Bach – Harpsichord Works

Bach – Harpsichord Works

Jory Vinikour

Sono Luminus DSL-92239 (sonoluminus.com)

Comprised of four revered works, this album makes for a fine collection for harpsichord enthusiasts and fans of Johann Sebastian Bach. Jory Vinikour, two-time Grammy-nominated harpsichordist and conductor, has made quite a few recordings of Bach’s music so far and his expertise and passion for this composer is evident here. I enjoyed the clarity of Vinikour’s sound (his harpsichord is modelled after a German instrument of Bach’s time) and his refined and thoughtful interpretation. This recording has elegance and virtuosity, bringing out both the grand and hidden gestures of Bach’s compositions.

The collection features the buoyant Italian Concerto (written for two-manual harpsichord, thus distinguishing tutti from solo passages), Ouverture in French Style (consisting of eight dance movements), the exceptional Chromatic Fantasy and Fugue and an interesting pairing of the Prelude and Fugue in A-Minor BWV894 with Bach’s transcription of the Andante from Sonata for Solo Violin in A-Minor. I liked the progression of the pieces: traditional pairing of more formal works (Italian Concerto and Overture in French Style were even published together in 1835) is followed by expansion of virtuosic and improvisatory elements in Fantasy and Fugues.

Vinikour’s impeccable knowledge and sensibility to Bach’s music makes these pieces sound very personal. Listeners are granted a sonic glimpse of the unique world where the nuances are treated with care and the sound is enriched with measured restraint.

Ivana Popovic

Bach – English Suites

Bach – English Suites

Andrew Rangell

Steinway & Sons 30136 (naxosdirect.com)

If the central tenet of music-making is the desirability of singing or playing in tune, accurately producing sound waves that vibrate at the correct frequency, then no one, it seems, did this better than Johann Sebastian Bach. Much of his keyboard music was written for the harpsichord – a near-ubiquitous instrument in his day – and it began to make a seamless transition to the piano no sooner the instrument was invented and to this day continues to be wonderfully interpreted.

One of the most recent is the unveiling of the English Suites with these gorgeous, free-spirited performances by Andrew Rangell. The suites are decidedly more grandiose than the French Suites and written entirely for pleasure rather than for instruction. The allemandes are rock steady throughout, the gigues extremely lively; the courante sections rapid while the sarabandes are utterly noble. The six suites are altogether easygoing and exquisitely flowery and are said to have borne a slight resemblance to the style of Couperin, with whom Bach is known to have corresponded.

The English Suites are not actually English, but rather more influenced by other European compositional elements, that seemingly – and fortuitously – held Bach’s attention. They begin with a prelude which is often, as in the Suite No.3 in G Minor BWV808, a large-scale concerto-like movement. Rangell brings matchless clarity to Bach’s multi-stranded music. This set of discs shows the pianist at his most enjoyable, astonishingly fleet-fingered and full of delightful argumentative intelligence.

Raul da Gama

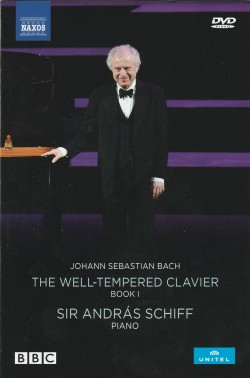

Bach – Well-Tempered Clavier Book 1

Bach – Well-Tempered Clavier Book 1

Sir András Schiff

Naxos 2.110653 (naxosdirect.com)

Bach’s renown in his own lifetime was less as a composer than as a keyboard player, both at the harpsichord and at the organ. His great ability was summarized in his obituary: “All his fingers were equally skillful; all capable of the most perfect accuracy in performance.” Today of course we know better, naturally giving due respect to the greatness of his compositions. Most notable among these – considering he was one of the greatest inventors of keyboard music – is The Well-Tempered Clavier.

