A century ago we removed the boundaries that defined the general order of things in our world. Notions of social class, religious belief and art all flowed into a sea of mixing currents as we challenged ourselves to be comfortable with things much less clear than once had been. Composers, like painters, developed a powerful, post-Romantic language that guided the human experience of art beyond intellect and emotion and into something of an altered state. Less concerned with linear argument than impression, composers like Debussy mastered the vocabulary of other worlds and left us a creative legacy that has scarcely aged a day. So it seems natural that a contemporary musician like Kathleen Supové should commission a project from a group of seven 21st-century composers asking how the music of Claude Debussy has shaped their art, The Debussy Effect (New Focus Recordings FCR170).

A century ago we removed the boundaries that defined the general order of things in our world. Notions of social class, religious belief and art all flowed into a sea of mixing currents as we challenged ourselves to be comfortable with things much less clear than once had been. Composers, like painters, developed a powerful, post-Romantic language that guided the human experience of art beyond intellect and emotion and into something of an altered state. Less concerned with linear argument than impression, composers like Debussy mastered the vocabulary of other worlds and left us a creative legacy that has scarcely aged a day. So it seems natural that a contemporary musician like Kathleen Supové should commission a project from a group of seven 21st-century composers asking how the music of Claude Debussy has shaped their art, The Debussy Effect (New Focus Recordings FCR170).

Listening to these works in this context, they are all clearly tributes to the French impressionist, although some more tenuously than others. Still, there’s plenty of originality in this repertoire and Supové plays wonderfully, whether with or without electronic effects. Jacob Cooper’s La plus que plus que lent slows down Debussy’s waltz significantly as it plays with fragments of the original. Cakewalking (Sorry Claude) by Daniel Felsenfeld is especially creative in its unmistakable rhythms and occasional quotes from Debussy’s Golliwog’s Cakewalk.

The most effective work may well be Randall Woolf’s What Remains of a Rembrandt. Here the composer argues that the essence of Debussy is the element of mystery. Supové’s playing demonstrates a complete understanding of how Woolf sets out to render this element and achieves exactly what both he and Debussy would have intended.

The Debussy Effect is a bold and creative project that is as admirably clever as it is superbly performed.

American composer Bruce Adolphe is often inspired by very contemporary social and political issues, and so it is that his latest recording, Bruce Adolphe – Chopin Dreams (Naxos 8.559805) is a little unusual.

American composer Bruce Adolphe is often inspired by very contemporary social and political issues, and so it is that his latest recording, Bruce Adolphe – Chopin Dreams (Naxos 8.559805) is a little unusual.

The recording’s title work is an impression of how Chopin might compose today were he a jazz musician playing in a New York club. Adolphe does an artful job of borrowing Chopin’s distinctive keyboard language. He replicates the melancholy harmonies, the cascading right-hand arpeggios, the ornaments and filigree that we uniquely associate with the composer. He also writes in the forms that make up much of Chopin’s repertoire, the prelude, nocturne, mazurka and other dances.

While the premise of Chopin as a New York Jazz club pianist offers a comic element to be sure, it’s quickly dispelled by the highly informed and engaging nature of Chopin Dreams. Jazzurka, New York Nocturne, Quaalude and the other items in the set unmistakably use Chopin’s vocabulary. Even so, the frequent presence of the blue note seems entirely appropriate for Chopin, given his affection for the richness of minor keys.

Considerably more serious is Adolphe’s recent work Seven Thoughts Considered as Music (2016). Using short quotes from seven thinkers including Emerson, Chief Seattle and Kafka, Adolphe explores the transfer of deeper meaning to the voice of the piano. There’s great substance to these pieces and they merit more than one hearing.

Italian pianist Carlo Grante plays the newly redesigned Bösendorfer 280VC concert grand on this CD and has a great deal of fun with the nine Piano Puzzlers, short pieces that Adolphe regularly composes and performs on the American Public Radio program Performance Today. Familiar tunes like Deck The Hall, The Streets of Laredo and many others are set in the unmistakable style of Chopin’s best-known pieces, leaving listeners grinning at the composer’s imitative wizardry.

