It’s been a simply terrific month for cello discs.

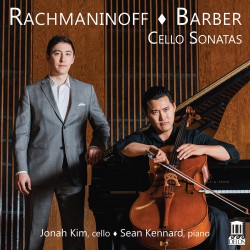

Cellist Jonah Kim and pianist Sean Kennard were together as teenagers at the Curtis Institute and again at Juilliard. For Rachmaninoff and Barber Cello Sonatas, their first album on the Delos label, they have chosen Rachmaninoff’s Cello Sonata Op.19 and Samuel Barber’s Cello Sonata Op.6 (Delos DE 3574 naxosdirect.com/search/de+3574).

Cellist Jonah Kim and pianist Sean Kennard were together as teenagers at the Curtis Institute and again at Juilliard. For Rachmaninoff and Barber Cello Sonatas, their first album on the Delos label, they have chosen Rachmaninoff’s Cello Sonata Op.19 and Samuel Barber’s Cello Sonata Op.6 (Delos DE 3574 naxosdirect.com/search/de+3574).

The composers were both in their 20s when writing the works, and heart-on-sleeve romanticism and expansive melodies are common to both sonatas. Despite the balanced writing in the Rachmaninoff, there’s a notoriously difficult piano part which Kennard handles superbly.

There’s a deeply personal link to the Barber sonata here. Barber himself studied at the Curtis Institute and wrote his sonata there in 1932 with help from cellist and fellow student Orlando Cole, who premiered the work with Barber in 1933. Cole, who died in 2010 at 101, taught at Curtis for 75 years and counted Johan Kim among his students; Kim and Kennard received priceless coaching from Cole in their performance of the work.

There’s an abundance of lovely playing here, with a beautiful cello tone and a rich and sonorous piano sound perfectly suited to the flowing melodic lines that are central to these strongly Romantic works.

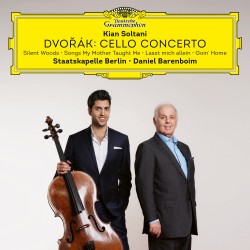

Kian Soltani is the soloist in the Dvořák Cello Concerto with Daniel Barenboim conducting the Staatskapelle Berlin in a performance recorded live in concert at the Berlin Philharmonie in October 2018 (Deutsche Grammophon 00028948360901 kiansoltani.com/discography).

Kian Soltani is the soloist in the Dvořák Cello Concerto with Daniel Barenboim conducting the Staatskapelle Berlin in a performance recorded live in concert at the Berlin Philharmonie in October 2018 (Deutsche Grammophon 00028948360901 kiansoltani.com/discography).

Barenboim has been general music director of the orchestra since 1992, and the lengthy but lovely orchestral start to the concerto is a reminder of just how much of a master he is on the podium. He also has a personal connection with Soltani, having worked on the concerto with the cellist in 2014 prior to Soltani’s first concert performance of the work. Soltani plays the London ex-Boccherini Stradivarius cello on loan, and what a tone he produces! It’s a simply superb performance in all respects.

Five short Dvořák pieces arranged for solo cello and cello ensemble of six players – three of the arrangements by Soltani – complete the disc: Lasst mich allein (the song that has such emotional significance in the concerto); Goin’ Home (after the Largo from the New World Symphony); Songs My Mother Taught Me (from Gypsy Melodies Op.55); Allegro moderato (from Four Romantic Pieces Op.75); and Silent Woods (from From the Bohemian Forest Op.68).

The live performance of the concerto has richness, immediacy, depth, emotional commitment and tension and a great sound. Stay for the ensemble arrangements, but buy this CD for the concerto.

The outstanding cellist Alban Gerhardt is back with more stellar performances on Shostakovich Cello Concertos, with the WDR Sinfonieorchester under Jukka-Pekka Saraste (Hyperion CDA68340 hyperion-records.co.uk).

