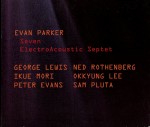

Just as international improvisers sometimes find a more welcoming atmosphere for their sound experiments in Canada than at home, so too have Canadian record labels become a vehicle to release notable free music sessions. Attesting to this openness, two of the most recent discs by British saxophone master Evan Parker are on Canadian imprints. But each arrived by a different route. One of the triumphs of 2014’s Festival International de Musique Actuelle de Victoriaville in Quebec, this performance of Seven by Parker’s ElectroAcoustic Septet (Victo 127 victo.qc.ca) is available on Victo, FIMAV’s affiliated imprint. Consisting of one massive and one shorter instant composition, Seven literally delineates the electro-acoustic divide. Trumpeter Peter Evans, reedist Ned Rothenberg, cellist Okkyung Lee and Parker make up the acoustic side, while varied laptop processes are operated by Ikue Mori and Sam Pluta, with George Lewis switching between laptop and trombone, with his huffing brass tone making a particular impression during a contrapuntal face-off with Parker’s soprano saxophone during Seven-2. At nearly 46 minutes, Seven-1 is the defining work, attaining several musical crests during its ghostly, meandering near-time suspension. Allowing for full expression of instrumental virtuosity, dynamic flutters, flanges and processes, the laptoppists accompany, comment upon or challenge the acoustic instruments. Alternately wave form loops and echoes cause the instrumentalists to forge their reposes. Plenty of sonic surprises arise during the sequences. Undefined processed-sounding bee-buzzing motifs, for example, are revealed as mouth and lip modulations from Evans’ piccolo trumpet or aviary trills from Rothenberg’s clarinet. In contrast the electronics’ crackles and static are often boosted into mellower affiliations that sound purely acoustic. Eventually both aspects meld into a climax of bubbly consistency with any background-foreground, electro or acoustic displays satisfactorily melded. More percussive Seven-2 has a climax involving fragmented electronics pulsating steadily as first Evans, then Rothenberg and finally Parker spill out timbres that confirm formalism as much as freedom.

Just as international improvisers sometimes find a more welcoming atmosphere for their sound experiments in Canada than at home, so too have Canadian record labels become a vehicle to release notable free music sessions. Attesting to this openness, two of the most recent discs by British saxophone master Evan Parker are on Canadian imprints. But each arrived by a different route. One of the triumphs of 2014’s Festival International de Musique Actuelle de Victoriaville in Quebec, this performance of Seven by Parker’s ElectroAcoustic Septet (Victo 127 victo.qc.ca) is available on Victo, FIMAV’s affiliated imprint. Consisting of one massive and one shorter instant composition, Seven literally delineates the electro-acoustic divide. Trumpeter Peter Evans, reedist Ned Rothenberg, cellist Okkyung Lee and Parker make up the acoustic side, while varied laptop processes are operated by Ikue Mori and Sam Pluta, with George Lewis switching between laptop and trombone, with his huffing brass tone making a particular impression during a contrapuntal face-off with Parker’s soprano saxophone during Seven-2. At nearly 46 minutes, Seven-1 is the defining work, attaining several musical crests during its ghostly, meandering near-time suspension. Allowing for full expression of instrumental virtuosity, dynamic flutters, flanges and processes, the laptoppists accompany, comment upon or challenge the acoustic instruments. Alternately wave form loops and echoes cause the instrumentalists to forge their reposes. Plenty of sonic surprises arise during the sequences. Undefined processed-sounding bee-buzzing motifs, for example, are revealed as mouth and lip modulations from Evans’ piccolo trumpet or aviary trills from Rothenberg’s clarinet. In contrast the electronics’ crackles and static are often boosted into mellower affiliations that sound purely acoustic. Eventually both aspects meld into a climax of bubbly consistency with any background-foreground, electro or acoustic displays satisfactorily melded. More percussive Seven-2 has a climax involving fragmented electronics pulsating steadily as first Evans, then Rothenberg and finally Parker spill out timbres that confirm formalism as much as freedom.

While Seven’s domestic release seems almost mandatory, Montreal-based Red Toucan’s decision to release UK-recorded Extremes (RT 9349 symaptico.ca/cactus.red) demonstrates its commitment to this music. Parker on tenor saxophone, alongside Paul Dunmall, another intense British tenor specialist, plus American drummer Tony Bianco, offer a three-track masterclass in free-form improvisation. With the drummer keeping up a constant barrage of smacks, whacks, ruffs and pops in the propulsive Elvin Jones tradition, the saxophonists dig into every variation and shading of reed and metal tones like an updated John Coltrane and Pharoah Sanders. Unlike the maelstrom of bedlam-like expression in which some sound explorers operate, however, Dunmall and Parker play with relaxed intensity. This isn’t a cutting contest either, but a demonstration of how saxophonists can function as separate parts of a single entity. With the final Horus especially adding affirming motes to the jazz tradition via glossolalia and faint echoes of Sonny Rollins’ East Broadway Rundown, each player maintains his individuality no matter how many harsh snorts or siren-pitched expressions are unleashed. Parker’s tone is distinguished by lighter vibrations and swifter split tones while Dunmall’s timbres are darker and grittier. With intuitive timing the tenors attain concluding connection, showcasing rowdy theme variations on the 30-minute-plus title track and polyphonic expressiveness on Horus. Overall, the result is head expanding, not head banging.

