Ann Southam

SCHOENBERG ONCE SAID there was great music still to be written in C. Ann Southam proved him right. As she said of some of her pieces, they “cheerfully hunted for Middle C”– and in doing so had a disconcerting way of reinterpreting familiar forms and techniques.

SCHOENBERG ONCE SAID there was great music still to be written in C. Ann Southam proved him right. As she said of some of her pieces, they “cheerfully hunted for Middle C”– and in doing so had a disconcerting way of reinterpreting familiar forms and techniques.

A graduate of the University of Toronto and the Royal Conservatory of Music, Ann wrote music in a wide range of styles. Her lyricism and fascination with an instrument’s body, resonance, tone and sensuality re-invented the art. Although she continued to use a 12 tone row and spin it out, one note at a time for 20 years, Ann hoped she could bring some tonal sense to the serial technique. It may be called “minimal,” but her works embroider the layers of tonal fabric created through the serial row – weaving in a manner that reflects traditional women’s work.

Starting off as one of Canada’s pioneers in electronic music, Ann created her early work for dancers. She loved working with them, and felt that because they could sense the time space as much as the physical space, she didn’t have to write anything down. She just created her music directly.

When she wrote for piano, she continued to work directly on the instrument, as she did in composing her series of solo piano pieces, Rivers. “After the exotic and ‘disembodied’ world of electroacoustic music in which I’d worked for many years,” she said, “there was the sheer pleasure of making music by hand – the pleasure of touch.”

Some of Ann’s major piano compositions include works in the virtuosic tradition of Chopin and Liszt. Her pieces are characterized by a flow and energy produced by rhythmic cycles that repeat within interchanging melodic motifs. Her slow music suspends our sense of time, while the fast pieces, with their undercurrent of recklessness, become hypnotic and surprisingly tranquil and reflective. Although maintaining an angular tone row, both extremes reveal a serene lyricism that is a common thread in her music.

A generous philanthropist and strong advocate of Canadian women artists, Ann also mentored young composers and was always eager to learn about their music. One young composer, who is completing his doctorate at the University of Toronto, was surprised when Southam came to his concert last year. She said that she no longer wanted to talk about her work. She was more fascinated with how their encounters influenced his music.

Ann was also a fun-loving woman who loved east coast fiddle music and bagpipes. She was without pretence or artistic snobbery and could see humour in any situation. While we were working on a recording project, Ann was sitting on my floor with her manuscript laid out in front of her. One of my dogs, a puppy at the time, bolted from the kitchen and headed straight for Ann, but seeing the paper on the floor did what puppies are expected to do. I was horrified. As we ran to the bathroom with the dripping manuscript, Ann turned to me and remarked, “I hope that wasn’t a comment on my music!” Her irrepressible sense of humour is one of the qualities that made her a joy to work with.

Ann Southam will be remembered for her unique voice and individual style in musical compositions that allowed interpreters and dancers the freedom and flexibility for their own creativity to flourish. Her collaborators, who included the best artists, dancers, choreographers and musicians in Canada, are feeling her loss with immense sadness and remembering her with admiration and gratitude for the legacy she left.

Her generosity of spirit and her music will stay with us forever.

Christina Petrowska Quilico is professor, piano and musicology, and director of classical piano in the Department of Music, York University.

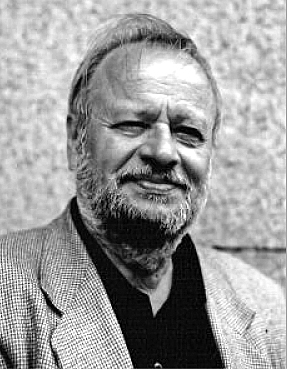

ANTONÍN KUBÁLEK WAS A GREAT AND GOOD MAN whom I had the honour of knowing for some 30 years. Always quick with a smile, a joke, and a drink, Anton reveled in the absurd. Life never failed to supply him with suitable material, even in his childhood. He attended a school for the blind following an accident with a post-war bazooka, though he eventually regained partial site in his remaining eye. As as a citizen of a Socialist paradise however he was required to wear a bag over his head in the classroom so that his comrades should not feel disadvantaged! Later, as a rising young pianist, he would be sent out on tours by the Czech concert bureau, arriving at back-water recital halls to wrestle with ill-tuned instruments with missing keys and even legs and, on one memorable occasion, finding an accordion laid out for him. He knew from experience to always have a packed bag ready, so that when Prague seethed in turmoil in 1968 he was well-prepared to flee to Vienna. There, at the Canadian Embassy, he was shown a map and chose a city called Toronto, because he was impressed by the size of its lake.

ANTONÍN KUBÁLEK WAS A GREAT AND GOOD MAN whom I had the honour of knowing for some 30 years. Always quick with a smile, a joke, and a drink, Anton reveled in the absurd. Life never failed to supply him with suitable material, even in his childhood. He attended a school for the blind following an accident with a post-war bazooka, though he eventually regained partial site in his remaining eye. As as a citizen of a Socialist paradise however he was required to wear a bag over his head in the classroom so that his comrades should not feel disadvantaged! Later, as a rising young pianist, he would be sent out on tours by the Czech concert bureau, arriving at back-water recital halls to wrestle with ill-tuned instruments with missing keys and even legs and, on one memorable occasion, finding an accordion laid out for him. He knew from experience to always have a packed bag ready, so that when Prague seethed in turmoil in 1968 he was well-prepared to flee to Vienna. There, at the Canadian Embassy, he was shown a map and chose a city called Toronto, because he was impressed by the size of its lake.