Transformative Meetings: Avital and Yang

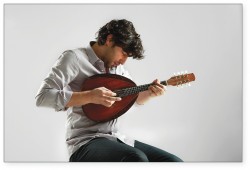

Avi Avital: Israeli-born mandolin virtuoso Avi Avital (b. 1978) – who will appear at Koerner Hall with the zestful Dover Quartet on February 11 – once described his relationship with his instrument as “a bit like a rider and his horse.”

Avi Avital: Israeli-born mandolin virtuoso Avi Avital (b. 1978) – who will appear at Koerner Hall with the zestful Dover Quartet on February 11 – once described his relationship with his instrument as “a bit like a rider and his horse.”

“I know my mandolin very well,” he told 15questions.net. “My hands remember blindly every curve and every fret of it. I have a deep understanding of how it works, but when I’m on stage it becomes part of me – I almost forget I’m holding it.”

A relative of the lute, the mandolin has grown in popularity over the last 300 years. “Familiar and foreign, folkish and classical, the mandolin is both a musical chameleon and a seasoned traveller,” Avital wrote in his introduction to his eclectic Deutsche Grammophon CD Between Worlds (2014).

Avital told Fifteen Questions about a transformative meeting he had in his mid-20s with the famed klezmer clarinetist Giora Feldman. After Avital played him a piece by Bloch, Feldman asked him to improvise. When Avital said he didn’t know how, Feldman insisted. “So I closed my eyes and for the first time in my life I started to play something that wasn’t written in notes. Giora took his clarinet and joined me, and we continued to improvise together for a little while that afternoon. That encounter opened the window to a new world and led me to play different genres of music.”

Avital spoke with medici.tv last year about his admiration for Menuhin, Heifetz and Rubinstein, about how he takes different things from different artists. And about how he was “really into rock ‘n’ roll” when he was 14. “I was the real grunger from Seattle; I remember making a lot of noise on the drums.”

He still carries something of the rock band experience when he plays in a classical music hall.

Describing his arrangement of Bach’s Chaconne from the Partita No.2 for solo violin, he talked about how the freshness for an audience of discovering a monumental piece of music played on a different instrument is like hearing it for the first time. And that you hear contemporary music differently after listening to Bach in a recital. “It’s like the ginger with the sushi or the lemon sorbet between the dishes in a very fancy restaurant.”

So on February 11, after he plays the Chaconne, he and the Dovers will perform the Canadian premiere of David Bruce’s Cymbeline, for string quartet and mandolin, a piece written for him in 2013 and dedicated to Avital and his wife “in honour of their recent marriage.” The title is an old Celtic word meaning Lord of the Sun. “I think the idea of the piece being about the sun emerged out of the colours of the string quartet and the mandolin together,” Bruce wrote on his website. “The mandolin itself has always seemed to me to create a ‘golden’ sound, and when combined with the warmth of the strings it seems now obvious that I should be drawn towards something warm and golden.”

The concert opens with Tsintsadze’s Six Miniatures for String Quartet and Mandolin; Tsintsadze, who died in 1991, invariably wove his Georgian homeland’s folk music into his works. Then the Dovers give Avital a break when they take on Smetana’s penetrating autobiographical tone picture, his String Quartet No. 1 in E Minor “From My Life.” I’ve been eagerly awaiting their return to town ever since their memorable Toronto Summer Music performance of Beethoven quartets last summer. The Dovers’ playing was empathetic, subtle, impeccably phrased, marked by forward motion, drive and energy, musically mature, vibrant and uncannily unified in purpose and execution. Their collaboration with the larger-than-life Avital promises much joyous music making.

In Mo Yang was 19 when he became the youngest winner of the Paganini International Violin Competition in 2015. Now 21, he makes his Canadian recital debut March 5 (with pianist Renana Gutman) presented by Mooredale Concerts. Born in Indonesia, Yang moved to Korea at two and began playing violin at five. He currently studies with Miriam Fried on a scholarship to the New England Conservatory. Yang told me in an email exchange that he first met Fried in Korea when he was about 14 and played the Mendelssohn concerto for her. “I was struck by how drastically my sound improved with her methods of sound production.” In 2012, when it was time to find his next teacher, he wanted to have another lesson with her. “She was about to come to Korea to attend a festival in Seoul. I went to her hotel room and played the Tchaikovsky concerto. I was again struck and determined that she had to be my teacher.”

