Concert Report: Dramatic music a constant at this year’s Luminato

As I made my way through the lobby of the John Bassett Theatre on Saturday, June 24 to find my seat, I was surrounded by Russian speakers excitedly in conversation, waiting for the curtain to go up on the Vakhtangov State Academic Theatre production of Russia’s Uncle Vanya (as part of the 2017 Luminato festival). What a perfect unexpected pre-show start to an evening of classic Russian theatre that I was to review as part of my work as The WholeNote’s music theatre columnist

As I made my way through the lobby of the John Bassett Theatre on Saturday, June 24 to find my seat, I was surrounded by Russian speakers excitedly in conversation, waiting for the curtain to go up on the Vakhtangov State Academic Theatre production of Russia’s Uncle Vanya (as part of the 2017 Luminato festival). What a perfect unexpected pre-show start to an evening of classic Russian theatre that I was to review as part of my work as The WholeNote’s music theatre columnist

“Wait a second,” you say, “Uncle Vanya? But that's Chekhov, right? Slightly turgid, sad, straight plays about people who want to go to Moscow or not sell their Cherry Orchard...right?” “Well, yes,” I reply, “and no.” This company is famous for using the theatrical methods of Meyerhold – large-scale symbolism, mime and music – in their productions, so it does qualify as “music theatre” to some extent. I was interested to see how important music would be to telling the story, as well as what would be different in the Vakhtangov company’s approach, and how it would affect my response.

It took a while to acclimatize to the style and its conventions, which at first were almost alienating, but by halfway to the intermission I was won over and the production began to take hold. From the beginning, the music was a constant. Almost no scene was un-scored or unaccompanied by sound – sometimes in accord with the surface emotion of a scene, but more often expressing what lay beneath – and only rarely was there no music or sound at all, and only for specific effect.

While the text of the play (and the program stated, no word of Chekhov’s writing had been omitted) was spoken in what one would think of as a natural, realistic way, the physical expression of emotion, feelings and relationships was not. At first it seemed strangely presentational and arbitrary, but later it became refreshingly evocative of what the characters were feeling – often the opposite of what they were saying. From Elena throwing herself onto the floor in the middle of the stage or walking across the stage with a silver hula hoop (which naturally folded into the staging), to Vanya’s caressing of Elena’s feet and calves (the only part of her visible from behind a screen), to characters feeling no need to look at each other as they spoke, to the grand mimetic entrances and exits for the professor and his entourage, the physicality of this production was used to powerful, and often disconcerting, effect.

From my reading about Meyerhold I had expected the stylization to have more influence over the speaking of the text, so that was the biggest surprise, and for me a great part of the success of this production. Somehow in this particular combination of words, movement and music, the inner needs and lives of the characters were set free and allowed us to love them and laugh at them at the same time. World theatre criticism and production has finally moved on to a more general acceptance of the fact that Chekhov’s plays are actually meant to be funny (alongside the personal and societal sorrows they depict) but this production was a revelation, the comedy and tragedy so strongly interlaced and exposed to us in the audience that we came to really care about these odd, desperate trapped people, in all their absurdity and flawed humanity.

Until the Lions: Earlier in the festival on June 18, I had the chance to see Akram Khan’s dance production Until the Lions, and in this the music was even more integral. Long before the show itself began there was an almost subliminally present, ominous wind-like soundscape playing through the theatre’s speakers, interlaced with moving light and shadow on the stage. As the piece itself began this was layered with live music performed by a team of musicians using their voices, drums, a guitar and various other instruments to create an invigoratingly live soundscape score for the dancers. There was a magical quality to the setting: a stage looking like the rippled stump of a giant tree with springy bamboo shoots growing randomly on its uneven surface and around the stage, in front of an audience seated on all four sides, was a path for the musicians, and occasionally for the dancers, to travel. Taken from the “Story of Amba,” a princess in the Sanskrit epic The Mahabharata, Until the Lions explores the unseen side of her story in an immensely fierce and passionate hour of choreography for three dancers (Akram Khan, Ching-Ying Chien and Joy Alpuerto RItter.

