It’s October — the new fall concert season’s in full swing! And, as with most season launches — 2011/12 being no different — there was a flurry of press releases sent ‘round toward the end of summer announcing new artistic appointments — those “new faces in old places.”

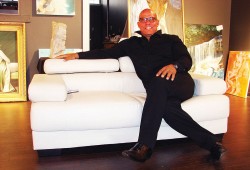

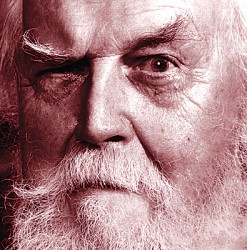

One such appointment is conductor Uri Mayer’s new role as artistic director and principal conductor with the Toronto Philharmonia Orchestra. Maestro Mayer, orchestral programme director and resident conductor of the Royal Conservatory’s Glenn Gould School, will lead the TPO in its upcoming concert series, at the George Weston Recital Hall.

One such appointment is conductor Uri Mayer’s new role as artistic director and principal conductor with the Toronto Philharmonia Orchestra. Maestro Mayer, orchestral programme director and resident conductor of the Royal Conservatory’s Glenn Gould School, will lead the TPO in its upcoming concert series, at the George Weston Recital Hall.

Last month, I had the pleasure of sitting down with Uri Mayer at the Royal Conservatory’s Koerner Hall café, where we chatted about his new appointment and related topics.

Right off the bat, I asked him what compelled him to take on the position with the TPO, given his busy schedule and his extraordinary conducting career to date.

"Actually, I’d known about the orchestra for some time. Last season they had a search for a new conductor/artistic director. I was not part of that [process] but I did conduct the first concert of the previous season. And I guess some people must have liked what I did. Because at the end of the season – really at the beginning of the summer – I was asked by the Board to take on the orchestra. And I thought about it, and I realized that it’s a very good group of musicians, in my neck of the woods, playing in a beautiful hall – at the Toronto Centre for the Arts – and I believed that my talents and my experience could bring them to the next level. And I was frankly flattered that they approached me.

"So this nice, relatively small ensemble, with a few concerts, I think can add a new dimension to musical life in North York, particularly, and in Toronto. And I’m delighted that I was asked to share my expertise and experience."

Click Here for the rest of the interview

And now to some other new appointees:

Judith Yan will make her debut on October 23, as the new conductor/artistic director of the Guelph Symphony Orchestra, in an all-Russian programme featuring works by Mussorgsky, Glazunov and Glinka, with guest violinist, Jacques Israelievitch (TSO concertmaster 1988–2008).

Speaking of Toronto Symphony Orchestra concertmasters, Jonathan Crow, the TSO’s newly appointed one, will be featured as soloist in two TSO programmes. On October 1 (at Roy Thomson Hall) and October 2 (at George Weston Recital Hall), Crow performs Beethoven’s Romance No.2 for Violin and Orchestra; as an added bonus, he’ll chat with TSO music director, Peter Oundjian, from the stage, following both performances. Also, pianist Emanuel Ax is performing Brahms’ Piano Concerto No.1 on the same bill. The second programme, on October 15 and 16, will feature Crow as soloist in a performance of Bach’s Concerto for Oboe and Violin and Brandenburg Concerto No.5, under the baton of TSO conductor laureate, Andrew Davis, at Roy Thomson Hall.

Unless you’re planning a trip to Saskatchewan in the near future, you won’t likely hear cellist Simon Fryer in his new appointment as principal cello with the Regina Symphony. However, if you’re in downtown Toronto on October 27, you’ll get to hear him perform Haydn and Weber trios with flutist Robert Aitken and pianist Walter Delahunt, and a new work for flute and cello by Chris Paul Harman, commissioned by the Women’s Musical Club of Toronto. The concert takes place at Walter Hall, and is a presentation of the WMCT’s long-standing, afternoon chamber series, of which Fryer is the artistic director.

Unless you’re planning a trip to Saskatchewan in the near future, you won’t likely hear cellist Simon Fryer in his new appointment as principal cello with the Regina Symphony. However, if you’re in downtown Toronto on October 27, you’ll get to hear him perform Haydn and Weber trios with flutist Robert Aitken and pianist Walter Delahunt, and a new work for flute and cello by Chris Paul Harman, commissioned by the Women’s Musical Club of Toronto. The concert takes place at Walter Hall, and is a presentation of the WMCT’s long-standing, afternoon chamber series, of which Fryer is the artistic director.