The 24 preludes and fugues work through the 12 major and 12 minor keys. Unequalled in the profligacy of their inventiveness, the books were intended partly as a manual of keyboard playing and composition, partly as a systematic exploration of harmony and partly as a celebration of a new development in tuning technique that allowed the instrument to be played in any key without being retuned.

Sir András Schiff’s performance at the BBC Proms (2017) is authoritative and eminently satisfying. The fact that it has been well-crafted as a DVD is cause for additional celebration. Schiff exploits the full range of the piano’s sonorities: a crisp, hard touch is used for the more rhythmically motorized preludes, yet there are no qualms about using the sustain pedal to add colour and warmth. His speeds are slow, in some of the fugues, but the shape and direction of a piece is never in any doubt.

Raul da Gama

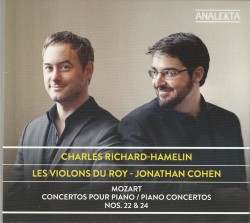

Mozart – Piano Concertos Nos.22 & 24

Mozart – Piano Concertos Nos.22 & 24

Charles Richard-Hamelin; Les Violons du Roy; Jonathan Cohen

Analekta AN 2 9147 (analekta.com)

Mozart’s spirit is (arguably) most evident in his piano-concerto writing – where vitality is entwined with gaiety, with brilliance and lyricism multilayered across. This first recording collaboration between acclaimed young pianist Charles Richard-Hamelin and Quebec City’s chamber orchestra Les Violons du Roy, led by Jonathan Cohen, captured that essence note by note. Richard-Hamelin’s fiery mastery is matched with the unwavering elegance of the orchestra’s responses while Cohen’s artistic vision underlines the most minute details of expression. Together they created a thrilling gem.

Mozart composed 11 piano concertos between February 1784 and March 1786, while living in Vienna, his creativity unrivaled by any other composer that came after him when it comes to piano concerto writing. The two concertos on this album stand on different sides of his creative expression. No.22 in E-flat Major, sometimes referred to as the queen of Mozart’s piano concertos, is stately and noble in nature, with a prominent wind section throughout. On the other end, No.24 in C Minor, is uncharacteristically emotional and dark, and is considered to be one of Mozart’s finest efforts.

I could not get enough of the beauty of Richard-Hamelin’s sound on this recording – it contains a precious combination of shimmering lightness, fluent articulation and an array of colours. Most impressive are the cadenzas he has written for these concertos, a spirited personal salute to Mozart.

Ivana Popovic

Beethoven – Piano Concertos Nos. 2 & 5

Beethoven – Piano Concertos Nos. 2 & 5

Kristian Bezuidenhout, Freiburger Barockorchester; Pablo Heras-Casados

Harmonia Mundi HMM902411 (harmoniamundi.com)

Kristian Bezuidenhout has recently turned his attention to a trilogy of Beethoven concerto discs. He is known for his inspired, imaginative and revivifying approach to fortepiano repertoire, proving time and time again that communicating brave new things at the neoclassical keyboard can be attained through good taste, apt performance practice and the right dash of courage. This first of three such recordings embodies all of these celebrated attributes and, rather triumphantly, establishes new ones.

From the vibrancy of Heras-Casado’s conducting, to the sparkling lines in winds and brass; from the marvellous sonorities revealed in Beethoven’s writing when played expertly on period instruments to the glimmering, pearl-like textures Bezuidenhout attains with unshakable, inspired finesse, this disc is absolute perfection to behold. Here is the Beethoven the world needs to know.

Brimming over with jubilant, dazzling sonic palettes, we hear musical craftsmanship on this record being set alight. The quest for innovation and (re)discovery is ever present as these gifted, impassioned artists deliver two of the best-loved piano concertos known to Western music. Bezuidenhout and Heras-Casado delight us; they astonish us, drawing us into a glorious, vivid reality from centuries gone by. In divining treasures from the past, through exceedingly hard work and a sincere love for what they do, they have set an 18th-century stage resounding with every scale, trill, arpeggio and cadence now sung afresh for the contemporary ear. Beethoven, surely, is applauding their achievement from on high.

