![]()

My musical life in Toronto this summer was bound up in Toronto Summer Music’s “London Calling” season, 25 days of activities spurred by the idea of musical life in London throughout the centuries. That clever conceit enabled the program to broaden its content beyond English works to encompass music heard in London, particularly in the popular 19th-century concert-giving associations. TSM’s 11th edition, the sixth and final under its personable artistic director Douglas McNabney, was its most extensive to date, unfurling a huge amount of repertoire between July 14 and August 7. I was able to take in ten concerts, three masterclasses and a rehearsal, making for many memorable moments, much of which I have already written about on thewholenote.com. Here are some highlights:

My musical life in Toronto this summer was bound up in Toronto Summer Music’s “London Calling” season, 25 days of activities spurred by the idea of musical life in London throughout the centuries. That clever conceit enabled the program to broaden its content beyond English works to encompass music heard in London, particularly in the popular 19th-century concert-giving associations. TSM’s 11th edition, the sixth and final under its personable artistic director Douglas McNabney, was its most extensive to date, unfurling a huge amount of repertoire between July 14 and August 7. I was able to take in ten concerts, three masterclasses and a rehearsal, making for many memorable moments, much of which I have already written about on thewholenote.com. Here are some highlights:

McNabney’s farewell season got off to an impressive start with a concert of English music for strings conducted by Joseph Swensen. He introduced the evening and noted that Britten’s Serenade for Tenor, Horn and Strings, which we were about to hear, was the first piece he wanted to program in the festival. The remarkable performance which followed - by American tenor Nicholas Phan, TSO principal horn Neil Deland and the TSM Festival Strings - was breathtaking in its execution. Deland’s horn playing was unforgettable for its purity of tone, a wondrous support for the mercurial tenor and the assorted poetic anthology, the text taken from some of Britten’s favourite verse by the likes of Tennyson, Blake and Keats; the powerful Blow, Bugle Blow, the foreboding horn of The Sick Rose, the anguished and awestruck Lyke Wake Dirge and the seductive voice of To Sleep. What a rare treat!

In a refreshing concert July 19, pianist Pedja Muzijevic’s presented “Haydn Dialogues,” a 75-minute performance of four Haydn sonatas separated by pieces by Oliver Knussen, John Cage and Jonathan Berger. Passionate about mixing old and new music, Muzijevic is also a genial talker, combining a delicious wit and the occasional catty comment with a streamlined historical sensibility that made it easy to relate to Haydn and his relationship with his patrons, the Esterházy family, and to the timely invitation by the British impresario, Salomon, to live and work in London. (“Talk about London Calling,” Muzijevic added in a clever aside.)

The Coronation of King George II took place in October of 1727; Handel was commissioned to write four anthems for the ceremony. On July 26 in Walter Hall, Daniel Taylor led his Theatre of Early Music in a delightful hour-long re-imagining of the event that literally and figuratively was the grand centrepiece of TSM’s season. In addition to using music of the day, Taylor had the wisdom to include three anachronistic elements: Hubert Parry’s I Was Glad and Jerusalem, as well as John Tavener’s Hymn to the Mother of God, which broadened the evening and extended the ceremonial maelstrom into the 20th century. The effervescent Taylor and his company had the musical smarts to carry it off.

A week of exceptional musicality (which also included TSO concertmaster and TSM artistic director designate, Jonathan Crow, headlining an enjoyable evening of mostly British chamber music, July 28) concluded July 29, with an outstanding recital by the talented Dover Quartet. It was TSM’s nod to the Beethoven Quartet Society of 1845, the first public cycle of the composer’s complete string quartets, a series of London concerts each of which included an early, middle and late quartet. So, in that spirit, the capacity Walter Hall audience was treated to Op.18 No.4, Op.59 No.3 and Op.132.

The Dovers’ playing of the early quartet was empathetic, subtle, impeccably phrased, marked by forward motion, drive and energy. They played up the inherent contrasts in the middle quartet’s first movement, the innocence and aspiration, warmth and solidity of the third and the controlled freneticism of the finale. But the heart of the evening was the third movement of Op.132, a work of naked supplication and beauty transformed into optimistic assertiveness. The feeling of divine well-being has rarely been better expressed. Musically mature, vibrant and uncannily unified in purpose and execution, the youthful players brought passion and grace to the first two movements, took a decisive approach to the fourth and emphasized the rhapsodic character of the finale.

