identified with – Choral Concert, from 1980 to 2008. This last programme in particular has been one of the CBC’s most solid and high quality offerings. Dyck and his producer (and fellow conductor) Robert Cooper presented a show that illuminated not only the wide range of choral achievement in Canada, but featured broadcasts and recordings of the highest quality from all over the world (Choral Concert continues to run every Sunday morning, with new host Peter Togni).

As for his arms, Dyck has been raising them in the service of Canadian choral performance for as long as he’s been broadcasting. Powered by his musical studies in Germany under Martin Stephani at the Detmold Hochschule für Musik, and with Helmuth Rilling at the Internationale Bachakademie in the 1960s, Dyck made his base in 1972 in Waterloo as conductor and artistic director of the Kitchener-Waterloo Philharmonic Choir, now known as the Grand Philharmonic Choir. Although the “K-W Phil” was his principal ensemble, Dyck conducted at various times the Kitchener Bach Choir, London Pro Musica, the Stratford Concert Choir and the Bach-Elgar Choir of Hamilton. He’s done a great deal of international guest conducting, and worked with many distinguished choirs and soloists. As well, he’s played a special part in the launching and fostering of the careers of Canadian vocalists, most notably Ben Heppner and Susan Platts.

In short, Dyck has probably had as distinguished a career as a choral musician and broadcaster as it is possible to achieve in this country. It was a pleasure to interview him and to partake of the incisive, lively mind that powers both voice and arms. Interviewing him by phone, it was as if the host of Choral Concert had simply paused in his broadcast to answer one listener’s questions. Dyck’s voice and manner remains that of a welcoming friend who wears his erudition with ease, and who compels interest and attention without overt demand.

And yet, in dialogue, Dyck displays a firm commitment to his ideas that offsets the ease with which he answers questions. Without dogmatism or snobbery, Dyck makes it clear that he doesn’t subscribe to the idea of qualitative relativism in the arts. Citing Bach as his favourite composer, he makes it clear he believes in the unambiguous musical superiority of the grand tradition of European art-music. There are straightforward ways in which music can be seen as great, or good, or substandard. Bach, Beethoven, Brahms, Mozart, Mendelssohn and Haydn all got there first, and set high standards.

“I feel that the great composers approached religious faith with deep compassion and empathy,” he explains. “Their sympathies lay with the individual and their relationship with God.” As well, he believes that certain elements of both Beethoven’s Missa solemnis and Bach’s B Minor Mass could be considered subversive, even in the midst of what appear to be straightforward assertions of faith. “I hear the Missa almost as cry of despair, the voice of an Enlightenment rationalist who desperately wants to believe, but can’t.” In Dyck’s opinion, Bach’s setting of the Credo text in the B Minor Mass subtly de-emphasizes the dogmatic aspect of the Nicene Creed to stress instead the private, emotional nature of individual faith.

It’s intriguing that he manages to assert these beliefs – which in many circles are grounds for lively dispute – without aggression, loftiness or contempt. There is nothing imperious about Howard Dyck. Rather than dwell on the superiority of his musical tastes, or on his extensive professional achievements, he prefers to speak about the state of choral education in Canada, mentioning six or seven outstanding children’s choirs from across the country. On the subject of young singers, Dyck argues for musical studies as a means to extra-musical literacy and cognitive development. But he’s quick to point out that music is its own reward as well. “It has the same social benefit as team sports. People take pleasure in working alongside one another to do things they couldn’t do alone. Choral music binds people together.”

What have been some memorable musical moments for him? Dyck speaks with affection of Nicholas Goldschmidt and the Toronto Choral Festivals behind which Goldschmidt was the driving force. It was during the 2002 festival that Dyck conducted what he considers to be the highlight of his career, the Canadian premiere of Das Buch mit sieben Siegeln (The Book with Seven Seals) by the neglected and controversial 20th-century Austrian composer Franz Schmidt. While Dyck’s first love is for what is commonly understood to be the classical canon, he’s also done his bit for Canadian composers as well, commissioning and performing works by John Estacio, Leonard Enns, Barrie Cabena, Srul Irving Glick, Imant Raminsh, Derek Holman, R. Murray Schafer and Christos Hatzis.