Leaving the world of shiny, new appointments for something a bit older, I would be remiss if, in closing, I did not provide at least a brief “Liszting” — I know. Ouch! — of some concerts marking the 200th anniversary of the birth of Franz Liszt (b. October 22, 1811):

• October 1, Kitchener-Waterloo Symphony, André LaPlante, piano, Centre in the Square, 101 Queen St. N., Kitchener;

• October 6, University of Toronto Faculty of Music, Jacqueline Mokrzewski, piano, MacMillan Theatre, 80 Queen’s Park;

• October 7, Gallery 345, Alejandro Vela, piano, 345 Sorauren Ave.;

• October 16, Royal Conservatory, Louis Lortie, piano, Koerner Hall, 273 Bloor St. W.;

• October 22, Christopher Burton, piano, Oriole York Mills United Church, 2609 Bayview Ave.; also performing November 6, Women’s Art Association of Canada, 23 Prince Arthur Ave.; and

• October 22, Lenard Whiting, tenor, Brett Kingsbury, piano, Christ Church Deer Park, 1570 Yonge St.

The rest of the full interview

In addition to his having guest conducted numerous leading Canadian and international orchestras, including the Montreal, Toronto and Houston symphonies, the Israel Philharmonic and with the National Ballet of Canada, Mayer has been principal conductor/artistic director of several orchestras and ensembles over the course of his career – Edmonton Symphony, Orchestra London (then known as the London Symphony), Israel Sinfonietta, Osaka’s Kansai Philharmonic Orchestra. As a result, he’s had his share of “first days” as “the new one.” So, I inquired as to how Mayer approaches those first days with a new orchestra, what he does to set the tone, the rapport.

"For me it’s about making music. And that’s universal. So whether I conduct in Toronto or, when I’ve conducted in Japan, Germany or Israel, I try to make music. And because it’s such a universal language, it’s fairly easy to do that. And then I try to convince people and inspire people to do it my way," he added, grinning.

"Now, when somebody has an artistic leadership role, then one looks at each day differently, because one has long-term goals to really improve the quality of playing, the quality in which the music is delivered. And one has an obligation to build the ensemble, the organization, to become better and better each day. So, one addresses more specific issues and makes gentle corrections as one progresses with the work/rehearsal process. And then one has to have an outlook of what the priorities are – particularly artistic priorities. What are the strengths and weaknesses of the ensemble? And then try to capitalize, initially, on the strengths but immediately build up the weaknesses. So, that when one performs on stage, the public gets a sense of commitment and fulfillment from the music that’s performed at the platform.

"So being the music director/artistic director of an orchestra is a commitment for some years, to improve whatever is there. They take the best and improve it. And take the weaker parts and improve them even more."

With that, I proceeded to ask Mayer what he considered to be a tough question to answer, which was, on average, how long it takes him to assess, and to “gel” with, a new orchestra.

"It’s a bit elusive. It takes many rehearsals and performances to gel. But, I think if one does music with sincerity, musicians get, immediately, the sense of where the soul of the person in front of them is, where their heart is, what their approach is. And that’s a little mystical because the baton doesn’t make any noise. And the hands, with the best technique, are relative."

During my research for this interview, I learned that on October 22, 2009, Mayer received an honourary doctorate in music from the University of Western Ontario and gave the fall commencement address, that same afternoon, to about 600 graduates, including those from the Don Wright Faculty of Music. (For those interested, his full, inspiring address is available on youtube at the following link: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uWNaJjhQPEs.)

In his address, he spoke of the medium of music crossing all boundaries of culture, language and economic status, and of communicating one’s vision, with the stroke of a baton, to a hundred musicians. After admitting having listened to his entire address, I wanted him to elaborate, further, on the mystery of communicating through music. With an easy laugh, he began:

"You know, the older I get, the more mysterious this becomes. I’ll tell you a story from my youth. When I was a young conducting student – all my student life I was double majoring in viola and conducting – I had the privilege of attending a masterclass given by a quite renowned conductor at the time, Antal Doráti, who was previous music director of the Detroit Symphony, Minneapolis, Philharmonia Hungarica, and he came to the University of Tel Aviv and gave this masterclass for a couple of conductors. And I stood up in front of my buddies, the students, and attempted to conduct the opening of Mozart’s Symphony No.35, “Haffner.” And I thought that technically I was quite good – very, very clear – but I could not get the orchestra to play together at all. I tried three, four times. And then the maestro, who was feeble and sort of aging, but mentally in good shape, stood up in front of them, and waved his arms; and really, there was no clarity in the motion, whatsoever. But the students, the orchestra, played fantastically together and in good spirit and it was an amazing tone, an ensemble, right off the bat. And I realized that, you know, conducting has nothing to do with clarity of the motion. It has to do with conviction. And it worked.

