Surveying the first group of concerts out of the gate this fall, I notice that three of them have a royal theme.

Surveying the first group of concerts out of the gate this fall, I notice that three of them have a royal theme.

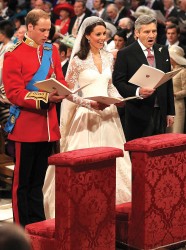

Considering the degree to which Western choral music is intertwined with the history of European royalty, this kind of theme might be considered obvious, even uninventive. But the degree to which pretty much the entire world raptly followed the latest House of Windsor wedding last April (followed by the new couple’s tour of Canada) gives these concerts an added resonance. It makes us enjoy anew not only the thoroughly inventive music of the master composers that found employment at royal courts, but raises questions as to what the meaning of royalty is at the beginning of a new century.

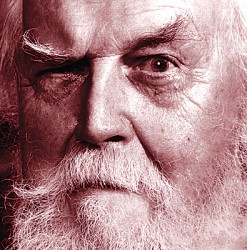

For some, the very existence of a British royal family is worse than an anachronism in a democratic world — it is an insult to the idea of human equality, a desecration to the memory of the legions of innocent people that perished over the centuries through royal exploitation, neglect, intrigue and war. To others, it is a fun diversion, well worth the generous stipend paid to the royal family. Canadian writer Robertson Davies saw modern royalty in archetypical terms — a connection to a collective past that combines historical reality with myth and legend.

What does this mean in terms of music? The English royal court was a fecund ground for composers and performers well into the 18th century. The resurgence that began with Elgar and culminated with Britten continues strongly with the work of Tavener. A strong argument can also be made against the received wisdom that British music died in the 19th century; modern church musicians continue to find value in the choral works of Parry and Stanford.

On September 16 Kevin Mallon’s Aradia Ensemble will perform “Music of the English Chapels Royal,” with verse anthems by Locke, Humfrey and Purcell, among others. Verse anthems are a particular sub-species of choral composition in which full choruses alternate with solo passages. English composers of the Reformation found both contemplative and dramatic elements inherent in this form and the challenge for choirs is to execute them in a manner which avoids the monochromatic sound that is the bane of church music performance.

The Cantemus Singers is a relatively new Toronto choir, conducted by Michael Erdman. They specialize in secular music of the Renaissance, though for their “Rule Britannia” concert on September 24 and 25 they will be performing sacred works by Taverner and Gibbons as well as secular music by familiar Elizabethan composers. They will also be performing rounds by Purcell, fun and rowdy works that are most enjoyable in a live setting.

From September 21 to 25, Tafelmusik Baroque Orchestra and Chamber Choir perform “Music Fit for a King.” This concert takes a pan-national approach to regality, showcasing music that was part of the French court of Louis XIV and the Viennese court of Emperor Leopold I, as well as the music of Purcell and that of Frederick the Great, who wrote at a time when we prized royalty for their artistic talent rather than their polo skills or their shapeliness in a bikini.

One historical source reports that Frederick the Great received a standing ovation from the audience every time a composition of his was performed. This seems entirely plausible to me. What critic would dare risk royal censure by remaining seated? Still, the source in which I found this information is a comic book published in the 1970s, so I can’t vouch for its accuracy with complete certainty.

As the makeup of Canadian society changes and our connection to our British Commonwealth past becomes increasingly remote, will we see less of concerts with a royal theme? In the meantime, what explains our ongoing fascination with the recent royal marriage? Was it simply part of our People Magazine-fueled general preoccupation with those we consider rare and glamorous? Or, watching the union of what may be our future king and queen, did we enact a connection with our ancestors — peasants, for the vast majority of us — that approached something primal and ancient?

Let the last word in this first column of autumn 2011 belong to the Canadian writer mentioned above who was by no means uncritical of either royalty or privilege, but who also had a keen eye for the hypocrisy that can underpin even the best of modern egalitarian intentions. In High Spirits, his wonderful, humorous collection of ghost stories, Robertson Davies describes a meeting between himself and the spirit of one of the current English queen’s most illustrious ancestors:

Let the last word in this first column of autumn 2011 belong to the Canadian writer mentioned above who was by no means uncritical of either royalty or privilege, but who also had a keen eye for the hypocrisy that can underpin even the best of modern egalitarian intentions. In High Spirits, his wonderful, humorous collection of ghost stories, Robertson Davies describes a meeting between himself and the spirit of one of the current English queen’s most illustrious ancestors:

“I am a democrat. All my family have been persons of peasant origin, who have wrung a meagre sufficiency from a harsh world by the labour of their hands. I acknowledge no one my superior on grounds of a more fortunate destiny, a favoured birth. I did what any such man would do when confronted by Queen Victoria; I fell immediately to my knees.”

Ben Stein is a Toronto tenor and theorbist. He can be contacted at choralscene@thewholenote.com.