Violinist Susanna McCleary shimmers in a silver top as she strides over the Miles Nadal Jewish Community Centre stage, one hand balanced lightly on the back of her mother, Dorothy de Val. McCleary leads the pair in a rousing rendition of the klezmer piece Hora Marasinei, her brow furrowed in concentration as her bow darts and dances over her violin. De Val replicates her rhythms on the piano, and mother and daughter sway in synchrony.

Violinist Susanna McCleary shimmers in a silver top as she strides over the Miles Nadal Jewish Community Centre stage, one hand balanced lightly on the back of her mother, Dorothy de Val. McCleary leads the pair in a rousing rendition of the klezmer piece Hora Marasinei, her brow furrowed in concentration as her bow darts and dances over her violin. De Val replicates her rhythms on the piano, and mother and daughter sway in synchrony.

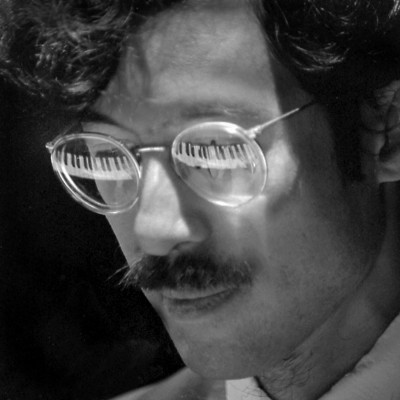

After their opening act, pianist Michael Arnowitt grabs his white cane and heads into the spotlight. As his nimble fingers plunge into a series of Bach selections, Arnowitt is mesmerized by the music, punctuating the accents with sharp tosses of his head. The final, plaintive note quivers for an eternity in the hush of the room.

This performance on October 15 last year, “An Evening in the Key of B: A Benefit Concert,” was a fundraiser for the non-profit organization BALANCE for Blind Adults (balancefba.org), which helps visually impaired clients regain their independence.

The two musicians resonate with the relevance of this mission – both are blind, and both have had to overcome challenges springing from this state. But their loss of eyesight has also garnered them gifts, sharpening their other senses to make up for this deficit. And these finely tuned faculties of hearing and touch have, in turn, moulded their artistry.

McCleary and Arnowitt join the ranks of a long line of blind and brilliant musicians, including soul music pioneer Ray Charles, rocker Stevie Wonder and opera singer Andrea Bocelli. The sheer number of such performers has long caused music connoisseurs to wonder if there is a special relationship between vision loss and musicality.

This affiliation has now been thoroughly documented. One of the first researchers to link the two qualities was Adam Ockelford, professor of music at England’s Roehampton University. Ockelford found that an astonishing 40 percent of the blind children in his studies had perfect pitch, (compared to only one in 10,000 people in the regular population). This capacity springs from the youngsters’ lifelong reliance on auditory data to make sense of their world, says Ockelford. Right from birth, the blind children paid more attention to everyday noises than their sighted peers, and their attunement to aural input reinforced their sensitivity to sound.

This affiliation has now been thoroughly documented. One of the first researchers to link the two qualities was Adam Ockelford, professor of music at England’s Roehampton University. Ockelford found that an astonishing 40 percent of the blind children in his studies had perfect pitch, (compared to only one in 10,000 people in the regular population). This capacity springs from the youngsters’ lifelong reliance on auditory data to make sense of their world, says Ockelford. Right from birth, the blind children paid more attention to everyday noises than their sighted peers, and their attunement to aural input reinforced their sensitivity to sound.

Ockelford’s theory of brain adaptation has been validated by a host of evidence. The hearing of blind people surpasses that of the sighted in in several modalities – they are better at discriminating between different pitches, localizing sounds in space, and processing speech. Their sense of touch is also more refined and they’re able to detect finer-grained differences in the feel of objects.

The brain’s ability to compensate for visual loss with enhanced perception in other domains, is adaptive, says McGill University’s research associate Patrice Voss. If you’re born without vision, or you lose it early in life (when the brain is especially mouldable), the sight-processing centre in the brain (the visual cortex), does not receive input from the eyes. In response to these absent signals, the unused visual cortex gets repurposed to process sound and touch stimuli instead.

Anatomical changes accompany this transformation. Imaging studies have shown that the visual cortex is thicker than normal among those who become blind early in life. This growth results from new pathways springing from the sound and touch processing centres, connecting these to the transformed visual cortex, reorganized to interpret signals from the ears and skin.

While amplified sound sensitivity is more prominent amongst those who are born blind or lose their sight early on, recent research shows that the brain can adjust to vision loss at any stage in life. In one study, mice were blinded temporarily after being shut in the dark. Afterwards, researchers played tones of varying frequencies and measured the electrical activity of cells in their brains’ sound processing centre (auditory cortex). After just one week of light deprivation, these cells fired faster and more powerfully, enabling the blind mice to detect quieter noises and distinguish between pitches much better than the sighted mice.