Until the Lions: Earlier in the festival on June 18, I had the chance to see Akram Khan’s dance production Until the Lions, and in this the music was even more integral. Long before the show itself began there was an almost subliminally present, ominous wind-like soundscape playing through the theatre’s speakers, interlaced with moving light and shadow on the stage. As the piece itself began this was layered with live music performed by a team of musicians using their voices, drums, a guitar and various other instruments to create an invigoratingly live soundscape score for the dancers. There was a magical quality to the setting: a stage looking like the rippled stump of a giant tree with springy bamboo shoots growing randomly on its uneven surface and around the stage, in front of an audience seated on all four sides, was a path for the musicians, and occasionally for the dancers, to travel. Taken from the “Story of Amba,” a princess in the Sanskrit epic The Mahabharata, Until the Lions explores the unseen side of her story in an immensely fierce and passionate hour of choreography for three dancers (Akram Khan, Ching-Ying Chien and Joy Alpuerto RItter.

Pss Pss: On the same day as Until the Lions I went earlier to see Pss Pss, a clown performance by the Italian Compagnia Baccalà at Luminato’s “Famous Spiegeltent,” not expecting it to connect at all with the later show and yet, much to my delight, it really did. Brilliant clown duo Camilla Pessi and Simone Fassari, looking like white face versions of Edward Everett Horton and a young Christina Ricci, began almost in silence, finding hilarity in the shared desire to eat an apple with barely a sound other than the whispered “pss pss” to catch one another’s attention. Then, the music erupted into the space – wonderfully circus-y dramatic music, selections from Ekberg, Torgue, Houppin and Lindvall – and these two goofy figures we were starting to love morphed into brilliant, slightly clumsy (but not really) acrobats throwing each other around. Pessi balanced on Fassari’s shoulders, head, even a single hand, the two bodies supporting each other then falling and tumbling and intertwining in a choreography that would find a serious counterpart in the passionate dance duets of Until the Lions later that day. Such synchronicity, and fascinating to see the relationship between two people depicted in such funny and then such searing detail.

Pss Pss: On the same day as Until the Lions I went earlier to see Pss Pss, a clown performance by the Italian Compagnia Baccalà at Luminato’s “Famous Spiegeltent,” not expecting it to connect at all with the later show and yet, much to my delight, it really did. Brilliant clown duo Camilla Pessi and Simone Fassari, looking like white face versions of Edward Everett Horton and a young Christina Ricci, began almost in silence, finding hilarity in the shared desire to eat an apple with barely a sound other than the whispered “pss pss” to catch one another’s attention. Then, the music erupted into the space – wonderfully circus-y dramatic music, selections from Ekberg, Torgue, Houppin and Lindvall – and these two goofy figures we were starting to love morphed into brilliant, slightly clumsy (but not really) acrobats throwing each other around. Pessi balanced on Fassari’s shoulders, head, even a single hand, the two bodies supporting each other then falling and tumbling and intertwining in a choreography that would find a serious counterpart in the passionate dance duets of Until the Lions later that day. Such synchronicity, and fascinating to see the relationship between two people depicted in such funny and then such searing detail.

All in all, an impressive array of shows at this year’s Luminato festival – and a reminder of how successful “music theatre” can be found in even the most unexpected of places.

The Luminato festival ran from June 14 to 25, in various locations throughout Toronto. For more information, visit www.luminatofestival.com.

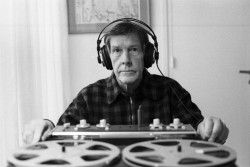

Toronto-based “lifelong theatre person” Jennifer (Jenny) Parr works as a director, fight director, stage manager and coach, and is equally crazy about movies and musicals.