In Mo Yang was 19 when he became the youngest winner of the Paganini International Violin Competition in 2015. Now 21, he makes his Canadian recital debut March 5 (with pianist Renana Gutman) presented by Mooredale Concerts. Born in Indonesia, Yang moved to Korea at two and began playing violin at five. He currently studies with Miriam Fried on a scholarship to the New England Conservatory. Yang told me in an email exchange that he first met Fried in Korea when he was about 14 and played the Mendelssohn concerto for her. “I was struck by how drastically my sound improved with her methods of sound production.” In 2012, when it was time to find his next teacher, he wanted to have another lesson with her. “She was about to come to Korea to attend a festival in Seoul. I went to her hotel room and played the Tchaikovsky concerto. I was again struck and determined that she had to be my teacher.”

It’s striking as well that Yang’s Paganini success came 47 years after Fried herself won the same competition. I asked if she had passed on any insights to him. “She told me her story of winning the competition and encouraged me [saying] that I had a good chance of winning. During the competition, I was dissatisfied with one of the rehearsals and frustrated. I called her and she told me how to deal with the situation, which relieved me. It was also very insightful of her to recommend that I eat pesto.”

Yang’s Toronto program begins with Bach’s unaccompanied Violin Sonata No.1 in G Minor BWV 1001. Bach has only recently been included in his recital programs. “Bach’s music is endlessly imaginative and has such communicative power,” he said. “I would like to share this with the audience, not just with jurors [because these pieces are always required repertoire at auditions and competitions].”

He loves the rhapsodic aspect of Ysaÿe’s music and thinks the Sonata No.3 in D Minor for Solo Violin Op.27 No.3 “Ballade” highlights that rhapsodic aspect more than any of the other sonatas. “Despite its obscurity, the beauty of Schumann’s Violin Sonata No.3 in A minor is evident throughout,” he told me. “I want to show that this is not a piece by a madman but a person who has extraordinary imagination and introspection.” Beethoven’s Violin Sonata No.7 in C Minor Op.30 No.2 is new for him; he started learning it only a month ago. ”I am especially working on the overall architecture of the sonata, because it is understanding the structure and living through the whole piece with a sense of inevitability that heighten the incredible drama of the piece,” he said.

His answer to my question about what musicians may have influenced him surprised me: “I am more influenced by non-musicians,” he said. “Plato’s Theory of Forms greatly inspired me; the idea that the most accurate reality exists in a non-physical world, and what we sense is a mere reflection of Idea, made me rethink the relation between composer, composition and performer. The audience is often an influential figure in my musical career; I got to play in a senior centre once and the smile of five patients who listened to me taught me an important lesson about the societal role of a musician.”

That’s quite a revealing comment, especially from a musician launching an international career. He’s clearly a talent to watch. When he made his Carnegie Hall recital debut in April 2016 he wanted to play on a great instrument. With the help of Reuning & Sons Violins, he met the owner of a Stradivarius violin and was very fortunate to be given a loan of it. As Anthony Tommasini wrote in the New York Times of that Carnegie concert, “Mr. Yang proved himself most deserving of this fine instrument in an impressive program.”

Music Toronto. Music Toronto’s 45th season continues at the Jane Mallett Theatre with a pair of “discovery” concerts (pianist Ilya Poletaev on February 7 and the Eybler Quartet on February 16) before welcoming back the Prazak Quartet on March 2.

Poletaev began studying piano in Moscow at six, continuing his lessons in Israel before emigrating to Canada at 14. A year after winning the 17th JS Bach competition in Leipzig, he joined the Schulich School faculty at McGill. His February 7 recital at the Jane Mallett Theatre includes Bach’s richly textured French Overture BWV831, Enescu’s hymn to his native Romania, the Sonata in F-sharp Minor Op.24 No.1 and Schumann’s episodic Humoreske Op.20.