"So, ever since, I attempt to stand up in front of a group of people – with a lot of preparation – and whatever I like to do, play it with the best conviction that I have. And then the language does not matter.

"And, conductors are known to travel in different countries and often they do not speak the language of the host country. But they do marvelous music. And then they feel it; they can convey the feeling – with the eyes, with the body, with the soul."

I asked Mayer about some of his more memorable moments of achieving that mysterious simpatico or “kismet” with an orchestra.

"I had some beautiful moments like that, actually. Quite a few in different countries. One of them was years ago – Mahler Eighth [Symphony], in Taipei. Some concerts with the Montreal Symphony, of which I did quite a few. And some amazing concerts that people played for me in a radio orchestra in Hungary."

After Mayer mentioned Taipei, I thought about some of his other work in Asia and was curious about how he ended up conducting the Kansai Philharmonic Orchestra in Japan.

"A friend of mine heard that this orchestra was looking for a conductor and they recommended me to the orchestra. And I was asked to do a concert as a guest. And a few weeks after the concert, I got a call from the manager of the orchestra asking if I would like to become their next principal conductor. So, it was basically, very simple. How did their process work? I have no idea. But I spent many months there over a six and half, almost seven year period.

"And it’s interesting because the language was not easy. My Japanese is terrible; I learned a few words. So I worked mostly in English and in German. A lot of the people in Japan were trained in Germany or had German training. So [German] terminology is very familiar to them. And really, during rehearsals I tried to speak very little and do as much conducting as possible and work on the essentials. And they were fantastically prepared, I must say, in attitude and seriousness."

I asked about the size of the orchestra and Mayer said it was a good size of about 80 to 85 musicians, adding that they played big repertoire with an absolutely full complement. And he continued:

"The number of full scores that people brought to the rehearsals was stunning for me; I’d say 30 to 40% of the orchestra members brought scores. So they knew the repertoire and they knew what else was going on. It was beyond anything I’d seen anywhere or experienced with other orchestras – and some very good orchestras, by the way."

Mayer was with Kansai from 1994 to 2000. And from 2005 to now, he has been involved with the Royal Conservatory, initially on a part-time basis, with the level of involvement increasing two years ago, when he became director of the orchestral programme and resident conductor of the Royal Conservatory’s Glenn Gould School. So I asked him what he was up to between 2000 and 2005.

"Guest conducting in different countries. Also, I did quite a few performances with the National Ballet of Canada. So, from the mid–1990s I did quite a few productions with the National Ballet which was a major time commitment and a wonderful opportunity to learn the art of the ballet, or some of the art of the ballet."

I couldn’t resist asking if he had a favourite ballet. His answer? Nutcracker. Of course, I had to ask him why?

"Because I think the music is so gorgeous. And I’ve conducted many performances of that ballet but each time the music is lovelier and lovelier. Some people will probably think that this is silly, because it’s overplayed. But I think Tchaikovsky was a genius.

"And music is music, regardless of whether it’s played on stage or in the pit. Good music is good music."

Given the number of times he has conducted Nutcracker over the years, I wondered about how he managed then, and manages now, with other “overplayed” repertoire, to avoid a dullness and to keep things fresh.

"I approach each performance as a new experience. But if you don’t love it, you don’t do it, or you mustn’t do it. Serious musicians, I think, will agree that when one approaches all scores – I mean, each time one goes back to the score, whether it’s Tchaikovsky or Mozart or Bach or something newer, but when one studies a score in depth – each time one discovers a new element, a new angle, a new beauty. And it’s such joy to look at this thing and say, How? What did he or she mean? How come? How did they have the wisdom and the inspiration to do that? And I marvel at the gifts of composers who could put down on paper – today, maybe on computer [he laughs] – such gorgeous stuff, and such complex scoring, ideas, sonorities.

"We’re [the Royal Conservatory Orchestra] working now on Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition, Ravel orchestration. It’s a score I’ve conducted, probably in two dozen countries for different occasions. And I’m studying the score again, and my god, you know, it’s like discovering a new piece. How smart, how brilliant, how many colours can somebody like Ravel add to Mussorgsky’s excellent piece!

"I never had aspirations to compose. Since I was a child, my leaning and attraction was to perform. And hence, when I study scores, and the more I get into it, the more I need to learn. And to be able to discover new stuff – new stuff to me – seeing the notes in a new light, or under a new light, or a new shade; trying to understand the emotions, or the possible ways to interpret it, is so gratifying.

"And then, one never has enough time – nor should one explain everything in the rehearsal process, (either to the orchestra or the public) – but, I think if one understands the score and goes into depth, then one hopefully can convey, often without words, the meaning and the depths of emotions that go into that."