Adam Sherkin

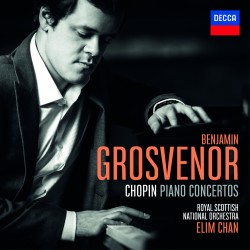

Chopin – Piano Concertos

Chopin – Piano Concertos

Benjamin Grosvenor; Royal Scottish National Orchestra; Elim Chan

Decca Records 4850365 (store.deccaclassics.com)

At 27, Benjamin Grosvenor has dazzled audiences from the very brink of his extraordinary career through to what is now his fifth release on Decca Classics.

The Royal Scottish National Orchestra itself presents formidably, with a pared down ensemble and robust presence, helmed by the intrepid Elim Chan. Her command of the players is classically clean-lined, crisp and no-nonsense in its approach to such familiar music. Both piano concerti by Chopin are often criticized for their lack of fulsome orchestra writing. However, Chan seems to disregard any longstanding notions of inadequacy in the orchestration, declaring every accompaniment episode and march-like interlude with shining surety and emphatic musicianship.

As for the solo part, Grosvenor unassumingly guides his piano to the core of each concerto’s argument, with interpretations that are commanding and forthright yet never self-indulgent. Abounding with beautiful melodies and lyrical highpoints, all of this music is aptly suited to Grosvenor’s zeal for textural clarity and elegant, quicksilver conceptions of Chopin-esque expressivity. (The first movement of No.1 and the second of No.2 are examples.) His tone and balance of phrasing remain exceedingly cultivated with a personal aspect that seems to exude a deep sense of integrity.

The poise and lucidity of Felix Mendelssohn’s keyboard writing might be a candidate for influencing Grosvenor’s approach here (and the results likely closer to Chopin’s original intentions!). No small feat it is today, to record such well-worn repertoire with fresh ears, hands – and heart.

Adam Sherkin

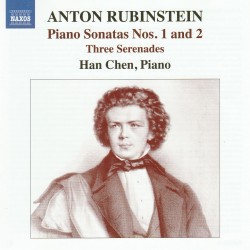

Rubinstein – Piano Sonatas Nos.1 and 2

Rubinstein – Piano Sonatas Nos.1 and 2

Han Chen

Naxos 8.573989 (naxos.com)

“Van the Second.” That’s what Franz Liszt called Anton Rubinstein, referring to his fellow pianistic titan’s resemblance to Beethoven’s unkempt, leonine looks and pile-driving keyboard aggressiveness. Like Beethoven, Rubinstein also composed in all genres but, unlike “Van the First,” he’s rarely performed today outside his native Russia.

The music on this CD dates from 1850-1855, when Rubinstein, in his early-to-mid-20s, was immersed in early Romanticism. As a teenager studying in Berlin, Rubinstein even met Mendelssohn, who is channelled in the restless, urgent first movement of Piano Sonata No.1. It’s followed by a soulful prayer, a pensive waltz and another chorale melody that ends the fourth movement, and the sonata, in grandiose fashion.

Sandwiched between the two sonatas, both lasting nearly half an hour, are the lovely, gentle Three Serenades, flavoured with subtle echoes of Chopin. Piano Sonata No. 2 is in three movements, the first two recalling Schumann in their inward, almost downcast, reflectiveness. The sonata ends much as the CD began, with a dramatic, Mendelssohnian surge of stormy energy.

Pianist Han Chen, born in Taiwan and now living in New York, was himself in his mid-20s when, in 2018, he recorded these works in King City, Ontario, with expert producers Norbert Kraft and Bonnie Silver, fine musicians themselves. Chen successfully conveys the music’s varied moods, from tender to agitated to triumphant. I found all these attractive works, though derivative, a pleasure to listen to. I think you may, too.