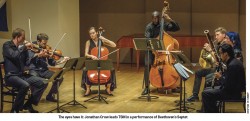

The Eybler Quartet consists of cellist Margaret Gay and three members of Tafelmusik (violinists Julia Wedman and Aisslinn Nosky, and violist Patrick G. Jordan), two of whom (Wedman and Aisslinn) are also members of I FURIOSI. Devoted to the repertoire of the early years of the string quartet, their namesake is the little-known composer Joseph Leopold Edler von Eybler, a contemporary of Mozart who outlived Schubert. True to form, their February 16 program includes works by the lesser-known Viennese-based Johann Baptist Vanal and Franz Asplmayr as well as Haydn’s Op.33 No.1 (the first of his quartets “composed in a new, special way”) and Beethoven’s gentle Op.18 No.3.

In 2015, Jana Vonášková, a graduate of the Royal College of Music in London and a member of the Smetana Trio for nine years, joined the Prazak Quartet as first violinist, succeeding Pavel Hula who founded the quartet in 1972. Second violinist Vlastimil Holek has been with the Prazak for nearly four decades. Violist Josef Kluson is the last founding member still active in the quartet. Cellist Michal Kanka joined the group in 1986. Internationally acclaimed and an audience favourite, the Prazak makes their seventh appearance on the Jane Mallett stage since 1993 with a March 2 program that begins with late Haydn (the buoyant Op.71 No.1) and Bruckner’s rarely performed, highly Romantic Quartet before concluding with Dvořák’s beloved “American” Quartet.

TSO. The Toronto Symphony welcomes the renowned Jiří Bělohlávek, music director and artistic director of the Czech Philharmonic, to lead the orchestra in Martinů’s Symphony No.6 “Fantaisies symphoniques.” Bělohlávek has been focused on Martinů’s work for years so this is an opportunity to hear what may be a definitive reading of the piece. Adding to the allure of these February 9 and 11 concerts is the imposing figure of Garrick Ohlsson, the soloist in Beethoven’s resplendent Piano Concerto No.5 “Emperor.” Debussy’s seductive Première Rhapsodie, which opens the program, is a showpiece for TSO principal clarinetist Joaquin Valdepeñas’ sweet sound. On February 15 and 16, rising star Jakub Hrůša, a Czech conductor half Bělohlávek’s age who is permanent guest conductor of the Czech Philharmonic, leads the TSO in two masterful orchestral ruminations, Richard Strauss’ Death and Transfiguration and Scriabin’s The Poem of Ecstasy. That being said, the main attraction on the program will be Schumann’s Piano Concerto with soloist Jan Lisiecki, the first time Toronto audiences will hear what is the major work on Lisiecki’s latest CD. Another treat on the TSO menu: February 18, American conductor Sarah Hicks will lead the TSO in two performances providing a live accompaniment to the Pixar animated classic Ratatouille. This delightful, sophisticated film about an enterprising rat who creates his inimitable ratatouille dish in a Paris restaurant for a discerning food critic, features a sentimental symphonic score that is all cane sugar, no saccharine. Peter O’Toole’s melodious narration as the critic adds another musical layer to the proceedings.

RCM. In addition to the Avital-Dover recital, the Royal Conservatory is presenting three other concerts of note. On February 4, Gidon Kremer and Kremerata Baltica celebrate Kremer’s 70th birthday year and the ensemble’s 20th at Koerner Hall with “Russia – Masks and Faces,” including music by Pärt, Weinberg, Tchaikovsky, Silvestrov and Mussorgsky (an arrangement for string orchestra of the iconic Pictures at an Exhibition). A free concert (ticket required) February 5 in Mazzoleni Concert Hall will introduce Andrés Díaz, the inaugural Alexandra Koerner Yeo Chair in Cello at the RCM. Díaz performs works by Martinů, Richard Strauss and Pulitzer Prize-winning composer Kevin Puts, with Barry Shiffman and other special guests. Then on March 3 acclaimed Scottish-born violinist Nicola Benedetti and the Venice Baroque Orchestra celebrate the pleasures of her Italian heritage with an engrossing program of selections by Galuppi, Avison (after Scarlatti), Geminiani and two works by Vivaldi including The Four Seasons. Finally, the masterful Sir András Schiff brings his classical warmth to a selection of late-Schubert piano pieces March 5. The composer’s Moments musicaux D780 and Drei Klavierstücke D946 are bookended by his two sets of Impromptus D899 and D935, delightful works that are made for Schiff’s own stylish sense of panache.