Lead researcher Hey-Kyoung Lee, professor of neuroscience at Baltimore’s Johns Hopkins University, attributes these impressive results to strengthened connections between nerve cells carrying sound data from the environment and those neurons which translate the signals into conscious sound experience in the auditory cortex. These alterations dial up the volume of external sound to increase its impact in the brain, says Lee, who was surprised by the extent of the animals’ adaptation. “We didn’t expect that level of change…(it) was pretty amazing.”

Violinist McCleary illustrates this plasticity of perception. She was born with Leber’s congenital amaurosis, which damages the light-sensing tissue in the eyes (the retina). But the fiddler makes up in her hearing what she lacks in vision. She can detect noises at lower volumes than her sighted friends. “If someone’s phone’s going off I can hear that better than anyone else,” she says. McCleary also has perfect pitch, which enables her to transform everyday noises, from a beeping microwave to a fork hitting the table, into musical notes.

Those without sight depend on their acoustic acumen for survival, says Voss. Their supranormal ability to map space using sound helps them get around. “They can’t rely on sight to cross the street, and need to (depend) ... on hearing to recognize where traffic is,” he says.

The same faculty is also critical for conversing, says registered psychotherapist and neurologic music therapist Amy Di Nino, who runs her own business, ADD Music Wellness (addmusicwellness.com), in Cambridge, Ontario. The timbre of a particular voice identifies the speaker, while qualities such as tone, rhythm, and pitch convey nuances of meaning. In the absence of visual cues like body language, the blind draw on their listening skills to intuit emotions in others – a rapid pace of speech can signal anxiety, while loudness can convey anger, for example.

McCleary has always depended on her heightened hearing to make sense of her world. The sound of a television in a familiar house guides her to the living room, while a squeaky noise signals the washroom door in her home. She’s also adept at extracting information from voices, and readily picks up on her mother’s feelings. “If she freaks out about something…she changes to a high voice,” says her daughter.

McCleary’s exceptional ear ultimately led to her career as a violinist. The musician showed an affinity for tunes right from infancy. “(Music) was a way in,” says her mother, a pianist and music professor, who calmed her daughter with soothing Renaissance polyphony. “She was attentive, she wouldn’t fuss or cry when music was going on.”

For as far back as she can remember, McCleary yearned to play an instrument. But teachers at her school for the blind in England, who favoured the partially sighted students, underestimated her talent and discouraged her from learning the violin. “(They) … didn’t think I could do anything,” says McCleary.

But this injustice only made her try harder. “They had a false view of me – I (was) forced to prove (them) wrong,” says McCleary. Her mother ignored the staff’s pessimism and found a private music teacher who taught her daughter the Suzuki method of learning by ear. Buoyed by his encouragement, McCleary logged up to four hours of practice a day, progressing rapidly and making her debut at church when she was only 11. Her auditory acuity helped her internalize different rhythms and master diverse musical styles, including classical violin, traditional fiddling, klezmer and Celtic. After earning a bachelor’s degree in music from McMaster University, she began performing regularly at family events, nursing homes and English country dances.

McCleary’s determination is typical of those who lose their vision early in life, says Di Nino, who has taught at the W. Ross Macdonald School for the Blind in Brantford, Ontario. These students are pros at tackling obstacles. “(When) you’re in a sighted world and you’re not visual, almost everything you do is a bit of a challenge,” she says. Di Nino has witnessed an extraordinary drive amongst her pupils, which has propelled them past hurdles. “Constantly needing to be on top of your game…create(s) a strong resilience,” says Di Nino. This toughness is a useful asset for aspiring musicians facing relentless competition and critique.

McCleary’s investment in music has paid off both personally and professionally. Because of her visual impairment, she has few distractions to enjoy during her down time, and feels at loose ends when she has nothing concrete on her agenda. Music fills the gaps during these moments. “It...gets the day going, (and) makes the time go fast,” says McCleary.

Music also gives her solace. During tough times McCleary turns to her violin for comfort. “It … helps to relieve the stress,” she says. Practising and performing with her mother is also rewarding. “When we play together, and it goes well, it makes me feel good,” says McCleary.

Like McCleary, pianist Michael Arnowitt has also battled vision loss and benefitted from it. He was born with retinitis pigmentosa, a condition which causes cells in the retina to degenerate gradually. Endowed with perfect pitch and brought up in a home filled with music, Arnowitt naturally gravitated to the medium. He astonished his first piano teacher at their initial encounter, when the five-year-old boy ploughed through an entire volume of pieces at one go. “It was some sign of prodigy talent,” he says.

He was hooked from that moment on, developing an almost mystical convergence between himself and his chosen instrument. “There’s this magical, quicker connection …the thought can become a sound,” he says. His sound was praised by critics ever since his debut as a solo pianist at age 12. Later, his gift won him a seat at the prestigious Juilliard School in New York City. But Arnowitt was ill at ease in the fast pace and competitive atmosphere of NYC and relocated to the bucolic rural town of Montpelier in his early 20s. “Vermont gave a lot of freedom to create musical events and musical styles … without … the New York Times to say ‘You suck,’” says Arnowitt. He began collaborating with a variety of artists, developing multimedia shows combining piano music with spoken commentary, live painting and even food.

