Please click on photos for a larger image.

Now that a few weeks have passed since the final screening of the 2012 edition of the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF), TIFF’s impact is really just beginning. Several of its almost 300 feature films have already opened in theatres with many more to follow in the months ahead. It’s the gift that keeps on giving with a half-life of at least a year. With a number of pre-screenings in addition to the festival itself and post-TIFF openings, I’ve managed to see more than 75 of TIFF’s offerings. What follows is a snapshot of a score of movies in which music plays an intriguing role.

Now that a few weeks have passed since the final screening of the 2012 edition of the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF), TIFF’s impact is really just beginning. Several of its almost 300 feature films have already opened in theatres with many more to follow in the months ahead. It’s the gift that keeps on giving with a half-life of at least a year. With a number of pre-screenings in addition to the festival itself and post-TIFF openings, I’ve managed to see more than 75 of TIFF’s offerings. What follows is a snapshot of a score of movies in which music plays an intriguing role.

Quartet (set to open January 11, 2013 and sure to be a crowd pleaser) is a rarity. Ronald Harwood’s screen adaptation of his 1997 play manages to fuse the acting talents of some of the UK’s finest (and the directorial debut of 75-year-old Dustin Hoffman) with a cornucopia of musical excerpts from Verdi’s La Traviata and Rigoletto, Puccini’s Tosca, G&S’s The Mikado, Rossini’s The Barber of Seville, Haydn’s “Sunrise” quartet and “Military” symphony, a Boccherini string quintet and the Toccata and Fugue in D Minor by Bach. Harwood was inspired by Tosca’s Kiss, Daniel Schmid’s loving documentary depiction of the residents of the Casa di Riposo per Musicisti, which Verdi founded in Milan as a residence for elderly singers who needed material help.

Music percolates everywhere in Beecham House (named after Sir Thomas) with Maggie Smith, Tom Courtenay, Billy Connolly, Pauline Collins and Michael Gambon playing out Bette Davis’ maxim “Old age is not for sissies.” As a group of opera singers preparing for a house fundraiser, their love of life is infectious. And with many of the home’s residents played by musicians, from soprano Dame Gwyneth Jones (unforgettable in “Vissi d’arte” from Tosca) to former BBC Symphony principal clarinetist Colin Bradbury and versatile trumpet player Ronnie Hughes (his resume even includes the Beatles’ “Martha, My Dear”), the quality of the musical content is guaranteed. Be sure to stay through the beginning of the credits where many of the musicians are pictured in their youth.

Even though none of the characters in Terrence Malick’s To the Wonder (his follow-up to the Palme D’Or-winning Tree of Life) are musicians, the film’s musical component rivals that of Quartet. This exploration of love (both sacred and profane) by the masterful collagist of image and sound revolves around a taciturn strong male played by Ben Affleck and two women he loves. One (Olga Kurylenko, whose occasional voiceover chronicles the course of her passion), a foreigner, is drawn to him while holidaying at Mont Saint-Michel (“The Wonder”) in Normandy. The other (Rachel McAdams), an old flame whose prime animus is religion, reconnects with him when he moves back to Bartlesville, Oklahoma.

But to the soundtrack: It’s not only the extraordinary use of Wagner’s “Prelude to Act One” from Parsifal which elevates the Mont Saint-Michel episode – in fact, only Lars von Trier’s alchemy with the prelude from Tristan und Isolde in Melancholia can compare among recent Wagnerian film moments – it’s the way Malick piles on phrase upon phrase with (often) unrecognizable bits of many works, from Haydn’s The Seasons to Respighi’s Ancient Airs and Dances, Suite no. 2, from the second and third movements of Gorecki’s Symphony No. 3 to the third movement of Rautavaara’s Cantus Arcticus and Shostakovich’s Piano Concerto No. 2 to Rachmaninov’s Isle of the Dead. The music gives what we see onscreen depth and purpose.

