![]()

“No matter how difficult times are, try to remember that everywhere in the world there are a lot of good people and somehow, in the worst times, you meet someone who will help take you away from the danger. Do not forget that, because if you only think of the bad part, you do not have much hope for the future. But I think it is the contrary. All these years, many times I was in danger and there was always someone who would appear and help me and get me out of that danger. I want to thank all the people who helped me in my lifetime when it was difficult.”

“No matter how difficult times are, try to remember that everywhere in the world there are a lot of good people and somehow, in the worst times, you meet someone who will help take you away from the danger. Do not forget that, because if you only think of the bad part, you do not have much hope for the future. But I think it is the contrary. All these years, many times I was in danger and there was always someone who would appear and help me and get me out of that danger. I want to thank all the people who helped me in my lifetime when it was difficult.”

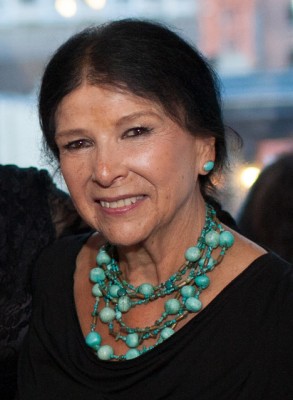

– Alanis Obomsawin

Every two years, the Glenn Gould Foundation convenes an international jury to award the Glenn Gould Prize to a living individual for a unique lifetime contribution that has enriched the human condition through the arts. Alanis Obomsawin, prolific documentary filmmaker, singer-songwriter, visual artist, activist and member of the Abenaki Nation, was chosen as the 13th Glenn Gould Prize Laureate on October 15, by a distinguished international jury chaired by groundbreaking performance artist, musician and filmmaker, Laurie Anderson.

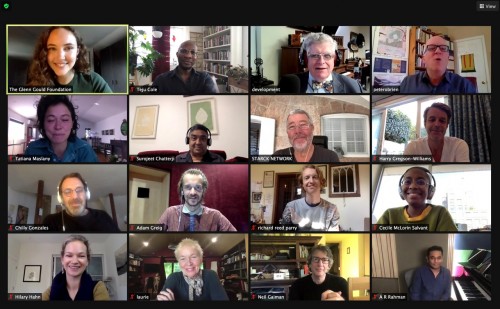

Announced in an emotionally compelling virtual press conference that stretched across the planet, from Chennai, India, to Hollywood, the Glenn Gould Foundation shone a light on the greatest Canadian filmmaker you may never have heard of. Alanis Obomsawin has directed more than 50 films for the National Film Board of Canada, where she has worked since 1967. Her body of work includes the landmark documentary, the internationally acclaimed Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance (1993), the first of four films she made about the 1990 Oka Crisis.

Now 88, she continues to make films. With Jordan River Anderson, the Messenger (2019), she recently completed a film cycle devoted to the rights of Indigenous children. She received the news of winning the Glenn Gould Prize while on set making a new film about a dream she had as a young woman. The main character is a green horse.

“I never expected to win such an honour,” Obomsawin said via video during the press conference. “I am in my village of Odanak in the province of Quebec. This is where I was raised. And this morning I watched the sun rise. It was like a prayer – it is the beginning of life. Our people’s name [Abenaki] means ‘people from where the sun rises, people of the East.’”

At the press conference, former Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, Beverly McLachlin, a board member of the Glenn Gould Foundation and member of the jury of the 12th Prize Laureate in 2018, acted as master of ceremonies, describing how Glenn Gould had passionately believed in the power of music and the arts to transform lives, and how, in that spirit, the aim of the foundation today is to celebrate “artistic heroes.”

At the press conference, former Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, Beverly McLachlin, a board member of the Glenn Gould Foundation and member of the jury of the 12th Prize Laureate in 2018, acted as master of ceremonies, describing how Glenn Gould had passionately believed in the power of music and the arts to transform lives, and how, in that spirit, the aim of the foundation today is to celebrate “artistic heroes.”

Laurie Anderson introduced the jury by saying what a pleasure it had been for her, listening to the jurors’ passionate speeches and insights into the work of the 24 nominees they had to choose from. “I’d like to hear about your thought process,” she said, inviting each of them in turn to speak. Hilary Hahn – Anderson called her “the best violinist in the world, in my opinion, a very sharp juror looking at bigger issues” – had an interesting take on things: “I found this to be [like] an old-fashioned salon in which people share their ideas on art,” Hahn said. “The jurors’ conversations were passionate, informed. I felt honoured to be a part of the discussion ... [In Obomsawin] I see an icon of bravery and resilience; I see her work as an act of love for her community.”