TSM’s celebration of chamber music became a showcase for artists like TSO principal oboe Sarah Jeffrey, who showed off her rich tonal palette in Arthur Bliss’ Oboe Quintet Op.44, beaming like a beacon and blending in well with her string collaborators, always with grace. And pianist David Jalbert, who put his string collaborators on his back in Vaughan Williams’ Piano Quintet in C Minor, supporting and coming to the fore as needed in this vigorous, dramatic, sweetly melodic work. Two days later, Jalbert again proved a most conducive collaborator in Salomon’s arrangement of Haydn’s Symphony No.102 in B-Flat Major for keyboard, flute, two violins, viola, cello and double bass. After a rehearsal in which he felt the piano to be overpowering and excessively percussive, Jalbert had a fortepiano brought in for the concert. It made for a terrific sense of ensemble and Jalbert’s passion was contagious. The evening ended with a spirited whirl through Beethoven’s Septet in E-Flat Major Op.20 with Crow in charge, in yet another outlet for his artistry, while Nadina Mackie Jackson’s soulful bassoon provided invaluable support.

Jeffrey, Jalbert and Crow were among the more than 20 mentors to the 29 emerging artists who were members of TSM’s Academy. It’s one of the key components of the festival, one which undoubtedly has a lasting effect on all involved. Unable to attend any of the “reGeneration” concerts in which one mentor sat in with academy members for eight chamber music concerts, nor the art of song or chamber concerts by the academy members themselves, I nevertheless did get a sense of the coaching side of the festival in the masterclasses and rehearsal I witnessed.

Mezzo-soprano Sasha Cooke had several revealing ways into the music she was hearing in her masterclass: “You can’t sing Duparc until you’ve lived life and been heart-broken”; and “Art song is not painting a picture, it’s stepping into it.” In an open rehearsal, Dover Quartet first violinist Joel Link spent close to two hours working on the first movement of Sibelius’ Piano Quintet in G Minor, note by note with scrupulous attention to dynamic markings. A naturally inquisitive collaborator, he solicited ideas from his fellows and when he agreed with a suggestion, he would invariably enthuse: “Totally.”

Jonathan Crow’s masterclass was intense, generous and informative. Early on, he had so many musical ideas to impart, he spoke quickly so as to get them all out without losing time to have them executed. But he was also sensitive to the young musicians, relating stories of his own student days. When he was about their age, he found himself playing Haydn’s Quartet Op.76 No.3 (“Emperor”) with one of his heroes, Andrew Dawes, then first violinist of the original Orford String Quartet. Dawes used to record much of what he played for learning purposes. Crow had felt the performance had gone well and looked forward to hearing the playback, which turned out to be at an excessively slow speed so that every note was exaggerated.

“Jonathan,” Dawes said. “You only did four wiggles of vibrato while I did seven and a half.” Everyone in Walter Hall laughed and Crow pointed out that Dawes was noted for the clarity of his playing.

Jason Starr’s Mahler DVDs. Crow returns to his main gig on September 21 when he and the TSO under Peter Oundjian, with guest soprano Renée Fleming, open their new season with Ravel’s lush song cycle Shéhérazade, Italian arias by Puccini and Leoncavallo and songs from Rodgers and Hammerstein’s The King and I. Two days later, Henning Kraggerud is the violin soloist in Sibelius’ majestic Violin Concerto, one of the cornerstones of the repertoire. Rachmaninoff’s Symphony No.2, which drips Romanticism, completes the program. Then, on September 28 and 29, Oundjian conducts what promises to be one of the must-see concerts of the year, Mahler’s Symphony No.3; Jamie Barton, fresh from her well-received TSM recital at Koerner Hall, is the mezzo soloist alongside Women of the Amadeus Choir, Women of the Elmer Iseler Singers and Toronto Children’s Chorus.

Jason Starr’s Mahler DVDs. Crow returns to his main gig on September 21 when he and the TSO under Peter Oundjian, with guest soprano Renée Fleming, open their new season with Ravel’s lush song cycle Shéhérazade, Italian arias by Puccini and Leoncavallo and songs from Rodgers and Hammerstein’s The King and I. Two days later, Henning Kraggerud is the violin soloist in Sibelius’ majestic Violin Concerto, one of the cornerstones of the repertoire. Rachmaninoff’s Symphony No.2, which drips Romanticism, completes the program. Then, on September 28 and 29, Oundjian conducts what promises to be one of the must-see concerts of the year, Mahler’s Symphony No.3; Jamie Barton, fresh from her well-received TSM recital at Koerner Hall, is the mezzo soloist alongside Women of the Amadeus Choir, Women of the Elmer Iseler Singers and Toronto Children’s Chorus.