Why did he choose The Dream of Gerontius as the centerpiece of his final regular conducting season? Dyck’s reasons are practical and timely. He had wanted, he explains, to perform Gerontius with Ben Heppner two years ago, in a performance that would then be repeated in Vancouver. Logistical complications made it impossible for Dyck and Heppner to work together in Waterloo, but Heppner performed the piece in other company in Vancouver. Unfortunately, Heppner fell sick, and had to be replaced in the second half by another soloist. Dyck believes that January’s concert may be the first complete performance of the work that Heppner has given. “It’s perfect for his voice, and will appeal to his sensibilities as well.”

Heppner, a deeply religious man, shares Dyck’s Mennonite background. And the other two soloists also have longtime associations with Dyck: baritone Daniel Lichti has sung numerous performances with the Philharmonic, and mezzo-soprano Susan Platts sang her first professional engagement with Dyck at the age of eighteen. “Howard has been like a musical father for me,” she says. So January’s Gerontius will be in many ways a family reunion.

Gerontius also speaks to the spiritual preoccupations that have driven Dyck’s repertoire choices over the years. Dyck has led the Philharmonic in a tripartite rotation performance of Bach’s two Passions and B Minor Mass each Good Friday since 1984, with a few breaks for the Brahms and Verdi requiems, and the Dvořák Requiem and Stabat Mater. Dyck’s love of Bach stems from his admiration for the composer’s combination of overwhelming craftsmanship – “Bach outdoes them all” – and searing theological insight.

Gerontius also speaks to the spiritual preoccupations that have driven Dyck’s repertoire choices over the years. Dyck has led the Philharmonic in a tripartite rotation performance of Bach’s two Passions and B Minor Mass each Good Friday since 1984, with a few breaks for the Brahms and Verdi requiems, and the Dvořák Requiem and Stabat Mater. Dyck’s love of Bach stems from his admiration for the composer’s combination of overwhelming craftsmanship – “Bach outdoes them all” – and searing theological insight.

Asked about his own beliefs, Dyck characterizes himself simply as a believing Christian. Although he has retained strong ties to his own Mennonite background, he speaks firmly about his general opposition to what he terms right-wing conservatism in religion, a movement and belief-system “that has nothing to do with compassion.” He maintains suspicions about the potential of organized religion to nurture the potential for religious abuse. “Woe to anyone who feels they have the final answer,” he says. His belief is that organized religion must be a forum in which questions can be raised with tolerance and humility, rather than a system in which the few dictate answers to the many.

Dyck speaks quietly of his bond with his mother, and with his wife, Maggie. Growing up as part of a Mennonite farm community in rural south Manitoba, communal singing was so integral to his life that he “can’t remember a time when I didn’t know how to make music.” His mother, an untrained musician, sang until the very end of her life. His first date with Maggie was ushering together at the Winnipeg civic auditorium, during a performance of Messiah. “I’ve been very lucky to have a partner who feels as passionately about music as I do. And she’s also not afraid to tell me if she thinks I’m out to lunch!” This year, they celebrate their 45th wedding anniversary.

He sees the enormous creative potential of the multicultural reality of the country, and loved the wide variation of vocal techniques, cultural traditions and musical styles that characterized the programming in Goldschmidt’s Toronto Choral Festivals. But he also identifies the difficulty of finding support for cultural pursuits, in a country that at this stage lacks a common heritage, one that might help make clear cultural goals and directions.

While Dyck has devoted his life to the work of the European classical tradition, his championship of Canadian and other modern composers makes it clear that he understood his task as that of continuing to build upon a living tradition, rather than simply curating the treasures of the past. He says, “I love the core repertoire. But that core now includes Britten, Orff, Vaughan Williams and John Estacio. And that core will always expand. I’ve made it clear what my own outlook is. I’m not about to tell you what is good music, but the important thing for all of us, as intelligent humans, is that we think about this, that we ask questions of ourselves and each other.”

Perhaps more than anywhere else in the musical pantheon, it is in choirs that these questions are raised. Some groups specialize in European art-music, others in Gospel, others in the spikiest of contemporary music, others in the maintenance and exploration of cultural traditions from varied ethnicities and locales. Many groups – the majority of professional, community, religious and educational choirs – walk the line between all these choices, programming music from many different styles and periods. Music-making that encompasses so many different traditions, goals, pursuits, levels of training and commitment, and sheer numbers of lovers of music, can hardly be characterized as elitist.

A performance by a choir is itself a question: a challenge and an offering to the community around us, a platform upon which we enact, debate and find at least temporary consensus about what constitutes our common heritage. Howard Dyck has done as much as anyone in this country to raise questions and suggest potential answers in this ongoing dialogue.