Michael Schuman

Debussy – Études; Children’s Corner

Debussy – Études; Children’s Corner

Aleck Karis

Bridge Records 9529 (bridgerecords.com)

Claude Debussy’s two books of Études from 1915 are less well known than many of his other piano compositions and until recently, had been neither widely performed nor recorded. Written three years before his death, they are regarded by some as his last testament to his works for piano solo, the form itself having been long embraced by such composers as Clementi, Czerny, Liszt and Chopin, to whom they are dedicated and whose music Debussy adored. The two sets are technically challenging – even the composer himself professed to struggling with certain passages – but any difficulties are met with admirable competency by the American-based pianist Aleck Karis on this Bridge recording featuring both sets and the charming Children’s Corner Suite.

Beginning with the first étude in Book 1, Pour les cing doigts, Karis displays a precise and elegant touch, his interpretations at all times thoughtfully nuanced. Indeed, these pieces, ranging in length from two minutes to just under seven, are true “studies” in contrast. The first, a tribute to Czerny, features repeated melodic progressions, while number four is moody and mysterious, and the sixth, Pour les huit doigts, a relentless perpetuum mobile.

The disc concludes with the familiar Children’s Corner Suite from 1908, a heartfelt depiction of childhood from a far simpler time. Opening with Doctor Gradus ad Parnassum, Karis’ playing is refined and sensitively articulated, with just the right amount of tempo rubato. The atmospheric Jimbo’s Lullaby would induce even the most obstinate pachyderm into slumber, while The Snow is Dancing and The Little Shepherd are true musical impressions that surely would have delighted his beloved daughter Chouchou.

Rounding out the set is the popular Golliwog’s Cakewalk, all bounce and joviality, which brings the disc to a most satisfying conclusion.

Richard Haskell

Rachmaninov; Liszt

Rachmaninov; Liszt

Luiz Carlos de Moura Castro

Independent n/a (luizdemouracastro.com)

The Brazilian pianist Luiz Carlos de Moura Castro, who plays with extraordinary virtuosity and passion, is so self-effacing that his only presence apart from the occasional entry in a digital classical music encyclopedia is on recordings, happily as brilliant as this one he produced himself. The works by Rachmaninov and Liszt – two of the greatest piano virtuosos of all time – with which he is represented here on a breathtaking-sounding Fazioli F308, are a testament to Castro’s pianistic genius.

The Liszt Piano Concerto No.2 in A Major, like everything Liszt, demands the highest level of virtuosity with its astounding octave leaps and high pianistic drama. Castro gives an overwhelmingly powerful and authoritative reading of it. His fingerwork has a steely energy to it which is remarkable. He is well supported by the Société d’Orchestre, Bienne under Jost Meier, who conducts the concerto with extraordinary and empathetic understanding of its difficult score.

Rachmaninov’s concertos are all very difficult to play and also reflect the composer’s complete technical command of the piano. Concerto No.3 in D Minor is uncommonly taxing and No.2 in C Minor is filled with bravura. Castro brings to life both of these – as well as Liszt’s Rhapsody on a Theme by Paganini, a work almost as capricious as anything Paganini himself wrote – with the Slovenia Radio and TV Symphony Orchestra, the fiery Ligia Amadio conducting brilliantly.

Raul da Gama

Percy & Friends

Percy & Friends

Richard Masters

Heritage HTGCD 179 (richard-masters.com)

“Let us go then, you and I, / When the evening is spread out against the sky…” Let us listen then, of summer evenings, nightingales and shepherd’s hey; of rainbow trout, bridal lullabies and colonial songs. Pianist Richard Masters offers an attractive new disc, celebrating varied solo piano pieces from an unexpected cohort: Roger Quilter, Henry Balfour Gardiner, Cyrill Scott, Norman O’Neill, Frederick Delius and Percy Grainger.

Such English-speaking expatriates who were, at one time, all in school together at the Hoch Conservatory, Frankfurt, became known as the Frankfurt Group, not including Frederick Delius. The other five revered Delius and often subsumed him in various articles written about the composers during their time: the New English School was profiled as an adventurous collective of young musical artists, Anglo-centric and German-despising.