Horacio Gutiérrez is a respected pedagogue and performer. His newest recording, Chopin 24 Preludes, Op.28; Schumann Fantasie Op.17 (Bridge 9479), is an impressive example of his playing. Never short of powerful expression and blazing speed at the keyboard, he is also capable of the tenderest phrasings required in Chopin’s 24 Preludes Op. 28. Each of these short pieces (some merely a half minute) is a complete idea that Gutiérrez treats as though it were entirely independent. Still, the progression of keys is logical and patterned, and so he holds the collection together for performance as a larger utterance. Many argue this was, in fact, Chopin’s intent.

Horacio Gutiérrez is a respected pedagogue and performer. His newest recording, Chopin 24 Preludes, Op.28; Schumann Fantasie Op.17 (Bridge 9479), is an impressive example of his playing. Never short of powerful expression and blazing speed at the keyboard, he is also capable of the tenderest phrasings required in Chopin’s 24 Preludes Op. 28. Each of these short pieces (some merely a half minute) is a complete idea that Gutiérrez treats as though it were entirely independent. Still, the progression of keys is logical and patterned, and so he holds the collection together for performance as a larger utterance. Many argue this was, in fact, Chopin’s intent.

Unlike Bach’s 48 Preludes and Fugues, these are not studies or practice pieces. Nor are they preludes to anything as one writer once famously queried. Instead they are best received as a kind of pianistic haiku. Short, self-contained and entirely complete.

Gutiérrez plays with a great deal of disciplined freedom that remains in control of the emotional content through a very precise keyboard technique. This is especially important for the Schumann Fantasie Op.17 where the great contrasts in mood are vital to the work’s impact. The middle sections of the second and third movements demonstrate this wonderfully as does the final, tranquil ending. Every note and phrase is perfectly placed. There is no excess. All is in perfect balance.

Gutiérrez’s students at the Manhattan School, where he currently teaches, are fortunate to have such a mentor.

Second-place winner of the 17th International Chopin Piano Competition in 2015, Charles Richard-Hamelin’s live performances on Chopin Sonata B Minor Op.58; Nocturnes (The Fryderyk Chopin Institute, Polish Radio NIFCCD 617-618) demonstrate why he impressed the panel of judges so profoundly. Perhaps more than anything, Richard-Hamelin plays as if no one else were present, firmly connected to the core of the music and completely given over to it. His technique is impeccable and his interpretive decisions mature and credible. Moreover, he manages to inject subtleties into his performances that would catch the judges’ attention. Micro hesitations, refinements of standard dynamics, tempo relaxations, all give his playing of well-worn works originality and freshness.

Second-place winner of the 17th International Chopin Piano Competition in 2015, Charles Richard-Hamelin’s live performances on Chopin Sonata B Minor Op.58; Nocturnes (The Fryderyk Chopin Institute, Polish Radio NIFCCD 617-618) demonstrate why he impressed the panel of judges so profoundly. Perhaps more than anything, Richard-Hamelin plays as if no one else were present, firmly connected to the core of the music and completely given over to it. His technique is impeccable and his interpretive decisions mature and credible. Moreover, he manages to inject subtleties into his performances that would catch the judges’ attention. Micro hesitations, refinements of standard dynamics, tempo relaxations, all give his playing of well-worn works originality and freshness.

Despite the fact that the pieces were recorded at various sessions, the three auditions and the final concert, it would have been evident early on that Richard-Hamelin was a serious contender for one of the top spots in this race. Disc one of this 2-CD set closes with the Rondo in E Flat Major Op.16. It’s a piece that uses almost every one of Chopin’s devices and Richard-Hamelin sails through them effortlessly, never showing fatigue or anything less than total focus on the artistic demands of the work.

Disc two features a few more smaller pieces but offers the B Minor Sonata Op.58 as its major work. Richard-Hamelin’s capable grasp of its wide-ranging demands earned him his winning spot plus the Krystian Zimerman prize for the best performance of a sonata.

The 2015 17th International Chopin Piano Competition was the first time Canada had appeared in the rankings in the competition’s history.

Lars Vogt’s new recording, Schubert – Impromptus, D899, Moments Musicaux D780, Six German Dances D820 (Ondine ODE 1285-2) offers familiar repertoire although with a detectable inward focus.

Lars Vogt’s new recording, Schubert – Impromptus, D899, Moments Musicaux D780, Six German Dances D820 (Ondine ODE 1285-2) offers familiar repertoire although with a detectable inward focus.

The liner notes include a wonderful interview with Vogt in which he reveals his personal thoughts on Schubert and the repertoire in this recording. It’s worthwhile and instructive to read about the intellectual process behind the creative one.