Speaking of repertoire and newness and freshness, I turned the focus back to Mayer’s new appointment with the Toronto Philharmonia, and asked him about what he envisioned for the orchestra and the type of repertoire he would like to work on with the TPO.

"I envision them playing mostly classical, romantic repertoire, and added to that, some Canadian, some American stuff – a touch, a taste of the modern. But the foundations of the programmes will be rather traditional. The orchestra doesn’t have enough concerts to cover all the range, all the possible range. And it needs, I think, in building and improving the quality of the orchestra, classics. And Mozart and Beethoven are the best. So, I think it will be highly traditional.

"There’s a core of about 40 musicians who play regularly with the orchestra. So, the size and the budget do not lend themselves to playing the huge, romantic, and big, big repertoire. There’s a wonderful orchestra in the city that plays that. It’s called the Toronto Symphony [he laughs]. And I believe that they do a wonderful job with that and the Toronto Philharmonia does not, and must not attempt to go into that [repertoire].

"But, the other repertoire that we’ll play a lot – and I’m going to choose it carefully – will be fitting for the size of the orchestra, and will also appeal to their loyal public and their base. There’s a base on which we have to build, and we have to please that. But we are going to make an appeal to people who love classical music and who love coming to the Toronto Centre for the Arts. And hopefully, eventually, I’ll take them out from there into other communities."

I then asked if he would share with me what the TPO will be performing on January 25, for its opening concert of the season.

"Yes. Actually, it’s quite close to Mozart’s birthday, so it’s going to be an all-Mozart programme: Serenata Notturna, a “little known” piano concerto, Mozart K467 in C Major, also known as the “Elvira Madigan” [he laughs] (because of the movie), and Symphony No.40 in G Minor, the 'Great G Minor.'"

When I said it sounded like a nice program, he replied, with a smile, “I think it’s good Mozart. There are probably a dozen 'great composers.' And certainly Mozart belongs there. But, the orchestra has a tradition of, in January, celebrating Mozart’s birthday with an all-Mozart programme.”

And when I asked if the TPO usually starts off its season in January, Mayer explained that this was a unique situation, because of the search and the transition year which the orchestra had. He said that the TPO had decided, prior to his coming on board, that they would concentrate their efforts on 2012 and have concerts, once a month, starting in January, adding that the TPO’s season usually runs from October to April.

I then wondered whether, aside from having conducted them last year, he’d met with the orchestra since the new appointment and his answer was “no.” And the first rehearsal?

That’s going to be in January – January 23 or 24. When Mayer told me that, I commented on how amazing it is that conductors typically spend such little time together with an orchestra, in rehearsal, before a performance, acknowledging, of course, the hundreds of hours that go into the prep time, prior to meeting. His unequivocal reply:

"Look, we’re all professionals, starting with the musicians. These people are highly qualified, very well-prepared, very dedicated, very devoted. When I conducted them in October last year, in an all-Beethoven programme, with relatively short rehearsal time, people were very well-prepared. This is world-wide. Very few orchestras have long rehearsal periods. Musicians are serious about the profession and they come knowledgeable. Even those who don’t bring the scores know the repertoire [he grins]. Unlike dance or opera, where the rehearsal period has to be longer, symphony programmes are put together in a relatively short time at a very high level. So a lot of the preparation is in the background. And that’s the way it works."

As we began to wind down the interview, I asked Mayer about what he thought the future might hold for him in terms of any other “new posts” or artistic challenges down the road. Here’s what he told me:

"I enjoy every day as it comes. Right now, I’d like to put this orchestra on the map, as a force, an additional symphony orchestra in the city, to complement what’s already here, and to attract the public, particularly North York, to their concerts. And I’m convinced that we’ll play at a level – high enough and satisfying – that we’ll attract a lot of people.

"This is a huge city. There are a lot of music lovers in this city. There’s room on the stages; there are several very good concert halls. And there’s a public north of Eglinton, and certainly north of the 401, that likes the [George Weston Recital] hall – it’s a magnificent hall. So, we are going to show what we can do and hopefully people will listen to us."

And finally, in his 2009 address to those 600 graduates of the University of Western Ontario, Mayer spoke of those who mentored, assisted and influenced him along the way – great musicians and conductors such as Odeon Partos, Shalom Riklis, Walter Trampler, Leonard Bernstein, Charles Dutoit, to name a few. So my last question to Maestro Mayer was about whether mentoring others now played an important role in his professional life.

"Absolutely! I do that on a regular basis. Whether it’s with young instrumentalists who come and play for me or young aspiring conductors who chat with me about scores, discuss scores, and who have come to my rehearsals. There are several people like that [in my life]. And I think it’s critical that I share my experiences and my insight into the music and into the scores that I have. It’s for them to take this from me and something else from somebody else.