While Seven’s domestic release seems almost mandatory, Montreal-based Red Toucan’s decision to release UK-recorded Extremes (RT 9349 symaptico.ca/cactus.red) demonstrates its commitment to this music. Parker on tenor saxophone, alongside Paul Dunmall, another intense British tenor specialist, plus American drummer Tony Bianco, offer a three-track masterclass in free-form improvisation. With the drummer keeping up a constant barrage of smacks, whacks, ruffs and pops in the propulsive Elvin Jones tradition, the saxophonists dig into every variation and shading of reed and metal tones like an updated John Coltrane and Pharoah Sanders. Unlike the maelstrom of bedlam-like expression in which some sound explorers operate, however, Dunmall and Parker play with relaxed intensity. This isn’t a cutting contest either, but a demonstration of how saxophonists can function as separate parts of a single entity. With the final Horus especially adding affirming motes to the jazz tradition via glossolalia and faint echoes of Sonny Rollins’ East Broadway Rundown, each player maintains his individuality no matter how many harsh snorts or siren-pitched expressions are unleashed. Parker’s tone is distinguished by lighter vibrations and swifter split tones while Dunmall’s timbres are darker and grittier. With intuitive timing the tenors attain concluding connection, showcasing rowdy theme variations on the 30-minute-plus title track and polyphonic expressiveness on Horus. Overall, the result is head expanding, not head banging.

A trio concerned with the linkage between notated and improvised sounds is Lisbon-based, EarNear; its self-titled debut CD appears on the Rimouski-based TourdeBras label (TDB90012 CD tourdebras.com). Conversant in many genres, violist João Camões, pianist Rodrigo Pinheiro and cellist Miguel Mira expose textures unique and unexpected for a chamber ensemble. Although strident, speedy and high pitched much of the time, generic continuum is maintained with Mira connectively thumping out what would be the bassist’s role in jazz. On the other hand barbed wire-like sharpened sweeps from Camões, plus inner piano plinks, plucks and crackles confirm the modernity of the performance on tracks such as Airfoil. The responsive nature of the trio’s narrative is such though, that even Gõmbõc, the lengthiest and most cerebral performance, is tempered with sympathetic piano chording and bass string pressure. This leads to a tonal resolution of what begins as a cacophonous battle, with rugged low-pitched string scrubbing on one side and euphonious textures expressed in bell-like, near-harpsichord vibrations on the other.

A trio concerned with the linkage between notated and improvised sounds is Lisbon-based, EarNear; its self-titled debut CD appears on the Rimouski-based TourdeBras label (TDB90012 CD tourdebras.com). Conversant in many genres, violist João Camões, pianist Rodrigo Pinheiro and cellist Miguel Mira expose textures unique and unexpected for a chamber ensemble. Although strident, speedy and high pitched much of the time, generic continuum is maintained with Mira connectively thumping out what would be the bassist’s role in jazz. On the other hand barbed wire-like sharpened sweeps from Camões, plus inner piano plinks, plucks and crackles confirm the modernity of the performance on tracks such as Airfoil. The responsive nature of the trio’s narrative is such though, that even Gõmbõc, the lengthiest and most cerebral performance, is tempered with sympathetic piano chording and bass string pressure. This leads to a tonal resolution of what begins as a cacophonous battle, with rugged low-pitched string scrubbing on one side and euphonious textures expressed in bell-like, near-harpsichord vibrations on the other.

Golden State II’s (SGL 1610-2 songlines.com) situation is atypical since drummer Harris Eisenstadt is a Canadian and Songlines is a Vancouver imprint. But Eisenstadt is based in Brooklyn and other members of this working quartet – bassist Mark Dresser, bassoonist Sara Schoenbeck and clarinetist Michael Moore – are Americans, natives of California: the Golden State. Here much of the emphasis builds on the divergences between Schoenbeck’s rhinal smears and Moore’s honeyed trills. For example, Agency, a near blues, validates the bassoon as a frontline instrument with hard gusts from Schoenbeck’s horn doubled by Moore as the theme is propelled by rim shots and double bass stops. A Kind of Resigned Indignation is an analogous showcase for Dresser’s profound facility, as he moves from sul ponticello minutiae to focused walking, maintaining bedrock toughness while spurring the others. Defining chamber jazz much differently than EarNear does, the drummer’s knocks and sweeps give the CD a rhythmic base propelled with sophisticated understatement. Animatedly reaching a climax of suspended time on Seven in Six/A Particularity with a Universal Resonance, the quartet blends reed smoothness, curlicue percussion pops and string sweeps into a distinct chromatic form. The result is as mellow, unhurried and sunny as the Golden State or Vancouver.

