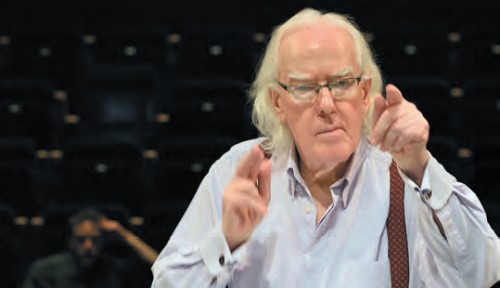

Rock and Rage: Richard Rose on Tarragon’s Hamlet

"Music Theatre” as we use the term in The WholeNote is a large tent, covering a wide range of productions and performances in which music pervades the drama rather than simply decorating it. It’s this interweaving that I will be hoping for in a new version of a Shakespearean classic opening at the Tarragon Theatre in Toronto on January 2. Artistic director Richard Rose is making a foray into new and uncharted (pun intended) territory with a rock and roll Hamlet, with music and music direction by his longtime collaborator Thomas Ryder Payne.

"Music Theatre” as we use the term in The WholeNote is a large tent, covering a wide range of productions and performances in which music pervades the drama rather than simply decorating it. It’s this interweaving that I will be hoping for in a new version of a Shakespearean classic opening at the Tarragon Theatre in Toronto on January 2. Artistic director Richard Rose is making a foray into new and uncharted (pun intended) territory with a rock and roll Hamlet, with music and music direction by his longtime collaborator Thomas Ryder Payne.

As a longtime devotee of both Shakespeare and musicals, with a particular fascination for when the two become blended into one, I contacted Rose to find out more about the inspiration behind this idea and what we might expect.

The show isn’t even in rehearsal yet, so it is early for the director to speak about what we will see in January – but in some ways it was even more interesting to have that conversation now, as the concept and its development are currently still in flux. Here is some of what we spoke about (edited for length):

WN: What was the initial inspiration to turn Hamlet into a rock and roll musical?

RR: I’ve always wanted to do Hamlet, and you want to find a great time to do it. It’s not really a rock and roll musical. It’s part concert, part radio play, part performance. I’m not sure where it will eventually land. I had an idea that it would be interesting to do Hamlet accompanied by a rock and roll concert. I didn’t really know what that would lead to except that the play always seemed to be about a young person’s despair and rage against the system, about trying to find out who they are. Hamlet is struggling between being a hero who can take action and his conscience: how do you act in the world when the world is actually politically corrupt?

But why rock and roll particularly?

Because of the rage. Marshall McLuhan talks about how young people have turned to rock and roll to push out all this information of the electronic age that is coming at them, and they’re shrieking, trying to express their identity – and that’s why it is so loud – to somehow express their anger – and that’s Hamlet, isn’t it? He is asking “Am I man of action or conscience? Can I kill someone, can I commit an act of revenge knowing that the society and the world around me is filled with lies? I have to do absolutely the right thing, but I don’t know what the right thing is.”

If we have a world full of lies it is very hard to know who we are; here the music, the rock and roll, will be a fundamental way of showing the anger at the hypocrisy of the world and it goes further than that.

You and Thomas Ryder Payne are longtime collaborators. But every show is different. How did it work this time?

He was part of the project from the beginning and we both felt that Hamlet was the right fit for a rock and roll take, and rock and roll was the way to connect to young audiences today. In a preliminary workshop a rough concept emerged, of speaking the text against a musical background. Hamlet’s soliloquies, for example, got bashed against the progression of a rock and roll guitar accompaniment [capturing] a feeling of what Hamlet is going through as he speaks. Then we started to find and develop a sonic experience.

Sonic experience?

An environmental mood creating the overall time and space of the play, as well as for specific scenes and effects such as the appearance of the ghost – or the chaos of the Danish Court through a mashup of Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture with jazz and martial music. So, while this is not at all a traditional rock musical, music is essential and dictated the working method. We would jam like a rock band: someone comes up with a riff, someone starts to work with that riff, someone starts to sing a song to that riff or we speak to that riff.

Where do the actors fit into the process?

Call it ongoing experimentation – the company is not yet officially in rehearsal at this point. It’s things like the actors taking a different approach to the text, looking at the words as song lyrics from different genres such as punk, or from the points of view of singers as different as Mick Jagger, Frank Sinatra or Peggy Lee, to see what effect this has on the speaking or thinking of the lines.

And actual songs?

There will be at least some songs as well as the underscoring and background music. Hamlet will have a song of his own, though most of the soliloquies are spoken. The Gravedigger has a song as he actually does in the play. Hamlet and Ophelia’s relationship will be explored through music with Ophelia possibly singing snatches of her later “mad songs” as happy innocent pop songs early in the play, then distorted versions of those songs after the death of her father… And we’re seeing the play within the play, when Hamlet tries to prove Claudius’ guilt, as a kind of mini-operetta, a heightened moment of performance for the other characters to watch…. Most of it though will be spoken against music rather than sung – [and while] there will be some elements of staging the performers will mostly be acting the play at microphones like a radio play, but supported by the sound behind that evokes the world, the inner life, and works with them.

And the musicians?

The actors themselves. Only two will not be singing or playing instruments: Nigel Shawn Williams as Claudius, and Tantoo Cardinal as Gertrude. All the others will be singing and playing instruments, with no additional musicians to back them up other than [composer and music director] Thomas Ryder Payne as live mixer and sound man.

As Rose went on to explain, the company is comprised of actors who are almost all musicians as well. Noah Reid, whose album Songs from a Broken Chair is available on iTunes, stars as Hamlet. Brandon McGibbon of the ElastoCitizens, and many musical theatre credits including Once and The Producers, will play Laertes as a teenager so obsessed with his guitar that he never puts it down until his world falls apart with the death of his father and madness of his sister. Jack Nicholsen, Greg Gale, Jesse LaVercombe, Beau Dixon, Cliff Saunders, Rachel Cairns (the one piece of cross-gender casting as Rosencrantz) all have strong musical backgrounds, and Tiffany Ayalik, who plays Ophelia, has special vocal techniques from the discipline of throat singing “to go to places other people don’t go.”

“To go to places other people don’t go” sounds like a fitting mission statement for this latest outing by an always adventurous theatrical team.

Hamlet runs January 2 to February 11 in the Tarragon Main Space at 30 Bridgman Ave., Toronto.