"I was extremely lucky to be influenced by some magical people who were very generous with their time and very helpful in guiding me. Because of them, I am what I am. And I will be always indebted to them for the warmth and the wisdom that they gave me. So, if somebody comes to me, and asks questions or advice – someone who needs help – I am more than delighted to help. I feel it’s a privilege and an obligation. And I do it with all my heart and commitment. And if I can help one person improve, or find their goals or get closer to their goals and aspirations, that’s my goal."

It was a pleasure to chat with Uri Mayer. He was kind, candid, good-humoured and generous with his time. And it was clear that he loves doing what he does. It was also clear that he is well-liked around the Royal Conservatory. Many people strolled by our table, they all smiled at Mayer, and they all said “hello”; and he said “hello” back. Consequently, the interview tape was peppered with hellos, throughout. A fitting note on which to end.

One last reminder: You’ll be able to catch Uri Mayer in action, with the TPO, January 25, at the Toronto Centre for the Arts’ George Weston Recital Hall.

Enjoy this new and exciting season!

Sharna Searle trained as a musician and lawyer, practised a lot more piano than law and is listings editor at The WholeNote. She can be contacted at classicalbeyond@thewholenote.com.

Arraymusic’s October 14 foray into Gallery 345 also provides a neat segue into New Music Concerts’ next big event. It was Arraymusic artistic director and gifted percussionist Rick Sacks who persuaded NMC’s Robert Aitken to take on the challenge of presenting Charles Wuorinen’s “Percussion Symphony for 24 Players,” the work that anchors NMC’s upcoming October 30 concert at the Betty Oliphant Theatre. The work includes two pianos and a celesta (think Sugar Plum Fairy) and an entire platoon of top-flight percussionists, so it’s not that often performed. Rarely enough, in fact that Charles Wuorinen himself is coming to town to direct. (He will, as others before him, be astonished by the depth of musical talent in this town.) If you are going, get there 45 minutes ahead for Aitken’s “Illuminating Introduction.” Aitken is as deeply into the music as his interviewees and it makes for fascinating listening. There’s also a new piece by Eric Morin on the programme, matching Joseph Petric on accordion with the Penderecki String Quartet — that’s three accordionists in two concerts this season already for NMC! And those of you who also take in the Women’s Musical Club concert on October 16 will have an all too rare opportunity — the chance to hear a new work (Chris Paul Harman’s Duo for flute and cello) performed twice in four days!

Arraymusic’s October 14 foray into Gallery 345 also provides a neat segue into New Music Concerts’ next big event. It was Arraymusic artistic director and gifted percussionist Rick Sacks who persuaded NMC’s Robert Aitken to take on the challenge of presenting Charles Wuorinen’s “Percussion Symphony for 24 Players,” the work that anchors NMC’s upcoming October 30 concert at the Betty Oliphant Theatre. The work includes two pianos and a celesta (think Sugar Plum Fairy) and an entire platoon of top-flight percussionists, so it’s not that often performed. Rarely enough, in fact that Charles Wuorinen himself is coming to town to direct. (He will, as others before him, be astonished by the depth of musical talent in this town.) If you are going, get there 45 minutes ahead for Aitken’s “Illuminating Introduction.” Aitken is as deeply into the music as his interviewees and it makes for fascinating listening. There’s also a new piece by Eric Morin on the programme, matching Joseph Petric on accordion with the Penderecki String Quartet — that’s three accordionists in two concerts this season already for NMC! And those of you who also take in the Women’s Musical Club concert on October 16 will have an all too rare opportunity — the chance to hear a new work (Chris Paul Harman’s Duo for flute and cello) performed twice in four days! Speaking of Koerner Hall, Alex Pauk’s Esprit Orchestra was the first of the core new music presenters to move its whole season to Koerner. Having an extra 400 seats to sell was a daunting challenge, but with curiosity about the new hall high last season it was a good time to take the plunge. After all, without extra seats how do you take on the challenge of outreach? This year they are taking it a step further, switching from a Sunday night format to include three week nights, making reaching out to a school audience viable.

Speaking of Koerner Hall, Alex Pauk’s Esprit Orchestra was the first of the core new music presenters to move its whole season to Koerner. Having an extra 400 seats to sell was a daunting challenge, but with curiosity about the new hall high last season it was a good time to take the plunge. After all, without extra seats how do you take on the challenge of outreach? This year they are taking it a step further, switching from a Sunday night format to include three week nights, making reaching out to a school audience viable.