Vogt has a unique style at the keyboard. It’s one that has all the warmth and romanticism to express Schubert’s most heartfelt passages, yet also includes a sharp, bright exclamatory touch that can be as brief as a single note or sometimes carry an entire phrase. This plays nicely against the otherwise mellow nature of Schubert’s rich harmonies.

The Six German Dances, in particular, are surprisingly tender in Vogt’s hands. Here he argues for an approach that is truer to the original style of the pieces, more down to earth and tender, perhaps even pointing to the convivial bliss of simple country folk.

The familiarity of the Impromptus D899 makes them a special challenge. Vogt does a terrific job with them all, but really makes No.4 stand out with his remarkably light staccato on all the descending runs in the treble.

The Moments Musicaux D780, too, are favourites and require something to make them distinctive. No.6 is often played with far more contrast than Vogt brings to this performance. Instead, he opts for a more wistful approach throughout and it works well. Overall, Vogt seems to raise the bar on everything without ever going too far. It’s an impressive process of balance and taste that has produced a very satisfying recording for Schubert collectors.

Jean-Efflam Bavouzet has completed his recording of the Beethoven piano sonatas with the release of Beethoven Piano Sonatas Vol. 3 (Chandos CHAN 10925(3)). Do we need another Beethoven Sonata cycle? Bavouzet occupied himself with this very question before committing to the project for Chandos. Those who know and cherish these works will each have favourite interpreters who have revealed new meaning in them. Bavouzet argues that projects like this are evolutionary and therefore benefit from all those that preceded them.

Jean-Efflam Bavouzet has completed his recording of the Beethoven piano sonatas with the release of Beethoven Piano Sonatas Vol. 3 (Chandos CHAN 10925(3)). Do we need another Beethoven Sonata cycle? Bavouzet occupied himself with this very question before committing to the project for Chandos. Those who know and cherish these works will each have favourite interpreters who have revealed new meaning in them. Bavouzet argues that projects like this are evolutionary and therefore benefit from all those that preceded them.

As a mature artist in his mid-50s, Bavouzet indeed has something to say and he says it convincingly. His performance of the Sonata Op.57 “Appassionata” is surprisingly understated through most of the second movement. This heightens the impact of the final movement which follows very aggressively without a break. His speed and precision seem effortless. He shapes Beethoven’s phrases intelligently and manages to keep the composer’s impetuous nature teeming without boiling over.

The Sonata Op.106 “Hammerklavier” is the towering, complex work after whose final measures, a sonata cycle like this either succeeds or crumbles. Bavouzet emerges in this performance as an artist fully capable of embracing the essence of what Beethoven had to say, and how to say it. Bavouzet’s revelation in this repertoire is that Beethoven was not a mad composer pouring magnificent anger from his pen. Rather, he was an impassioned genius crafting everything with an exacting science rooted in his soul. Bavouzet obviously “gets” Beethoven – in the profoundest way.

In addition to his stature as a Liszt interpreter, Nicolas Horvath devotes a considerable amount of his career energy to contemporary music. The new release Glassworlds • 5: Enlightenment (Grand Piano GP745) continues his recordings of the piano music of Philip Glass.

In addition to his stature as a Liszt interpreter, Nicolas Horvath devotes a considerable amount of his career energy to contemporary music. The new release Glassworlds • 5: Enlightenment (Grand Piano GP745) continues his recordings of the piano music of Philip Glass.

Two large, major works nearly fill this disc. Mad Rush, written in 1979 as a commissioned organ piece under a different title, has since been renamed and performed as dance accompaniment as well as a piano solo. Glass performed it himself several times and perhaps most interestingly as music for the entry of the 14th Dalai Lama into the Cathedral of St. John the Divine.

600 Lines is a 40-minute piece built on just five pitches played in varying rhythmic patterns constantly shifting emphasis on principal notes in those patterns. If you’re acquainted with the English bell ringing tradition of “ringing changes,” this piece will surprisingly make a lot of sense.

Considerably shorter but no less engaging is Metamorphoses (5): No. 2. The work had never been published, so Horvath naturally takes some pride in performing its world premiere as a solo piano work. Horvath clearly has a deep affection for Glass’ music that goes far beyond the intellectual. His grasp of it is both passionate and revealing.

In writing his own, excellent liner notes for this recording, Horvath closes by quoting the composer, “Music is a social activity…Music is a transaction; it passes between us.”