Just as Arnowitt’s creativity and career were taking off, his failing eyesight forced him to make adjustments. When night blindness obscured the backstage area, Arnowitt positioned stagehands in the wings to guide him back there at the end of his concerts. Then his narrowing tunnel vision compromised his reading ability and he had to magnify his sheet music and increase the illumination onstage to enable him to play. After his vision closed off entirely a decade ago, he turned to a computer program to articulate new pieces. Playing one note at a time, the system tells you its placement in the measure, pitch, length, etc. While Arnowitt is grateful for the software, which allows him to keep learning, he’s frustrated by the tediousness of the process – it can take an hour to go through just seven bars. As well, the loss of his once dazzling sight-reading skills precludes him from jamming with others unless he’s already memorized the music. “I can’t just get together with an oboist and play for fun,” says Arnowitt.

Losing vision later in life is more challenging than being born blind, says Di Nino. As your sight gradually diminishes, you realize how much you rely on that faculty just to get around, and, in its absence, you might be limited in what you used to be able to accomplish. “You can have the feeling…(that the) world is literally closing in,” she says.

Losing vision later in life is more challenging than being born blind, says Di Nino. As your sight gradually diminishes, you realize how much you rely on that faculty just to get around, and, in its absence, you might be limited in what you used to be able to accomplish. “You can have the feeling…(that the) world is literally closing in,” she says.

Loss of sight can impact your social life as well. People usually gravitate to communities of friends who share similar capacities, so the shift into blindness can make the person feel out of place amongst their old networks. It can also shake up romantic relationships, says Di Nino.

Music therapy can be healing in these situations. As a nonverbal medium, it helps clients process their grief before they’re able to attach words to their feelings. Later, when their mobility has been restored, clients can turn to songs to help them forge connections and keep loneliness at bay. “Music is a social act to be shared,” she says.

Music therapy can also help newly blind clients augment their remaining sensory capacities and regain their functional independence. Neurologic music therapist John Hartman, from the Milwaukee Center for Independence in Wisconsin, uses musical techniques to boost auditory discrimination. In one exercise, clients try to emulate the pace and volume of the therapist’s playing, reproducing these on their own instruments. In another lesson, they concentrate on the location of sounds, turning their heads towards notes issuing from instruments spread out in the room.

Hartman also uses music to activate newly blind clients fearful of flailing around in the dark. Rhythm engages the brain’s motor area, rousing people into motion. Hartman plays clients well-known action songs like Row, row, row your boat, which stimulate movements in response to the musical cues. As clients begin to explore their surroundings in the safety of familiar pieces, their ability to navigate improves.

Arnowitt hasn’t needed formal music therapy to compensate for his perceptual loss, since he’s accomplished this naturally. Though the pianist’s hearing hasn’t changed since he lost his vision, (he already had a highly trained ear by that time), he’s become better at orienting himself in the environment. Arnowitt maintains the same organization of objects in every room, so when he looks for something, his hand always moves to the same spot. He believes this emphasis on spatial memory has impacted his piano playing. “The blindness might have caused me to be more aware of the distances between things, …so maybe I’m able to play greater jumps…on the piano,” he says.

Arnowitt’s tactile ability has also grown since he lost his vision. He attributes this development to his increased reliance on the sense to identify commonly used items like toothpaste, scissors, or a hairbrush. This experience has, in turn, refined this dimension of perception. (That)…sensitivity in the fingertips…would make (your) piano touch a little bit better,” says Arnowitt.

Music has also helped Arnowitt come to terms with the difficulties issuing from his disability. “(Music) is a peaceful escape from the world and the frustrations…the blindness creates,” he says. His years of solo practice have also made him comfortable spending long hours by himself. He rarely feels alone when he’s at the piano, since the instrument itself is a companion. So are the composers. “You have a connection to them even though you didn’t live (during) their time,” he says.

Back at the Miles Nadal Jewish Community Centre, “Evening in the Key of B” is ending. Arnowitt stands and bows. The theatre explodes with applause and cries of “Whoo, whoo.”

McCleary is relaxed after the show, her seriousness giving way to a smile as she talks to her parents. “It was a fantastic evening,” says her father. De Val agrees. “Working with Susanna is a real trip for me…she’s so professional, so musical,” she says. “It’s a bit of a high.”

Arnowitt too is surrounded by fans. These moments of communion insulate him from the loneliness that can trouble others with visual impairment. “I lead an unusual life compared to typical blind people…every time I perform, I’m surrounded by people afterwards who want to talk to me and shower me with compliments,” he says.

Every once in a while, spectators go deeper. One time a woman credited his concert with helping her mourn a death. Times like these confirm Arnowitt’s own conviction of music’s transformative potential.

“You like to think that making music is more than entertainment,” says Arnowitt. “When you know someone in the audience had a deeper experience, it gives myself, as a performer, a special satisfaction.”

Vivien Fellegi is a former family physician now working as a freelance medical journalist.