The outstanding cellist Alban Gerhardt is back with more stellar performances on Shostakovich Cello Concertos, with the WDR Sinfonieorchester under Jukka-Pekka Saraste (Hyperion CDA68340 hyperion-records.co.uk).

Both works were written for the Russian cellist Mstislav Rostropovich, and despite Gerhardt’s admitted “utter adoration” for Rostropovich and an awareness of his relationship with the composer, he admits that he has ignored his interpretations, essentially because Shostakovich’s markings in both concertos were largely ignored by the Russian cellist.

The Concerto No.1 in E-flat Major Op.107 from 1959 has four movements, the third being a towering solo cello cadenza almost six minutes in length that perfectly frames Gerhardt’s technical and interpretational abilities.

The Concerto No.2 in G Major Op.126 from 1966 began as a memorial piece for the poetess Anna Akhmatova, who had died earlier in the year. An essentially reflective work, Rostropovich considered it the greatest of the numerous concertos written for him.

Terrific performances of two of the great 20th-century cello concertos make for an outstanding CD.

There’s a very clear message in the programing of Voice of Hope, the new CD from the Franco-Belgian cellist Camille Thomas with the Brussels Philharmonic (Deutsche Grammophon 00028948385645 camillethomas.com/VoiceOfHope.php). Building a selection of songs, prayers and laments around the world premiere recording of the Cello Concerto “Never Give Up” Op.73 by the Turkish composer Fazil Say, it pays tribute “to people’s ability to triumph over adversity, create harmony in place of chaos, and overcome hatred with love.”

There’s a very clear message in the programing of Voice of Hope, the new CD from the Franco-Belgian cellist Camille Thomas with the Brussels Philharmonic (Deutsche Grammophon 00028948385645 camillethomas.com/VoiceOfHope.php). Building a selection of songs, prayers and laments around the world premiere recording of the Cello Concerto “Never Give Up” Op.73 by the Turkish composer Fazil Say, it pays tribute “to people’s ability to triumph over adversity, create harmony in place of chaos, and overcome hatred with love.”

Say’s three-movement concerto, a vivid, emotional and quite unsettling but extremely effective response to terrorist attacks in Istanbul and Paris, was written for and premiered by Thomas. It is performed here on the 1730 Stradivarius cello once owned by Emanuel Feuermann, with the orchestra’s music director Stéphane Denève as conductor. The remaining tracks are conducted by Mathieu Herzog, who also made several of the numerous arrangements, only Bruch’s Kol Nidrei appearing in its original form.

Also included are Ravel’s Kaddisch, Dvořák’s Songs My Mother Taught Me, John Williams’ Theme from Schindler’s List, Wagner’s Träume from the Wesendonck-Lieder, Gluck’s Dance of the Blessed Spirits and well-known arias from the operas Dido and Aeneas, L’elisir d’amore, Norma, Werther, Don Giovanni and Nabucco.

Thomas says that she “wanted to choose works that represented this idea that beauty will save the world, quite simply.” Quite simply, there’s certainly beauty in her playing.

The American harpist and organist Parker Ramsay has a master’s degree in harp performance from Juilliard, and is equally at home on modern and period instruments. Bach Goldberg Variations is his first solo harp recording, and it’s a remarkable accomplishment (King’s College Recordings parkerramsay.com).

The American harpist and organist Parker Ramsay has a master’s degree in harp performance from Juilliard, and is equally at home on modern and period instruments. Bach Goldberg Variations is his first solo harp recording, and it’s a remarkable accomplishment (King’s College Recordings parkerramsay.com).

Apparently the Goldberg Variations can only be played on the harp in G major, which luckily happens to be Bach’s key. A keyboard/harp comparison reveals interesting differences: difficult keyboard flourishes are often easier on the harp, while simple keyboard linear melodies are more difficult or even impossible, especially if rapid pedal changes are needed for chromatic passages. The modern pedal harp, though, offered Ramsay what he terms “the best of both worlds: it’s a plucked instrument like the harpsichord, but is sensitive to pressure, like the piano.”

