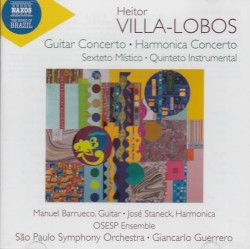

Heitor Villa-Lobos: Guitar Concerto; Harmonica Concerto - Manuel Barrueco; José Staneck; OSESP Ensemble; São Paulo Symphony Orchestra; Giancarlo Guerrero

Heitor Villa-Lobos – Guitar Concerto; Harmonica Concerto

Heitor Villa-Lobos – Guitar Concerto; Harmonica Concerto

Manuel Barrueco; José Staneck; OSESP Ensemble; São Paulo Symphony Orchestra; Giancarlo Guerrero

Naxos 8.574018 (naxos.com)

The composer Heitor Villa-Lobos is to Brazil what Bach and Beethoven are to Germany, Liszt is to Hungary and Chopin to Poland. Uniquely, Villa-Lobos also became the cellist who played many other instruments, including guitar, on which he achieved a remarkable facility. Virtuosity across many instruments also became one of Villa-Lobos’ strong suits. Burle Marx, the conductor and close friend once asked Villa-Lobos if there was anything he did not play. “Only oboe,” was the reply; but when the two met shortly afterwards, Villa-Lobos was well on his way to mastering that instrument too.

Villa-Lobos’ Guitar Concerto was commissioned by Andrés Segovia in 1951; (performed in February 1956). It is different from the bright colours and seductive melodies of Rodrigo’s Concierto de Aranjuez. But it is highly virtuosic, emotional, and explores a range of techniques including glissandi, arpeggiation and harmonics. The Harmonica Concerto is emblematic of Villa-Lobos’ cross-instrument virtuosity. The appropriately numinous Sexteto místico is imaginatively poetic and the rhapsodic and sensual Quinteto instrumental is typical of the composer’s ability to communicate with feverish Brazilian passion.

The São Paulo Symphony Orchestra, under the baton of Giancarlo Guerrero, is in exquisite form throughout, as is the OSESP Ensemble. The warmth of guitarist Manuel Barrueco’s playing – like his tone and touch – is eminently suited to Villa-Lobos’ work. Harmonica wizard José Staneck’s performance is utterly unforgettable for his ability to communicate Brazilian saudade on so tiny, albeit exquisitely chromatic, an instrument.