QUICK PICKS

Feb 7: Following his refreshing performance of Mozart’s Rondo for Violin and Orchestra K373 with the TSO (part of this year’s Mozart @261 festival), 19-year-old Kerson Leong (and collaborative pianist Philip Chiu) gives a free noontime recital of French music at the Richard Bradshaw Amphitheatre.

Feb 13: Associates of the Toronto Symphony adopt a French accent for a program of Poulenc’s insouciant Sonata for Flute and Piano, Stravinsky’s cunning Suite from L’Histoire du soldat and TSO bassoonist Fraser Jackson’s arrangement of Ravel’s jazzy Piano Concerto in G. Mar 6: TSO second oboist Sarah Lewis is featured in Mozart’s charming Oboe Quartet in F K370 and Britten’s bewitching Phantasy Quartet for Oboe and Strings Op.2.

Feb 13: The Perimeter Institute, one of the joys of Waterloo, presents the remarkable violinist Christian Tetzlaff and the outstanding pianist Lars Vogt in a compelling program of Beethoven, Mozart, Widmann and Schubert.

Feb 19: Any chance to hear Jan Lisiecki is a chance to be taken. In this Isabel Bader Centre for the Performing Arts’ recital in Kingston, the super-talented young pianist treats us to repertoire new to Southern Ontario: Bach’s Partita No.3 in A Minor BWV827; Schumann’s Klavierstücke Op.32; Schubert Impromptus Op.142; and a trio of Chopin pieces including the high-powered Scherzo No.1 Op.20.

Feb 21: Sae Yoon Chon, a Korean-born scholarship student at GGS and a prizewinner at the last two Hilton Head International Piano Competition tackles Beethoven’s monumental Sonata No.29 in B-flat Op.106 “Hammerklavier” in a COC free noontime concert at the Richard Bradshaw Amphitheatre. (Mar 7: Fellow GGS scholarship student, Unionville-born Charissa Vandikas, performs works by Chopin, Schumann and Rachmaninoff in her own COC free noontime concert.)

Feb 23: Irène Jacob performs original material sprinkled with covers of Georges Brassens at Jazz Bistro. The French actress, luminous in Krzysztof Kieślowski’s Double Life of Veronique (where she sang) and Three Colours: Red, recorded her first album Je Sais Nager (I Know How To Swim) in 2011 with her brother Francis, a guitarist and jazz-based arranger. Now they’re touring their latest CD, En Bas de Chez Moi (Downstairs at My House), with their multinational band (including Senegalese bassist Mamadou Ba and Franco-Peruvian Jose Ballumbrosio).

Feb 26: The Kitchener-Waterloo Chamber Music Society presents the Turgeon Piano Duo, husband-and-wife pianists, in a surefire program: Dvořák’s Slavonic Dances, Mozart’s Sonata in C K521, Gavrilin’s Sketches, Ravel’s Mother Goose Suite and Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue. Mar 5: Israel’s Aviv String Quartet begins a traversal of Mozart’s last ten string quartets in three concerts in five days at the KWCMS Music Room.

Mar 4: The astonishingly gifted 23-year-old Montreal native Stéphane Tétreault, brings his Bernard Greenhouse cello to the Toronto Centre for the Arts when he performs Saint-Saëns’ Cello Concerto No.1 with Sinfonia Toronto. Conductor Nurhan Arman also leads the orchestra in Morawetz’s Sinfonietta and Arman’s own string orchestra arrangement of Grieg’s String Quartet in G Minor.

Mar 5: The famed Boston Symphony Orchestra (with special guest Emanuel Ax performing Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No.2) makes their first visit to Canada in 21 years. Conductor Andris Nelsons also leads the orchestra in Berlioz’s delirious, spectacular and enduring Symphonie Fantastique. Look for my interview with BSO principal horn James Sommerville elsewhere in this issue.

Paul Ennis is the managing editor of The WholeNote.