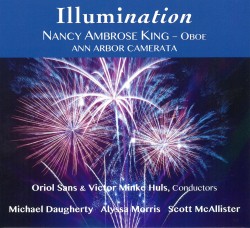

Modulations - TorQ Percussion Quartet

Modulations

Modulations

TorQ Percussion Quartet

BeDoINT Records BR004 (torqpercussion.ca)

I first heard TorQ when I took my grandkids to TorQ’s concerts for kids at Toronto’s Harbourfront. Then, in 2015, I sang in Carl Orff’s Carmina Burana with the Toronto Choral Society, TorQ providing the percussion. These guys clearly have fun performing, and it’s fun watching and listening to them.

So it is with this CD, starting with Thrown from a Loop by TorQ member Daniel Morphy. It’s just under nine minutes of music for marimbas and vibraphones, with overlapping loops “influenced,” writes Morphy, “by the music of Steve Reich.” The music has an easy swing to it, unhurried but always moving forward.

Christos Hatzis writes that his 19-minute Modulations for two vibraphones and two marimbas combines the seemingly contradictory styles of minimalism and Elliott Carter’s “metric modulation,” because “each exemplifies and needs the other for musical clarity and informational interest to ensue.” Nonetheless, instead of minimalism or Carter, Modulation’s tonal, tuneful and very jazz-inflected music distinctly reminded me of Milt Jackson’s between-the-beats magic as vibraphonist of the Modern Jazz Quartet.

The three movements of Peter Hatch’s 22-minute timespace play with various aspects of musical time and space. Time Zones presents eight different tempi simultaneously, the spatially conceived music of Spooky Action circles the audience in opposite directions, while Gravitas, writes Hatch, “is a light and humorous depiction of musical gravity” that “bends and twists our sensation of time.”

Together, nearly 50 minutes of fun listening from this very fun ensemble.