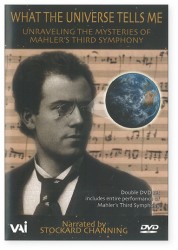

Coincidentally, I was recently given a package of Mahler DVDs produced and directed by Jason Starr, a prolific maker of dozens of video and films from classical music and modern dance performances to documentary profiles of artists and cultural issues. He began his Mahler odyssey in 2003 with a splendid deconstruction of what Mahler himself called “a musical poem that travels through all the stages of evolution.” What the Universe Tells Me: Unravelling the Mysteries of Mahler’s Third Symphony, Starr’s impressive 60-minute film, intercuts a performance by the Manhattan School of Music conducted by Glen Cortese, with analysis by baritone Thomas Hampson, scholarly talking heads like Henry-Louis de La Grange, Donald Mitchell, Peter Franklin and Morten Solvik and timely shots of the natural landscape, all in the service of furthering our understanding of Mahler’s vision. “Imagine a work so large that it mirrors the entire world,” he said.

How Schopenhauer and Nietzsche figure into Mahler’s mindset, the beginning of the cosmos, the oboe as the guide to the beauty of nature in the second movement (its notes illustrated by flowers in a high Alpine valley), are just a few examples of the myriad of details Starr and his methodical examination of this massive masterpiece reveal. Watching it (and its extras) will enhance my enjoyment of the TSO’s upcoming concert.

The same coterie of Mahlerians turn up in Starr’s most recent films completed in 2015: Everywhere and Forever: Mahler’s Song of the Earth and For the Love of Mahler: The Inspired Life of Henry-Louis de La Grange. Again Starr’s thoroughness, cinematic touches and attention to the biographical, cultural and philosophical context are invaluable for our understanding of the Song of the Earth. Since he first heard Bruno Walter conduct Mahler’s Ninth Symphony in 1945, “the symphonies of Mahler have become a world for me which I’ve never tired of exploring,” says Mahler biographer de La Grange. From the medina of Marrakech to a convent in Corsica, Toblach in South Tyrol and the Mahler Mediatheque in Paris, Starr follows de La Grange (now 91) over several years, bringing to light his passion for life and music. “Every time I hear a work of Mahler, I think I hear something I’ve never heard before,” he said. Anecdotes by Mahler’s granddaughter Marina, Boulez (“Transformation of Henry-Louis’ personality by Mahler gives him authority on Mahler.”), Chailly, Eschenbach and Hampson add to the pleasure of this essential document.

QUICK PICKS

Sept 12: Trailblazing cellist Matt Haimovitz brings his new Overtures to Bach to the intimate space of The Sound Post for a recital featuring commissioned works by Philip Glass, Du Yun, Vijay Iyer, Roberto Sierra, Mohammed Fairouz and Luna Pearl Woolf, each of which precedes a different first movement Prelude from each of Bach’s six cello suites.

Sept 14: Haimovitz brings the same program to the Kitchener-Waterloo Chamber Music Society (KWCMS). Among other performers in the Music Room of the indefatigable Narvesons this month are French cellist Alain Pierlot and pianist Jason Cutmore on Sept 25 in works by French composers (including sonatas by Debussy and Saint-Saëns). Sept 28: French pianist Alain Jacquon makes his KWCMS debut in a program of Sibelius, Ravel and Nazareth. Oct 2: Jethro Marks, principal violist of the National Arts Centre Orchestra, offers Schubert, Mendelssohn and a Beethoven violin sonata (transcribed for viola), with pianist Mauro Bertoli, currently artist-in-residence at Carlton University.

Sept 17: Stewart Goodyear takes a trip down the QEW to open the Hamilton Philharmonic Orchestra’s new season with Brahms’ first major symphonic work, the formidable Concerto No.1 in D Minor Op.15. Conductor Gemma New completes the evening with Brahms’ friend and patron, Schumann, and his visionary Symphony No.4.