Golden State II’s (SGL 1610-2 songlines.com) situation is atypical since drummer Harris Eisenstadt is a Canadian and Songlines is a Vancouver imprint. But Eisenstadt is based in Brooklyn and other members of this working quartet – bassist Mark Dresser, bassoonist Sara Schoenbeck and clarinetist Michael Moore – are Americans, natives of California: the Golden State. Here much of the emphasis builds on the divergences between Schoenbeck’s rhinal smears and Moore’s honeyed trills. For example, Agency, a near blues, validates the bassoon as a frontline instrument with hard gusts from Schoenbeck’s horn doubled by Moore as the theme is propelled by rim shots and double bass stops. A Kind of Resigned Indignation is an analogous showcase for Dresser’s profound facility, as he moves from sul ponticello minutiae to focused walking, maintaining bedrock toughness while spurring the others. Defining chamber jazz much differently than EarNear does, the drummer’s knocks and sweeps give the CD a rhythmic base propelled with sophisticated understatement. Animatedly reaching a climax of suspended time on Seven in Six/A Particularity with a Universal Resonance, the quartet blends reed smoothness, curlicue percussion pops and string sweeps into a distinct chromatic form. The result is as mellow, unhurried and sunny as the Golden State or Vancouver.

Canadian labels’ openness to experimentation goes back at least to the early 1970s, with Sackville’s series of Toronto-recorded original sessions featuring then-emerging players from Chicago and New York. Reissued with two additional tracks, 1974’s Trio and Duet (Sackville/Delmark SK3007 delmark.com) hints at why Anthony Braxton’s vision may have been too difficult for some jazz fans of the time. Accompanied by bassist Dave Holland and playing alto saxophone on five tracks, Braxton creates his own variations of standards. While his stripped-down performances may appear slightly frenetic compared to mainstream versions, despite solid timekeeping and a triple-slicing showcase from the bassist on You Go to My Head, the melody remains. If tracks such as Embraceable You or On Green Dolphin Street include more altissimo slurs or squeaking sheets of sound than were common four decades ago, in 2015 the versions would frighten only the most hidebound neo-cons. Yet if Braxton’s standards side was accepted he turns around on what was the LP’s other side and creates a 19-minute modernist piece titled HM-421 (RTS) 47, featuring himself on clarinet, contrabass clarinet, chimes and percussion, Leo Smith on pocket trumpet, trumpet, flugelhorn and percussion plus Richard Teitelbaum on Moog synthesizer, with textures the keyboardist pioneered as a member of Musica Elettronica Viva. Spatial and carefully sequenced, the Moog’s flanges set up a juddering, staccato ostinato over which Smith and Braxton layer muted peeps and stentorian puffs plus chime and conga-like pumps. Yet even if Teitelbaum’s oscillations resemble a Model T warming up rather than the futuristic electronics of today, the graceful playing expressed by all means that at this early date Braxton and the others had perfected the subtle art of matching electronic and acoustic textures without conflict.

Canadian labels’ openness to experimentation goes back at least to the early 1970s, with Sackville’s series of Toronto-recorded original sessions featuring then-emerging players from Chicago and New York. Reissued with two additional tracks, 1974’s Trio and Duet (Sackville/Delmark SK3007 delmark.com) hints at why Anthony Braxton’s vision may have been too difficult for some jazz fans of the time. Accompanied by bassist Dave Holland and playing alto saxophone on five tracks, Braxton creates his own variations of standards. While his stripped-down performances may appear slightly frenetic compared to mainstream versions, despite solid timekeeping and a triple-slicing showcase from the bassist on You Go to My Head, the melody remains. If tracks such as Embraceable You or On Green Dolphin Street include more altissimo slurs or squeaking sheets of sound than were common four decades ago, in 2015 the versions would frighten only the most hidebound neo-cons. Yet if Braxton’s standards side was accepted he turns around on what was the LP’s other side and creates a 19-minute modernist piece titled HM-421 (RTS) 47, featuring himself on clarinet, contrabass clarinet, chimes and percussion, Leo Smith on pocket trumpet, trumpet, flugelhorn and percussion plus Richard Teitelbaum on Moog synthesizer, with textures the keyboardist pioneered as a member of Musica Elettronica Viva. Spatial and carefully sequenced, the Moog’s flanges set up a juddering, staccato ostinato over which Smith and Braxton layer muted peeps and stentorian puffs plus chime and conga-like pumps. Yet even if Teitelbaum’s oscillations resemble a Model T warming up rather than the futuristic electronics of today, the graceful playing expressed by all means that at this early date Braxton and the others had perfected the subtle art of matching electronic and acoustic textures without conflict.

The brilliance of this CD substantiates Sackville’s vision. It also suggests that years from now the concept of Canadian labels releasing foreign-sourced experimental music will more likely be praised for foresight rather than eccentricity.

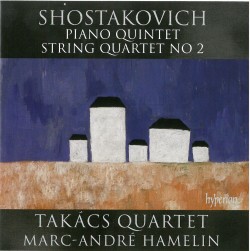

Shostakovich – Piano Quintet;

Shostakovich – Piano Quintet;