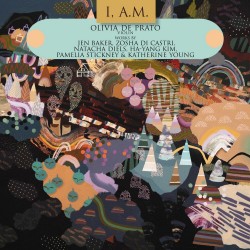

I, A.M. - Olivia De Prato

I, A.M.

I, A.M.

Olivia De Prato

New World Records (newworldrecords.org)

This insightful new release by Austro-Italian violinist extraordinaire Olivia De Prato probes a neverending question of connection between motherhood and art. The answer comes in the form of six compositions for violin, electronics and other varied instruments, written by women dedicated to both motherhood and art. Contrary to some traditional views, these women artists show not only that motherhood is an ultimate creative experience but also that it is the experience that cultivates creativity in other areas of life.

The music on this album is avant-garde, piercing and inspiring. This is the world of ideas bypassing linear melodies in favour of textural gestures and landscapes. Just like motherhood, this music stretches the sonic boundaries and continuously underlines the element of unpredictability and beauty in chaos. De Prato is superb as performer and collaborator, delving deeply into what is possible in the realms of extended violin technique and conceptual sounds.

While Katherine Young’s Mycorrhiza I builds an innovative music vocabulary using natural sounds such as heartbeat and breathing juxtaposed with bold elements of extended violin technique, Ha-Yang Kim’s May You Dream of rainbows in magical lands brings in the non-rhythmical layers of long violin tones using a just intonation system called Centaur. Pamela Stickney’s noch unbenannt features heavenly sounds of the theremin, both merged and intercepted by an array of textures produced on the violin, referencing an attempt to put a baby to sleep.

These compositions are undaunted creations of strong women artists in an ever-changing world.