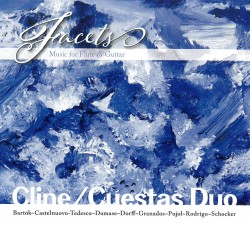

Facets - Cline/Cuestas Duo

Facets

Facets

Cline/Cuestas Duo

Independent (clinecuestasduo.com)

There are many fine flutists in the world these days, and Jenny Cline of the Cline/Cuestas Duo is definitely one of them. She and guitarist Carlos Cuestas have put together a terrific program which combines four substantial contemporary compositions balanced by music from the late 19th and the early- and the mid-20th centuries.

At 15 minutes, Maximo Diego Pujol’s Suite Buenos Aires is the longest of the four contemporary pieces. Composed in 1995, its four movements depict different parts of the city after which it is named. The slow second movement is particularly exquisite, opening with a guitar solo beautifully played by Cuestas, setting up Cline for the heartrending solo which follows. The last movement too, is particularly noteworthy, bristling with excitement and precise teamwork.

Among the earlier compositions are six of Bartók’s Romanian Dances and Enrique Granados’ Danza Española No. 5: Andaluza, from which the duo draws haunting nostalgia for times past in pre-cataclysm Eastern Europe and Spain respectively.

Daniel Dorff’s Serenade to Eve, After Rodin (1999), beginning passionately lyrical and moving to an astonishing virtuosic conclusion, is yet another great addition to the contemporary repertoire for flute and guitar. So too is Gary Schocker’s Silk Worms, music of great refinement commissioned by the duo in 2013 and interpreted here with warmth and conviction.

Credit also goes to Oscar Zambrano, who mastered the recording, for really getting the balance between the two instruments just right. Congratulations to all who were involved for an excellent first CD.