Back in my broadcasting days, I was interviewing a British journalist – this must have been 15 years ago – about the projected demise of classical music.

Back in my broadcasting days, I was interviewing a British journalist – this must have been 15 years ago – about the projected demise of classical music.

I said, as I introduced the interview, that the eradication of classical music had been confidently predicted since recording was invented in the late-19th century, but that, although the last rites had been pronounced and the funeral arrangements made, the patient stubbornly refused to die. Then, after my “hello”, he responded with words guaranteed to stop the heart of every broadcaster on earth, trust me. “I’m afraid there’s an error in your introduction.” I gulped, swore to myself, and gamely said “How so?” “Well,” he went on, “you said the demise of classical music has been predicted since the beginning of the 20th century. The first instance I could find of such a statement was 1741!” (That was the year of Messiah, by the way).

I was reminded of this exchange this August while reading accounts of the annual meeting of the International Conference of Symphony and Opera Musicians, basically an umbrella group pressing for musicians’ rights in the classical field. The usual litany of problems: funding, reduced government support, aging audiences, lack of demographic diversity, labour troubles. And to be fair, those problems are all too real. The economics of classical music, especially at the level of large organizations, are an actuarial definition of hell. Enormous fixed costs with no easy possibility of reducing them – you can’t just eliminate the second violins from a Mozart symphony. Fixed costs that are increasing. A very real limit to how far ticket prices can rise to meet those increased costs without depressing the potential number of buyers, so that higher prices, bizarrely, result in lower revenue. An art form that only finds success with an endless succession of greatest hits programs, thus reducing the ability to attract new audiences not familiar with the established repertoire. And a current audience that, barring great advances in cryogenics, will all be dead in ten years or so. How can this enterprise possibly survive?

But it does, and in some cases, even thrives. Umberto Eco, the famed Italian author, once told a Davos world economic forum audience that some things were never going to be replaced by new technology. His example? The spoon. The spoon will never disappear, he said, because nothing else does what it does as efficiently or as effectively. That’s classical music, to me – it provides an emotional, spiritual and esthetic experience that cannot be replicated, really, by anything else.

That’s not to say that classical music (such a terrible adjective, but it’s ours) is destined to live forever, without any effort taken to husband its resources carefully and provide for its future. It can die. What will keep it alive is not just great performances (although nothing can substitute for them), but a willingness even in these troubled times, I would say, especially in these troubled times, to strike out with boldness and originality in programming, repertoire and presentation to keep the art form vital.

The good news is that the audience problems that cause so many sleepless nights for so many artistic administrators may well solve themselves, as the traditional boundaries between musical genres break down. This, in fact, may well be the most significant development in music over the past 50 years. Classical players now have experience in jazz, pop performers know their opera, world music is blurring all sorts of musical lines. Contemporary musicians of all kinds are comfortable in wide areas of musical style and expertise. This is great news for the classics, because “classical” music, a minority musical niche, can only benefit from this expansion.

I said earlier that classical music was irreplaceable, but I didn’t say why. Classical music is like Umberto Eco’s spoon because it takes music seriously; it is a perfectly suited means of delving deep into music’s full range of techniques, meanings, emotion and power, rather than, as popular music does, happily skimming the surface in the worlds of entertainment and immediate pleasure – not that there is anything wrong with either of these – for the commercial rewards there. Depth doesn’t necessarily sell, but that doesn’t mean that it doesn’t attract. The fact that the classical gene – the gene for depth – is now being carried by young musicians who know their classics but are comfortable and excited by other forms of music does not mean a contraction of classical music, or a horrible death-spiral of crossover hybrids, whirring into meaninglessness and irrelevance. It means the opposite. It means that the world of classical music will be augmented by new consciousnesses, expanded to include elements of styles that already have their audiences, thereby liberating classical music from its depleting dependencies, both in terms of audience and repertoire.

That’s not to say that my ideal classical institutions wouldn’t include the classics – after all, they’re what got us here in the first place. But the classics can be presented in so many more inviting concertgoing styles than the typical symphony program set in a granite-like unalterability for over a hundred, otherwise changing, years. Nothing forbids orchestras or chamber groups from being a little more imaginative in their programming and presentation. Or even a lot more. Everybody is ready for something new – even the old-guard audiences that terrify precarious mainstream institutions into inertia. The proof of that is everywhere around us – in groups like the highly lauded Against the Grain Theatre, Opera Atelier and the new Tafelmusik, under Elisa Citterio, to name just a few. Even the Toronto Symphony, going through their own rebuild these days (a la the Blue Jays), have done well with their ventures out of the tried and true in the past few years. Many classical institutions are stuck in an artistic Stockholm syndrome, struck immobile by a fear of disturbing the delicate balance that allows them to survive. But disturb it they must – with care, certainly, and intelligence, and taste, but with courage in the end, and a belief in the value of what they have the good privilege to serve up to the world.

The listings in the magazine in your very hands at the moment –or scrollable on your screen – prove the immense ongoing interest in classical music. The precarious nature of the business has not stopped thousands of young people, if not hundreds of thousands, from entering institutions of musical learning annually, declaring their love of the art form by showing a willingness to dedicate their lives to it. Talent is not the problem in the musical world these days. New ideas are. And willingness, both by the venerable institutions that are the art form’s custodians and the audiences that have traditionally supported them, to help midwife the new world of the classics that is straining to be born.

Robert Harris is a writer and broadcaster on music in all its forms. He is the former classical music critic of the Globe and Mail and the author of the Stratford Lectures and Song of a Nation: The Untold Story of O Canada.

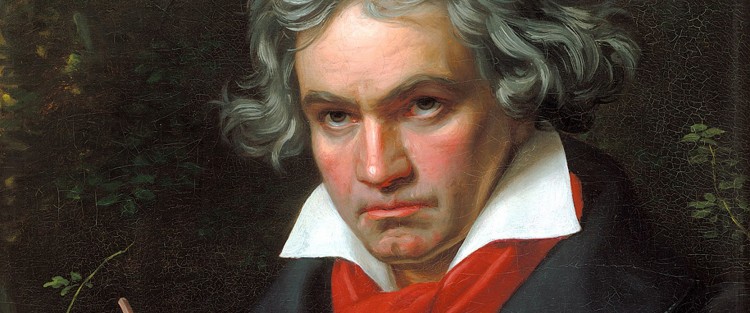

The immovable reputation of Beethoven is the kind of continuity that either confirms the unchanging greatness of classical music, or makes us despair of the depth of its conventionality and inertness. I am old enough to remember the last time the world celebrated a major Beethoven anniversary, his 200th, in 1970. Fifty years later, just about everything in the world has changed, but Beethoven, it seems, has not.

The immovable reputation of Beethoven is the kind of continuity that either confirms the unchanging greatness of classical music, or makes us despair of the depth of its conventionality and inertness. I am old enough to remember the last time the world celebrated a major Beethoven anniversary, his 200th, in 1970. Fifty years later, just about everything in the world has changed, but Beethoven, it seems, has not.

Back in my broadcasting days, I was interviewing a British journalist – this must have been 15 years ago – about the projected demise of classical music.

Back in my broadcasting days, I was interviewing a British journalist – this must have been 15 years ago – about the projected demise of classical music.