Sept 17: Owen Sound’s Sweetwater Music Festival “Virtuosity” concert features clarinetist James Campbell, violist Steven Dann, percussionist Aiyun Huang, violinist (and artistic director) Mark Fewer and the Gryphon Trio in a varied program that spotlights a new commissioned work by David Braid. Sept 18: The same performers wrap up the weekend festivities with “A Classy Finish” which includes Prokofiev’s Overture on Hebrew Themes Op.34 and Beethoven’s Piano Trio in D Major (“Ghost”) Op.70 No.1.

Sept 18: For any WholeNote readers who may be in P.E.I. on the third weekend of the month, don’t miss Ensemble Made In Canada’s performance of piano quartets by Mahler, Bridge, Daniel and Brahms (No.1 in G Minor Op.25), part of the Indian River Festival.

Sept 25: Bassoon marvel Nadina Mackie Jackson is joined by string players Bijan Sepanji, Steve Koh, Rory McLeod, Bryan Lu and Joe Phillips for her “Bassoon Out Loud” season opener; works include Vivaldi’s Concerti Nos.14 & 27, Lussier’s Le Dernier Chant d’Ophélie Op.2 and works for solo strings.

Sept 30: TSO concertmaster Jonathan Crow shows his versatility as he joins with fellow TSO members, principal violist Teng Li, associate principal cellist Winona Zelenka and COC Orchestra concertmaster Marie Bérard (who comprise the Trio Arkel) to play Ligeti’s early String Quartet No.1 “Métamorphoses nocturnes.” Mozart’s masterful Divertimento in E-Flat Major K563 completes the program.

Sept 30, Oct 1: Conductor Edwin Outwater leads the Kitchener-Waterloo Symphony in two bulwarks of Romantic music: Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No.3 (with Natasha Paremski, whose temperament and technique have been compared to Argerich) and Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No.4.

Cecilia String Quartet at Mooredale

U of T Faculty of Music quartet-in-residence, the celebrated Cecilia String Quartet, opens Mooredale’s 2016/17 season September 25 with works by Haydn, Mendelssohn and Emilie LeBel. Second violinist Sarah Nematallah and cellist Rachel Desoer graciously and eloquently answered a few questions about the repertoire they will be playing in their concert at Walter Hall. I hope you enjoy their insights and that the the answers will enhance your experience of hearing them play.

WN: Please tell me about the qualities of Haydn’s Op.33 No.1 that appeal to you.

WN: Please tell me about the qualities of Haydn’s Op.33 No.1 that appeal to you.

Sarah Nematallah: I love the elusive nature of this work. There are so many moments where Haydn begins to lead you down one path and then immediately steers you in another direction - we feel momentary comfort that is quickly shaken, sweetness that suddenly turns sour, aggression that bursts into joy. I feel that this quality makes for an edge-of-your-seat experience!

WN: How does recording a work, for example the Mendelssohn Op.44 No.1, affect your subsequent performance of it?

SN: The amount and type of detail one must consider in preparing the piece and working in the recording sessions is immense. It’s intense work, but rewarding in its own way. After you’ve been through that experience, performing the piece feels very freeing - it allows you to live through the work along with the audience again, as opposed to solidifying something concrete. The experience of performing the work has a new dynamism to it that is really exhilarating.

WN: Does recording a piece focus your attention on it more than playing it in concert? Have your ideas of the piece changed or evolved since it was recorded?

SN: Recording a work requires a real commitment to one particular interpretation of a piece, and so performers must feel confident that this interpretation is something that they feel will have merit for decades to come. However, after the recording process is done, one is free to return to explore and experiment again. Sometimes it is hard to let go of the interpretation you recorded, but over time you realize that music is a fleeting artistic form that is constantly changing, and embracing that idea can give rise to interpretations you may not have thought possible in the past.

WN: How did you come to program Taxonomy of Paper Wings by Emilie LeBel?

Rachel Desoer: This piece by Emilie is part of our large project this season of Celebrating Canadian Women Composers. Over the past two years we have commissioned four outstanding women composers to write string quartets for us and this season it is all culminating. We will be presenting all four pieces at the 21C Festival in May and looking towards recording all the works. We chose Taxonomy of Paper Wings for this concert for two reasons. First, it’s a great opportunity to present Emilie’s work in her hometown. Second, her work has a calmness and a subtlety we thought would contrast greatly and provide an oasis in the middle of this busy program!

Paul Ennis is the managing editor of The WholeNote.