Listening to this CD the first thing that strikes you is the astonishing articulation – the accuracy, fluency and agility, especially in the ornamentation and in the faster, more florid variations. With the harp’s added resonance Ramsay stresses the opportunity to present the harmonic structures as well as the contrapuntal in what is a gentle and atmospheric sound world.

In a recent New York Times article Ramsay says that he realized that “the way to hear this work – and most of Bach, for that matter – as I wanted would be to use my first instrument, the modern pedal harp.” On this remarkable and immensely intriguing and satisfying showing, it’s hard to disagree with him.

There’s more Bach music in transcription on Volume One of Johann Sebastian Bach Cello Suites arranged for guitar (Naxos 8.573625 naxosdirect.com/search/747313362578) by Jeffrey McFadden, the outstanding Canadian guitarist who is Chair of Guitar Studies at the University of Toronto, and whose debut recording in the early 1990s was the first CD in the prestigious Naxos Guitar Laureate Series.

There’s more Bach music in transcription on Volume One of Johann Sebastian Bach Cello Suites arranged for guitar (Naxos 8.573625 naxosdirect.com/search/747313362578) by Jeffrey McFadden, the outstanding Canadian guitarist who is Chair of Guitar Studies at the University of Toronto, and whose debut recording in the early 1990s was the first CD in the prestigious Naxos Guitar Laureate Series.

It’s not unusual for recorded works to take a year or two to reach CD release, but both the McFadden arrangements (which remain unpublished) and the recording here were made in 2009. Still, there’s no doubting the quality and effectiveness of both the arrangements and the performance of the three Suites No.1 in G Major BWV1007, No.2 in D Minor BWV1008 and No.3 in C Major BWV1009. Recorded at St. John Chrysostom Church in Newmarket by the always-reliable Norbert Kraft (with whom McFadden studied) the sound quality on a charming disc is, as usual, exemplary.

Volume Two is apparently scheduled for release this month.

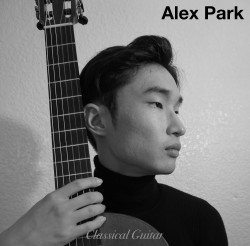

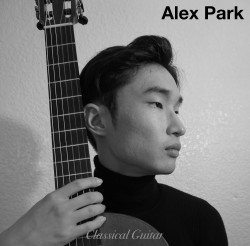

There certainly seems to be no shortage of outstanding young guitarists these days. Classical Guitar is the debut release from guitarist Alex Park, and offers exemplary performances of a range of short pieces both familiar and unfamiliar (alexparkguitar.com).

There certainly seems to be no shortage of outstanding young guitarists these days. Classical Guitar is the debut release from guitarist Alex Park, and offers exemplary performances of a range of short pieces both familiar and unfamiliar (alexparkguitar.com).

The Gigue from Ponce’s Suite in A Minor provides a bright and brilliant opening to a recital that ranges from Conde Claros by the 16th-century Spanish composer Luis de Narváez and John Dowland’s Allemande (My Lady Hunsdon’s Puffe) through Handel’s Sarabande & Variations and Debussy’s The Girl with the Flaxen Hair to the traditional Irish tune Spatter the Dew.

Four standard classical guitar pieces – three of which display Park’s dazzling tremolo technique – complete the disc: Tarrega’s Recuerdos de la Alhambra; Albéniz’s Leyenda; Villa-Lobos’ Prelude No.2 (given a performance more fluid than many); and Agustín Barrios’ Una Limosna por el Amor de Dios.

The publicity blurb for the CD release noted that Park has “a superb sense of dynamics, tempo and phrasing, performing with deep expression.” Add terrific technical assurance and you have a pretty good description of the playing here.

The Russian duo of violinist Anna Ovsyanikova and pianist Julia Sinani is in top form on Les Saisons Françaises, a quite delightful recital disc of late 18th- and early 19th-century French music by Debussy, Lili Boulanger, Ravel and Poulenc (Stone Records 50601927780963 stonerecords.co.uk).