Hahn was one of eight musicians on the 12-person jury, two of whom were Canadians: Richard Reed Parry, core member of Arcade Fire – Anderson talked about his “insight into how culture works in our moment” – and composer Chilly Gonzales, described by Anderson as “an amazing steady, cool presence, a tiebreaker, very skillful.” Gonzales said it felt like chaos at the beginning, seeing the list of nominees. “There was no guidance,” he said. “We had to find our own way.” He credits “our sherpa Laurie Anderson,” the spirit of Glenn Gould and “our spirits. It was inevitable.”

Nigerian-American writer, photographer and art historian Teju Cole: “It’s such an honour to be able to echo what others have said and for people watching this, I want them to understand that this is what it was like to be on this jury, just listening to very thoughtful, very soulful, people… The jury was full of incredibly accomplished people who somehow prioritized the idea of honouring somebody… for the kind of things we would wish to be honoured for ourselves, for the particular values that we would like to come to the surface in our own work … I think the greatest joy and the deepest honour was to arrive at Alanis Obomsawin, who is a beacon for the Abenaki nation, and for the world. In 52 films, in the wonderful album Bush Lady, she exemplifies in a surprising way what we appreciate also in somebody like Glenn Gould, which is fearlessness and intensity combined.”

Not only has Obomsawin documented history – in the classic observational style of the National Film Board of Canada – in some cases, the Oka Crisis, for example, she has been a part of it. In the summer of 1990, Obomsawin spent 78 tense days filming the armed stand-off between the Mohawk people of Kanehsatà:ke, the Quebec police and the Canadian army to create a historical record that gave voice to an Indigenous community.

Jury member Surojeet Chatterji, a pianist and music educator based in Chennai, India, called Obomsawin “a virtuoso … who plays on the fabric of life.”

Composer, singer-songwriter, music producer, philanthropist, jury member A. R. Rahman, also based in Chennai: “Alanis Obomsawin is a name that stands for resistance, persistence and resilience. Her life and her ardour as a creative icon are unique and inspiring over seven decades of chronicling the world through her art. Alanis has chartered a quiet revolution, passionate and powerful. Alanis’ art has always been a medium for social justice. In a world that belongs to all, but continues to sideline many, Alanis takes us beyond the norm, to reclaim history we once lost. At a time where there is more information than actual learning, Alanis guides us with wisdom from another realm, humble, going beyond just the surface.”

Only once, in 2013, when Robert Lepage was named Laureate, did the Foundation award the Prize to an artist not exclusively connected to the music community. You might think that this year’s Laureate would have been the second, but if you do, you don’t know the whole story of the remarkable woman whose artistic life has “enriched the human condition.” Seven years before beginning her work with the NFB, Obomsawin began her artistic life as a singer-songwriter in 1960. Since then, she has toured extensively, her songs – several based on traditional Indigenous melodies – serving as searing portraits of the lives of Indigenous women. A remastered version of her only album, Bush Lady, recorded in 1984, was released in June, 2018. The full effect of her performing skills can be seen in a powerful performance (when she was 85) of Bush Lady (Part 1), on YouTube.

Richard Reed Parry: “It feels like a great privilege to shine a light on that incredible body of work and a lifetime of achievement and I’m so personally thrilled. Besides her incredible films, I am also a massive fan of her music and where her music intersects with her films, uniting the spiritual and the ancestral in a musical way, as well as bringing together so much factual, valuable, sociocultural work in all of her documentary filmmaking.”

Later this year, Obomsawin will also select a young artist or ensemble to receive the $15,000 Protégé Prize.

Jazz singer extraordinaire Cécile McLorin Salvant, who was 2018 GGF Laureate Jessye Norman’s choice for the Protégé Prize that year and was recently named a MacArthur “Genius Grant” Fellow, found it “really inspiring, really fun” to see how the other jury members think, but then summed up her own feelings:

“I just want to reiterate how much of an icon Alanis Obomsawin is. She listens, she is extremely generous in her work and I want to make sure to say the name of this album that she made that is incredible, Bush Lady. I’ll say it three times. Listen to Bush Lady – it will change your life. It changed my life. Watch Mother of Many Children – it will change your life. Watch Christmas at Moose Factory – it will change your life. It will change the way you go through the world with people. It will teach you about a group of people that you probably don’t know about. I am honoured to encounter Alanis Obomsawin’s work and so excited that she is the Laureate this year.”

Paul Ennis is the managing editor of The WholeNote.