The 17-track record from Masters, in combination with his fine liner notes, transports the listener to a gentle world of breezy morning strolls and wholesome sips of afternoon tea. This aesthetic never seeks to poke or to prod, nor to unseat the status quo; here is a unique strain of harmonic connectedness, always sumptuous in its tonal narrative. From such discarded chests of keyboard music emanates a sincerity of lyricism, generously set against tableaux of perfumed sonic spaces. With comely confidence and a slightly perceptible dash of American Southern charm, Masters cajoles you and me, as he brings this New English School of the early 20th century back to life.

Adam Sherkin

Prokofiev – Piano Sonatas Nos. 6, 7 & 8

Prokofiev – Piano Sonatas Nos. 6, 7 & 8

Steven Osborne

Hyperion CDA688298 (hyperion-records.co.uk)

With three gritty, strenuous piano sonatas that run the gamut of expression in movements now dreamy and languid, now pungent and divisive, Scottish pianist Steven Osborne proves yet again that he can tackle any corner of the piano repertory with technical prowess and innate stylistic aplomb.

In this new disc, Osborne rips into some of the most challenging keyboard music ever written by Russian composer Sergei Prokofiev. The challenges here extend far beyond the thorniness of the sonatas’ character and their assembled identity as three war sonatas, (Opp.82, 83 and 84), written during the years 1939 through 1944. These broad and complex works demand an acute understanding of modernist expression and its concept of human experience when stretched to the very edge. This edge can be extreme in some cases, compelling both listener and pianist alike to embrace the ridiculous as well as the sublime. A successful performance of such music depends on the wits (and technique!) of a multi-versed artist up to the challenge. Osborne leaves us with no doubt as to our emotional survival: we immediately jump onboard for the ride, putting ourselves in his safekeeping until the end of this disc. Therein, Osborne’s hands cast spells of colour and light that echo the deft craft of impressionist composers, betraying a kinship (rarely revealed) between the inspired music of turn-of-the-century France and that generation of Russian modernists who emerged in the 1920s, with Prokofiev at the vanguard.

Adam Sherkin

Samuil Feinberg – Piano Sonatas Nos. 1-6

Samuil Feinberg – Piano Sonatas Nos. 1-6

Marc-André Hamelin

Hyperion CDA 68233 (hyperion-records.co.uk)

Wondrous and fair, is the music of Russian composer-pianist, Samuil Feinberg. Today, 58 years after his death, he remains little known outside of Russia. Nevertheless, veteran virtuoso Marc-André Hamelin has long championed the ravishing piano catalogue of Feinberg, peppering his own recital programs with his music. Now, for the first time in a truly voluminous discography, Hamelin has recorded six sonatas by Feinberg, Opp.1, 2, 3, 6, 10 and 13. Each one is a marvel of pianistic craft, gazing down from the pinnacle of early 20th-century Russian lineage.

Both the first and second sonatas owe a great deal to the spectrums of resonance and open-hearted romanticism found in Rachmaninoff’s piano writing, (in particular the Sonata No.2 in B-flat Minor Op.36). These works gleam with whimsical, searching melodies, buoyed up by formidable textures. Hamelin aptly leads the adventure, taking the utmost care and cultivation. In fact, Hamelin navigates every page of these fascinating, singular pieces with splendid ease and confidence. He finds ways to personalize the expressive potential Feinberg embeds in his scores.

Another highlight of the disc, Feinberg’s Sonata No.5, invites us into an eerie, unsettled world. The opening rollicks with overwrought chords that grope and sniff their way through the dark. What – or whom – might they be seeking? This disc bears repeated listening, as is so often the case with Hamelin’s artistry. Verily, today’s musical world would be a dimmer place without him.

Adam Sherkin

Dvořák – Symphony No.9; Copland – Billy the Kid

Dvořák – Symphony No.9; Copland – Billy the Kid