How music can keep one’s spirit alive is the subject of the delicately told Serbian film When Day Breaks (Serbia’s nominee for Best Foreign Language Film Academy Award), in which the Holocaust unexpectedly enters the life of a retired music professor, warmly played by Mustafa Nadarevic. “As long as this music exists, so shall we,” his father wrote in his last message to his son. The letter was found along with a family photograph and some sheet music in a box in the ruins of the Belgrade fairgrounds more than 60 years after they were buried. The site had been a concentration camp for Jews and Gypsies. As the professor unearths his biological roots he also works on finishing the sheet music, playing it first on the piano, then with his violin student. It’s a bittersweet tune in a minor key with an indelible Hasidic hook. As he investigates his origins on the banks of the Danube where his father had been an exceptional musician who played several instruments, it becomes the film’s theme, literally and figuratively; music not only expresses our deepest feelings, it enables us to overcome suffering.

Recently in Toronto we were fortunate to hear Anne-Sophie Mutter’s vigorous performance of Sofia Gubaidulina’s In tempus presens (“For the present time”) with the TSO. The program notes contained this fascinating quote from the 81-year-old composer: “Just like many 20th century creators, the problem of time concerns me to the greatest extent possible. I am concerned with how time changes in connection with the changing psychological conditions of man, how it elapses in nature, in the world, in society, in dreams, in art.”

In The End of Time (opening December 12), Toronto filmmaker Peter Mettler shifts from concepts of time to an experience of it, which he likens to listening to music. In his mesmerizing documentary he uses images and sound -- the tools he’s most comfortable with – to observe time and make our experience of it palpable (in a good way). Moving from the CERN particle accelerator which creates subatomic particles that haven’t existed since seconds after the Big Bang to filming lava flowing on the Big Island of Hawaii and nature reclaiming the city of Detroit, Mettler fills the screen with thoughts that set us pondering: “In the beginning there was no time, or, time was all there was;” ”In many languages ‘time’ and ‘weather’ are the same word;” “Does Nature have a consciousness or is it a set of circumstances?;” “Technologies don’t save time, they spend it.”

As an ice cream truck ambles the urban ruins of Detroit, Nichols Electronics’ version of Turkey in the Straw turns the image into a yo-yo of time future and past. Mettler uses music by Autechre, Robert Henke and Thomas Koner to animate his images while techno DJ Richie Hawtin (“Plastikman”) distills time down to its basic rhythm. Christos Hatzis’ and Bruno DeGazio’s audio-visual immersive sound and light show, Harmonia, their beautiful Mandala-like depiction of harmonic overtones, concludes the proceedings before Mettler brings his investigation back home on Mother’s Day with an unexpected but timely personal moment.

One of the many things Beethoven did was distill time down to its basic rhythm. In A Late Quartet (opening November 23) writer-director Yaron Zilberman wanted to combine his feelings about family with his love of string quartet music. He thought a string quartet would provide the ideal vehicle to explore the rhythms of parental relationships with those of siblings and married couples. And he also incorporated many aspects of the Guarneri, the Italian and the Emerson quartets into his script. The musical elements of A Late Quartet work well, the melodrama of the metaphorical relationships less so.

Beethoven’s String Quartet No. 14, Op. 131 dominates the film from beginning to end, in performance and as a teaching aid. The Brentano Quartet supplies the soundtrack and the Attacca Quartet appears as Juilliard students. The actors are led by an avuncular Christopher Walken as the cellist who founded the group but whose Parkinson’s diagnosis puts their future in doubt. Philip Seymour Hoffman (2nd violin) and Catherine Keener (viola) have a talented Curtis-trained violinist of their own as a product of their marriage. Mark Ivanir plays the driven 1st violinist who teaches their daughter to get into the mind of Beethoven and buy the proper horsehair to get the right timbre out of a bow, but finds it hard to resist her ardour. Philip Seymour Hoffman talks about Schubert’s last request (to hear the Op. 131 quartet) and how he imagines their quartet playing the last music Schubert would hear on earth. But he has issues of his own that threaten the quartet’s existence.

Curiously, the Brentano Quartet visited Toronto during TIFF for a Music Toronto concert. Two weeks later the youthful Attacca Quartet performed in the same series.

