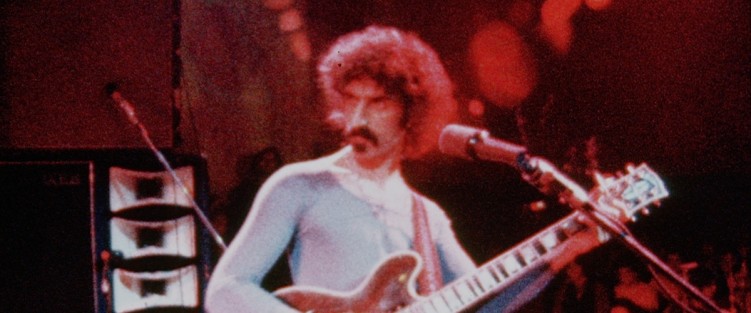

Alex Winter’s new documentary – ZAPPA – about the iconoclastic musician and biting social satirist, Frank Zappa, has much in common with Thorsten Schütte’s absorbing, revelatory 2016 documentary, Eat That Question: Frank Zappa in His Own Words. Zappa’s widow Gail (d. 2015) and son Ahmet (who runs the extensive Frank Zappa estate through the Zappa Trust as co-Trustee) were executive producers of the 2016 film. Ahmet Zappa is also a producer of the new film, which is more about the man than the previous more music-oriented doc. A conservative libertarian who had no use for drugs, Zappa was not how he appeared to be. Nonetheless, given the extent of the Zappa archives, there is much treasure to be found here. Early in the film the man himself takes us on an archival tour – a labyrinth of floor-to-ceiling 8mm movies, audio and videotape of recording sessions, even jam sessions by the likes of Don Van Vliet (Captain Beefheart) and Eric Clapton (neither of which we hear – perhaps they’re being saved for future release).

Alex Winter’s new documentary – ZAPPA – about the iconoclastic musician and biting social satirist, Frank Zappa, has much in common with Thorsten Schütte’s absorbing, revelatory 2016 documentary, Eat That Question: Frank Zappa in His Own Words. Zappa’s widow Gail (d. 2015) and son Ahmet (who runs the extensive Frank Zappa estate through the Zappa Trust as co-Trustee) were executive producers of the 2016 film. Ahmet Zappa is also a producer of the new film, which is more about the man than the previous more music-oriented doc. A conservative libertarian who had no use for drugs, Zappa was not how he appeared to be. Nonetheless, given the extent of the Zappa archives, there is much treasure to be found here. Early in the film the man himself takes us on an archival tour – a labyrinth of floor-to-ceiling 8mm movies, audio and videotape of recording sessions, even jam sessions by the likes of Don Van Vliet (Captain Beefheart) and Eric Clapton (neither of which we hear – perhaps they’re being saved for future release).

Zappa’s early home life was completely without music. His father worked at a gas chemical factory, so his toys were gas masks and his interests concentrated on chemistry – he made gunpowder at the age of six. As a young teenager he read a magazine story about how Sam Goody’s (a major record seller in the 1950s) was able to sell records by Edgard Varèse that were considered too strange for most people to buy. Zappa bought The Complete Works of Edgard Varèse and it changed his life. “I just liked it [the way percussion was playing an integrated melodic part] and couldn’t understand why other people just didn't like it,” he said. There’s an 8mm snippet of him playing Varèse on the harmonica. He had no interest in Mozart or Beethoven, “only in the man who could make music which was that strange.” Hearing Ionisation led Zappa to write orchestral music. Much later, he took to playing Varèse’s Octandre as an encore “because after hearing it, the audience wouldn’t possibly hear another number.”

He taught himself to play blues guitar in high school by listening – sometimes staying up until 3am – to the music of Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown, Guitar Slim, Elmore James, Lowell Fulson and Johnny “Guitar” Watson (with whom he later played). In his mid-teens he was a member of a racially mixed band, The Blackouts, which at the time was considered too radical for the small California town where he lived.

But like those 1950s comic musical geniuses, Ernie Kovacs and Spike Jones, he believed that “if you could get a laugh, that was good.” Bunk Gardner (who played with Zappa’s Mothers of Invention from 1966 to 1969) remembers that there weren’t too many bands that had horns, and certainly not many playing Stravinsky (“which made us really unique”). Zappa was a perfectionist who liked to laugh, Gardner said, “It became our duty to make him laugh.”

Zappa met his future wife, Gail, in 1966; it was literally love at first sight. They married a year later, shortly before their first child, Moon, was born. Later we see Moon at 13 sliding a letter to her father under his studio door. It’s a proposal to work on a song with him. The result was “Valley Girl,” Zappa’s only big hit.

Alice Cooper (signed by Zappa to his new recording company): “Frank never went for the hit record, even to the point of sabotage.” Guitarist Steve Vai, who played with Zappa in the early 90s: “Frank was a slave to his inner ear.”

Percussionist-pianist Ruth Underwood was a Juilliard student who realized after hearing Zappa that she didn’t want to be a timpanist in an orchestra or sit in the back row and wait to play three notes on the triangle. A lifelong devotee to the man and his music who played in his band – “he was a passionate man and loyal to his musicians” – she felt that Zappa’s music was “put on earth for me. Frank’s music will last – it could live in the concert hall.”

Percussionist-pianist Ruth Underwood was a Juilliard student who realized after hearing Zappa that she didn’t want to be a timpanist in an orchestra or sit in the back row and wait to play three notes on the triangle. A lifelong devotee to the man and his music who played in his band – “he was a passionate man and loyal to his musicians” – she felt that Zappa’s music was “put on earth for me. Frank’s music will last – it could live in the concert hall.”

Violinist David Harrington, Kronos Quartet founder and artistic director, who commissioned Zappa: “I always appreciated the fact that he taught himself. I’m reminded of Charles Ives, Harry Partch and Sun Ra, American experimentalists who totally reimagined how music might be heard and might be composed.”

Gail Zappa: “Frank’s measure of success was in how close did you get to the realization of the idea that you first heard. If you get anywhere near it, you could call it a success – most of the time you never even get close because you need to rely on other people [musicians] to get you there.”

Frank Zappa: “All I want is to get a good recording of everything I ever wrote so I can hear it.”

So he rented the Barbican and hired the London Symphony Orchestra with conductor Kent Nagano.

Before his death at 52 in 1993 from prostate cancer, Zappa was acclaimed in the Czech Republic and named the Czech Cultural Representative to the US. His last concert, in 1992 in Frankfurt, Germany, conducting the Frankfurt-based Ensemble Modern playing his own music, garnered a 20-minute standing ovation followed by a single-chord encore.

Zappa released 62 albums during his lifetime; 53 additional albums have been issued since his death.

Zappa is currently available via hotdocs@home or VOD from your favourite source.

Paul Ennis is the managing editor of The WholeNote.