The most exotic item in this month’s collection is Keiko Shichijo’s new release Komitas Vardapet – Six Dances (Makkum Records MR.17/Pb006). It’s as unusual for its repertoire, as it is for its brevity, a mere eighteen minutes. The dances are based on Armenian folk melodies which the composer transcribed from original settings for folk instruments. Komitas is said to have notated some 3,000 Armenian folk tunes; only 1,200 survive.

The most exotic item in this month’s collection is Keiko Shichijo’s new release Komitas Vardapet – Six Dances (Makkum Records MR.17/Pb006). It’s as unusual for its repertoire, as it is for its brevity, a mere eighteen minutes. The dances are based on Armenian folk melodies which the composer transcribed from original settings for folk instruments. Komitas is said to have notated some 3,000 Armenian folk tunes; only 1,200 survive.

Although an ordained priest, his work as an ethnomusicologist has made him an icon in the history of Armenian culture. His exposure to Western European music came from his studies in Berlin at the end of the 19th century. Shichijo chose to record his solo piano work Six Dances after performing some of his other compositions with a chamber ensemble. She is remarkably persuasive in the way she portrays the percussive, and otherwise non-Western, stylings of this music. It’s nearly all monodic, just a single melody line, sometimes in octaves, against the barest of accompaniments. There’s a definite feel of Debussy’s exoticism about Komitas’ music.

While it’s a modest recording effort, it’s a beautiful fusion of worlds that creates the temptation to hear more of this composer’s repertoire.

Review

American composer Jack Gallagher claims the piano is not his principal instrument, but his apology evaporates as soon as you hear his music. In Jack Gallagher Piano Music (Centaur CRC 3522) pianist Frank Huang captures the colour and imagination of Gallagher’s writing whether in works lighthearted or those more cerebral.

American composer Jack Gallagher claims the piano is not his principal instrument, but his apology evaporates as soon as you hear his music. In Jack Gallagher Piano Music (Centaur CRC 3522) pianist Frank Huang captures the colour and imagination of Gallagher’s writing whether in works lighthearted or those more cerebral.

Gallagher writes with a great care for structure. Form and planning are important to him. This makes his works easy to navigate for both listener and performer while he evolves his more complex musical material.

Huang plays this repertoire with ease and familiarity. Works like the Sonata for Piano are very technically demanding as is Malambo Nouveau. Others like Six Bagatelles and Sonatina for Piano, less so. Still, works like Six Pieces for Kelly, written specifically for young performers, never lack for a mature and profoundly musical touch. Every so often a Gershwin-like harmony slips by, leaving an echo of Broadway and a reminder of how American this music is.

Huang’s performance is confident, bold and celebratory; Gallagher’s writing seems to induce those qualities. This recording is a perfect match between composer and performer.

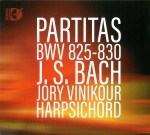

Harpsichordist Jory Vinikour has released Partitas BWV 825-830 J.S. Bach (Sono Luminus DSL-92209), a wonderful example of how varied and engaging Bach can be at the harpsichord. If you need an introduction to Bach, then his 1731 self-published Opus 1 is a good place to start.

Harpsichordist Jory Vinikour has released Partitas BWV 825-830 J.S. Bach (Sono Luminus DSL-92209), a wonderful example of how varied and engaging Bach can be at the harpsichord. If you need an introduction to Bach, then his 1731 self-published Opus 1 is a good place to start.

Using a two-manual instrument built in 1995 on the scheme of a 1738 German harpsichord, Vinikour takes very deliberate time to play through the six Partitas in this three-disc set. While most items in the Partitas are labelled as dance movements, some offer a very different character and Vinikour is careful to find and exploit the essence of each piece.

The Toccata of Partita No.6 in E Minor BWV830 opens and closes with waves of fantasia-like arpeggios that are a sharp contrast to the highly ordered material between them. The Overture of Partita No.4 in D Major BWV 828 begins with an extended statement that offers all the drama of an opera before moving into the discipline of a fugue. The following Allemande is a beautiful and languorous melodic wander through Bach’s harmonic world. Vinikour knows this territory well, using every technical and interpretive device to maximum effect. He knows how far to push the limits of free Baroque forms as well as complying with the rigours of Bach’s fugal treatments.

On a technical note, the recording uses terrific stereo separation that’s very effective.