Professionals for only five years, they gave us an upfront insight into the formative years of what may become a lifelong commitment. (In this instance, their enthusiasm occasionally outshone their balance.) Ironically, their name “attacca” refers to the practice of playing musical movements without a break, as Beethoven himself called for in his Op. 131 quartet.

Imagine my surprise when, early in Night Across the Street, the last completed film of the great surrealist filmmaker Raoul Ruiz, his protagonist, Don Celso, looks back on his life and Ludwig van Beethoven appears as a child saying, “I’d like to be a musician. We musicians were put on earth to suffer.” Next we see him conducting his 5th symphony. He goes to the cinema (a Western is showing) with the now youthful Celso while the third movement of his 7th symphony is heard on the soundtrack. Beethoven was Don Celso’s favourite hero so naturally he would be a major part of his life experience.

Christopher Walken convincingly plays against type in A Late Quartet, but in Seven Psychopaths (now in theatres), he pushes his own familiar envelope clear out of its zip code. Written and directed by Martin McDonagh of In Bruges fame, Seven Psychopaths is an entertaining meta-movie where the fourth wall is made of sawdust and much of the action is boosted by a smartly chosen soundtrack by the likes of Townes van Zandt, Hank Williams and Joe Strummer. The plot about scriptwriting, dog-napping and insouciant murder will undoubtedly bring pleasure to many. I would just add this curious note: There are two scenes with a particularly high body count; during the first, in addition to gunshots, the air is filled with Berlioz’s sublime “Strophes” from Romeo et Juliette; the second is muted by a choral excerpt from Orff’s Der Mond (The Moon).

Alexandre Tharaud makes a cameo appearance and plays Schubert and Bach in Michael Haneke’s Amour (opening January 11), which won the Palme D’Or at this year’s Cannes Film Festival. Tharaud plays the star pupil of a pair of now-retired piano teachers whose lives are transformed when the wife suffers a series of small strokes. Elegantly acted by French legends Jean-Louis Trintignant and Emmanuelle Riva (81 and 85, respectively), the way their characters deal with this change in their lives is difficult and provocative yet sublimely conveyed.

In his comedy that centres on a rocky father-son relationship, Mika Kaurismaki’s Road North begins with a performance of Sibelius’ Piano Quintet and ends with one of Schubert’s Sonata for Piano, D894. Finland’s leading film and music icons, Vesa-Matti Loir and Samuli Edelmann play the estranged father and son, the former an old rock ‘n roller, the latter a proper concert pianist. When Loir sings “Autumn Leaves” (in Finnish, while driving), his commanding physical presence totally given over to his sensitive musicality and rich baritone, it’s clear why he’s a star.

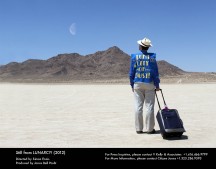

Little did I know when I took my son Simon Ennis to the Kennedy Space Center during a trip to Florida to take in some MLB spring training games that 20 years later he would make a zany and poignant documentary, Lunarcy! (opening February 2013), about people obsessed with the moon. It includes a fully realized portrait of one of the most eccentric, driven characters you will ever see on screen -- Christopher Carson, who wants to be the first person to leave the earth to live on the moon without ever coming back. It also includes an inventive score by Toronto-based composer Christopher Sandes, inspired in part by the early 70s synthesizer stylings of Wendy Carlos.

Lovers of the analog process and Italian horror films of the 1970s known as “giallo” will be pleasantly transfixed by Peter Strickland’s Berberian Sound Studio (opening February 2013). Toby Jones plays a mild-mannered sound engineer whose mind starts playing tricks on him as he edits shrieks and the blood-curdling sounds of vegetables being chopped for a low budget Italian movie studio. All to a spooky soundtrack composed by James Cargill of Broadcast which captures the tone(s) of that bygone era. “I’ve been listening to giallo soundtracks for years and it only just hit me how beautiful and ethereal and spacey they are,” says Strickland. “The composers were involved in musique concrete, free jazz, avant-garde music, so in their work they had this weird parallel between this kind of academia high art and this completely sleazy, b-grade exploitation low art. They did some of their most advanced work for these ?lms.”