The Russian duo of violinist Anna Ovsyanikova and pianist Julia Sinani is in top form on Les Saisons Françaises, a quite delightful recital disc of late 18th- and early 19th-century French music by Debussy, Lili Boulanger, Ravel and Poulenc (Stone Records 50601927780963 stonerecords.co.uk).

There’s warmth and a lustrous violin tone in the 1917 Debussy Violin Sonata in G Minor and a beautifully clear and bright performance of Boulanger’s Deux Morceaux – Nocturne and Cortège. Two works that are less often heard are the real gems here though: Ravel’s single-movement Sonata for Violin and Piano No.1 “Posthume” and Poulenc’s three-movement Sonata for Violin and Piano.

The Ravel work was written in 1897 while the composer was still a student but wasn’t published until 1975, almost 40 years after his death. It’s a really lovely piece that combines Romantic and Impressionistic styles and moods.

Poulenc apparently destroyed several earlier attempts at a violin sonata, his only surviving work in the genre being the sonata composed in 1942-43 at the request of, and with the help of, Ginette Neveu. Following Neveu’s tragic death at the age of 30 in a 1949 plane crash, Poulenc revised the finale, reducing the length and reworking the violin part. Both versions of the movement are included here.

The composer himself was disparaging about the work – it is ”alas not the best Poulenc,” he said, and “Poulenc is no longer quite Poulenc when he writes for the violin” – but at this remove it seems a gorgeous and quite idiomatic work. Given performances like this it makes you wonder why it isn’t firmly established in the standard repertoire.

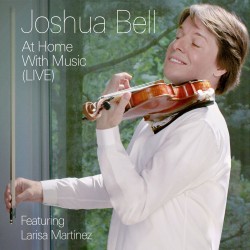

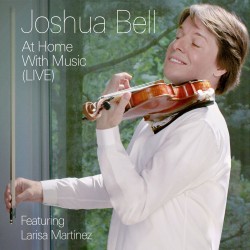

The CD Joshua Bell: At Home With Music (LIVE) presents eight performances from the PBS-TV special Joshua Bell: Live At Home With Music broadcast on August 16. Described as “A musical soirée of intimate performances from home, while sharing a behind-the-scenes look at family, Bell’s own musical inspirations, and more,” the CD features the soprano Larisa Martínez (Bell’s wife) and pianists Peter Dugan, Kamal Kahn and Jeremy Denk (Sony Classical 886448695332 joshuabell.com/#recordings).

The CD Joshua Bell: At Home With Music (LIVE) presents eight performances from the PBS-TV special Joshua Bell: Live At Home With Music broadcast on August 16. Described as “A musical soirée of intimate performances from home, while sharing a behind-the-scenes look at family, Bell’s own musical inspirations, and more,” the CD features the soprano Larisa Martínez (Bell’s wife) and pianists Peter Dugan, Kamal Kahn and Jeremy Denk (Sony Classical 886448695332 joshuabell.com/#recordings).

The first movement of Beethoven’s Spring Sonata provides a lovely opening to a program that includes Kreisler’s arrangement of Dvořák’s Slavonic Fantasy in B Minor, Wieniawski’s Polonaise de Concert in D Major Op.4, Chopin’s Nocturne in E-flat Major Op.9 No.2 and Heifetz’s arrangement of Summertime from Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess.

Martínez is the vocalist in Ah, ritorna, età dell’oro from Mendelssohn’s Infelice, Quando m’en vo from Puccini’s La Bohème and a Medley from Bernstein and Sondheim’s West Side Story.

Playing the 1713 Huberman Stradivarius with an 18th-century bow by François Tourte, Bell exhibits a full-blooded, all-in approach that doesn’t for a moment imply any lack of subtlety or nuance. It’s simply captivating playing.

Schubert – Octet

Schubert – Octet