Unfortunately, neither Paul Andrew Williams’ Song for Marion nor Ben Drew’s iLL Manors lived up to expectations. Even with the presence of the magnificent Vanessa Redgrave, the former’s conceit of having a group of rowdy seniors sing Sex Pistols’ songs and the like whenever the treacly script flagged was not enough to keep me glued to my seat. And despite the inventive use of Saint-Saens Carnival of the Animals in the opening montage that sets up this rap tale of a drug centric world, the latter film rarely rose to that level again.

And now to a handful of films where familiar music was pointedly used to place the action or in the case of Noah Baumbach’s emotional moving Frances Ha subliminally work in its favour. Frances, which Baumbach co-wrote with his paramour and star, the luminous Greta Gerwig, is a modern fable of a young woman pursuing her artistic dreams in New York City. The soundtrack, filled with snippets of Georges Delerue music from such films as Truffaut’s Jules and Jim and The 400 Blows, Godard’s Le Mepris (“Contempt”) and Philippe de Broca’s arthouse cult classic King of Hearts enhanced the film’s black and white palette while Hot Chocolate’s “Every 1’s a Winner” and David Bowie’s “Modern Love” as well as music by the Rolling Stones, Paul McCartney and Harry Nilsson enhanced what was a delightful moviegoing experience.

Two very fine period pieces, Sally Potter’s Ginger and Rosa, the story of two 17-year-olds, best girlfriends, set in the London of 1962 when Britain was rife with “Ban the Bomb” fervor and Olivier Assayas’ Something in the Air, set in the Paris of 1971, which paints a vivid picture of Parisian youth in the afterglow of May 68, are both set off by telling musical choices.

You can hear Count Basie, Django Reinhardt, Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis, Dave Brubeck and Thelonius Monk punctuating Ginger and Rosa. Syd Barrett, Booker T, Dr. Strangely Strange, Amazing Blondel, Nick Drake, Captain Beefheart, the Incredible String Band, Tangerine Dream and Soft Machine help to vividly recreate an era of politics and love that opened the horizons of a generation.

Philip Seymour Hoffman may once again hear Oscar knocking on his door next year after his expansive, wide-ranging portrait of a fun-loving, booze-guzzling huckster, a cult leader with a gigantic appetite for life and a mysterious bond with a rough hewn WWII vet (Joaquin Phoenix) in Paul Thomas Anderson’s enigmatic but spellbinding The Master (now in theatres). Jonny Greenwood’s score rises to the occasion but it’s Jo Stafford singing “No Other Love” and Ella Fitzgerald’s version of “Get Thee Behind Me Satan” that incisively evoke the early postwar period.

Ella Fitzgerald (clearly a touchstone) sings the title song in Abbas Kiarostami’s Like Someone in Love, as well as “Sophisticated Lady”, two subtle touches that buoy this inscrutable tale of an elderly Japanese literary translator (Tadashi Okuno) whose surprising encounter with a beautiful, young student/prostitute (Rin Takanashi) takes us into unexpected but profoundly enigmatic directions. Kiarostami, a true master, navigates human relationships like no one else.

Finally, two movies in which the performance of music is integral to the plot. The Sapphires is based on the true story of an Aboriginal Australian girl group who entertained the American troops in Viet Nam in 1968. Their Irish manager had to teach the three sisters and their cousin the soul music they sang, but for a few months they all rode the exhilarating entertainment highway. There are huge sociological implications to their feel good story but as we discover as the credits roll, it’s the love of singing that has sustained the lead singer for all the years that elapsed since, a gift that she shared with her own extensive family.

Marc-Henri Wajnberg’s Kinshasa Kids contains many uplifting moments as it chronicles a group of children, abandoned by their parents as witches, who find joy in the performance of music using whatever makeshift instruments they can find to accompany their voices. The euphoria they convey when they chance upon a local performance of Mozart’s Requiem is priceless, as is their excitement over the chance to perform with the legendary Papa Wemba. It’s all about respect for the music, something the Orchestre Symphonique Kimbanguiste, who contribute to the soundtrack, definitely has.